Proverbs 9:1—6

Psalm 34

Ephesians 5:15—20

John 6:51—58

The Christian worldview brings with it certain startling claims about what it means to know something, and what it means for something to be “true.” In one his Wednesday audiences, Pope Francis made this curious remark: “The truth is not grasped as a thing, the truth is encountered. It is not a possession, it is an encounter with a Person” (15 May 2013). It is curious because it stretches the boundaries of the concept of “truth” as it usually functions in common speech. How can truth be a person, except in some highly metaphorical sense? Yet the claim that “truth is a person” is not some poetic afterthought to the gospel; indeed, it comes directly from the mouth of the Lord himself: “I am the way, the truth and the life” (John 14:6). So unless John is also being highly non-literal here, Christians are committed to the claim that “truth is a Person” in a fairly straightforward sense.

At the same time, however, the affirmation that “truth is a Person” does not leave the concepts of “truth” or “person” unchanged. If indeed a relation of equivalence obtains between the two categories, then there is some sense in which all truth is “personal,” in so far as there is a personal reality coextensive with whatever may be called “true.” In other words, personhood is not a particular entity upon the ontological “field” of what is true, but rather includes and exhausts that field within itself. To seek truth is therefore to seek something that is irreducibly personal, a Person (or communion of Persons) within which all that is true “lives, moves and has its being” (Acts 17:28).

When Moses asks the Lord to reveal to him His name, so that he could tell the Israelites who sent him, he is seeking to establish and communicate the truth about something. “What is in fact the case regarding the particular identity of this divine being speaking to me” might be a way to render the question in Moses’ mind. There were lots of gods back then after all, even in the minds of the Israelites, and Moses merely wants to distinguish this (true) one from all the others. Yet the Lord’s answer is not to give a name that could be placed upon or within the ontological field of truth; it is not a description or designation of a particular entity in the world that could then be determined to exist or not exist, or to exist in this way rather than that way. No, God’s name is “I am,” which itself implies this curious notion that truth is a Person: God does not say his name is “to be” or “existence itself” but rather I am. There is no abstracting from the first-person perspective here; He who created all things reveals himself as “I,” and so implies that all things ultimately draw their existence from an act of a personal being acting from a first-person perspective.

Yet it would be remiss not to acknowledge at this point that the very category of “person” as I am using it here is a product of contemplative and speculative theology regarding the relationship between Jesus Christ, the One He prayed to as “Father” and the Holy Spirit whom He breathed into His followers. There is one God, and yet God is fully manifest and active in these three, these three… what? Hence the term, borrowed from the Greek stage: “person.” God is therefore the primary analogue for this notion of “person,” and God is essentially and eternally a communion of persons, a “we.” So to say from this perspective that the object of the human search for truth is ultimately a “who” and not a “what” is also to imply that this “who” is a “we” whose eternal activity is one of perfect self-giving love. It is Christ who reveals that love is not something God does, but rather what/who God is. “God’s love was revealed among us in this way: God sent his only Son into the world so that we might live through him. In this is love, not that we loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the atoning sacrifice for our sins” (I John 4:9-10). Hence Pope Benedict was able to conclude that “in Christ, love (caritas) in truth becomes the face of His person” (Caritas in Veritate 1). Truth is not only a person but has a face, a real face, such that to know the truth is to behold this face.

So what does all this have to do with this Sunday’s readings? Simply this: to pursue wisdom is to pursue truth with the recognition that the Truth is also pursuing you. It is appropriate that the passage from Proverbs 9 comes first, since indeed it is the latter movement that is primary: “Wisdom has built her house, she has set up her seven columns; she has dressed her meat, mixed her wine, yes, she has spread her table.” The truth who is a Person is waiting for us, preparing for our arrival, and also pursuing us with a continual, insistent invitation: “She has sent out her maidens; she calls from the heights out over the city: ‘Let whoever is simple turn in here… Come, eat of my food, and drink of the wine I have mixed! Forsake foolishness that you may live; advance in the way of understanding.”

This encounter with Truth only comes to completion, however, when we act through our own freedom (though always assisted by grace) to enter and embrace Him. That is why St. Paul exhorts the Ephesians so urgently to “watch carefully how you live” and to “try to understand what is the will of the Lord.” It is not enough that Truth waits for and chases after us; we must seek Truth as well. And that makes sense because the ultimate point of truth from this perspective is not “being right” or “possessing knowledge” but encountering an Other in whom we may find our salvation and fulfillment.

That brings us then to the famous gospel passage from John 6, the “Bread of Life Discourse” as it is commonly known. Rather than link it directly to doctrinal issues regarding the nature of the Eucharist, as is so often done, let us look at it through the lens of our consideration of this idea that “truth is a Person.” In seeking truth, we ultimately seek a Person, whether we explicitly acknowledge it or not. And the point of seeking truth and obtaining wisdom is likewise a personal matter: it is ultimately for the sake of our fulfillment through a loving encounter with the Other in whom all truth subsists. Or to put it another way: to seek what is true is to seek the One who can nourish us, who can satisfy our deepest longing, the longing of which our appetite to know “what is the case” is only a subordinate part.

If truth is a Person, then truth is also the bread and wine which Christ offers to us as His body and blood. It is truth itself that you hold in your hands when you receive the host at the altar. It is the one who said “I am the truth” who has “dressed her meat, mixed her wine” and “spread her table” for you in the holy sacrifice of the Mass. We may find in the Eucharist the source, the summit and even in some sense the consummation of our pursuit of wisdom, since in eating the Lord’s body and drinking His blood we simultaneously unite ourselves to His whole person and to the eternal Logos according to which all things exist and progress toward the end ordained for all creation. Truly “whoever eats this bread will live forever,” since in eating this bread one receives “I am” and so is received into the eternal act of love that is before all else.

Each act of human love is a form of death, and in such dying it could be said we are reborn in to the “the eternal act of love that is before all else”.

The word “act” may be key, as it seems not enough to understand what “die to be reborn” means. It seems inadequate to simple believe that it is true. Such matters of the head seem too easy, too weak, lying as they do on the shallow surface of our lives.

It may be that only by acting, by matching “the eternal act of love” with our own act of love that the “me” can die and be received by the “I am”.

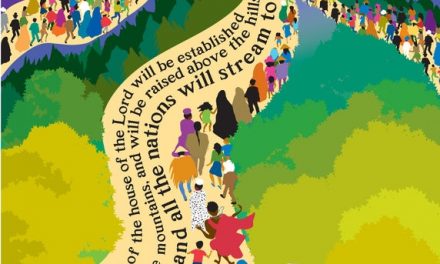

If it is true that it is the _act_ of love that liberates us from the tiny jail cell of our self imposed imprisonment and reunites us with the source of our being, then God’s message can be said to be truly catholic, fully universal. For the act of love is a choice available to all human beings in every moment of our lives, whatever our time, place, age, gender, beliefs or cultural circumstances etc.

What we might learn from 2,000 years of Christian history is that beliefs about love will always divide us, as a reader’s own reaction to this post may illustrate.

It seems that only acts of love can unite us, and observing that reality of human life may provide further guidance in to how we are supposed to be “received into the eternal act of love that is before all else.”