Is 56:1, 6-7; Ps 67; Rm 11:13-15, 29-32; Mt 15:21-28

Today’s Gospel tend to tie interpreters up in knots. For some, there is the scandal of what looks like Jesus “changing his mind.” It looks like he gets it wrong at first. So some elaborate explanation must be constructed. One homily I heard tries to make it out that Jesus is testing the woman’s faith. It’s all a ruse, to see if she really believes in him. This doesn’t seem very plausible. For others, the reading is troubling because it seems to present a Jesus offering a feeble attempt at mansplaining to the poor woman why he can’t heal her child. Fortunately, Jesus eventually is woke, but it isn’t very salutary that at first he appears to be very exclusive.

These attempts at interpretation don’t follow the direction of the Church, in the selection of the other readings for the day, that the underlying logic here is the logic of election – the idea that God has a chosen people. Election may be the most neglected idea in Christianity today, and yet it is so pertinent. In none of the readings is the idea of election rejected. Jesus’ God is the God of Israel, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

But why would God do this? How can God want a house of prayer for all peoples, but use as His means the gathering of a particular people? There are three ideas in these readings that make sense of it. First, in the reading from Paul, we hear the culmination of his great letter to the Romans, where he is wrestling with how it can be that his brothers and sisters in Israel have “missed” the Messiah. Paul insists – as should we – that God’s covenant is irrevocable. Election is not removed. Rather, Paul explains the logic in terms of God’s mercy – the pattern is to make sure all recognize their solidarity in disobedience, so that all might receive God’s mercy. In Romans, those without the Law are simply lost in the world, wandering around following the spirits of the age. But those with the Law are tempted to righteousness. The reconciliation is effected by all coming to recognize their disobedience. All have sinned and fallen short.

The need for God’s mercy is meant as an ultimate judgment on any form of human righteousness. Hence, the second point is that the “winning argument” made by the woman in the Gospel is not some counterthrust to Jesus’ exclusivism. Rather, it continues her humility: “even the dogs eat the scraps from the table.” Again, the logic of election is not revoked. She is frank in her recognition that she does not “deserve” what she is asking for.

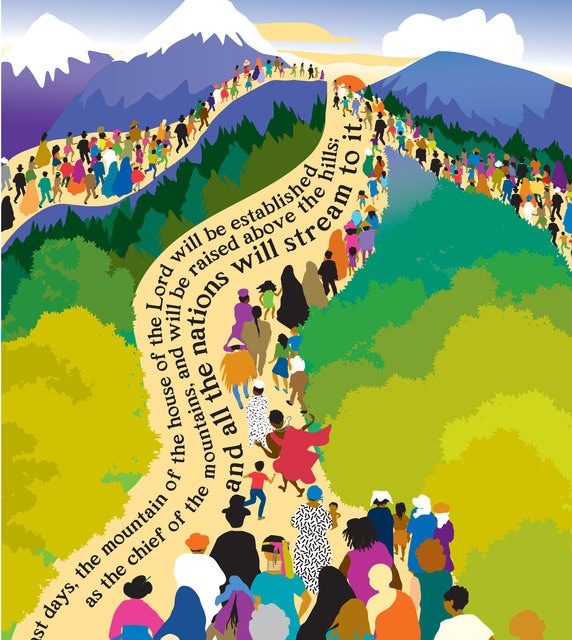

The third point is seen in the beautiful first reading, where all nations come streaming to Israel’s God to worship. This is not some pluralistic assembly of different ideas, but rather a coming together of all the nations. As the Psalmist says: “O God, let all the nations praise you.” The unity of the human race comes about in and through the worship of Israel’s God. In Christ there is no East or West or South or North. This isn’t a denial of particular identities, but a uniting of them under one God. Again, the idea of election is not revoked. Israel’s God really is the God of all the nations.

This is hard for us. Very hard. It makes it sound as if God is against all other religions – or (worse) that “we” have the right one. Vatican II’s teachings on the religions of the world in Nostra Aetate and Lumen Gentium is extremely hospitable to the real wisdom and even worship in other traditions. And so it encourages dialogue, at least with those who in one way or another seek to worship a higher power. But it is not a matter of “all religions are basically the same.” Again, this is a nice thought, but naïve. They are not. Some are truly awful.

And often enough, humans sneakily go around making up idolatrous beliefs, even if they don’t label them “religions.” Any time humans enthuse about finite person or movement in terms of fairly ultimate salvation, one should get worried. Perhaps election is made somewhat easier by noting that the claim of God’s having a chosen people means that all other human claims of being “the chosen people” – or master race or whatever – are shown up to be false. White supremacists and America First nationalists should be rejected by Christians without any reservations specifically because their claim is an attempt to falsify God’s choice. White people or Americans are not God’s chosen people. Period. And it is no wonder that, from the Romans to the Nazis, those who claimed to be the superior group needed to obliterate God’s true chosen people.

But we may wonder why there has to be a chosen people at all. “Imagine all the people living life in peace… I hope someday you’ll join us, and the world will be as one.” It’s not entirely clear to me whether John Lennon’s fantasy (no possessions?) is ultimately any less dangerous than that of the master racists. In part, the fantasy is considerably more tempting to us today than the other one is. This requires some thought about human sinfulness. What is the root of our problems, anyway? Those “other people”? For Christianity, the root problem is that we want to be God. That may be a matter of each individual wanting to be God. We see that in the Adam and Eve story. Or it may be that “we” – even the whole human race – want to be god together – as depicted most trenchantly in the Tower of Babel story. So our root problem is worship. And yet directly related to that problem is the fact that our worship – and much else – ends up dividing us into groups against one another. We are, as the psychologist Jonathan Haidt puts it, “group-ish.” We thrive as human beings in communities, not as solitary individuals. Because of this, it is a fantasy – Lennon’s fantasy – that there can be no real groups at all. Heck, even Lennon says: “I’ll hope you’ll join US”! So even when we try to oppose racist fantasies, we end up creating counter-groups that look suspiciously like all-righteous chosen peoples. We seem incapable, on our own, of not falling into good-versus-evil groupings. And it’s no wonder. There really is evil in the world. And we really do work best as human beings when we work in groups with a deeply-held common good. Yet we cannot rescue ourselves by our own devices – our own theories, our own institutions. Perhaps most pertinently, we cannot rescue ourselves by uniting around the technologists who promise to build a (virtual) tower that reaches to the heavens. Guess who the chosen people end up being in THAT scenario?!

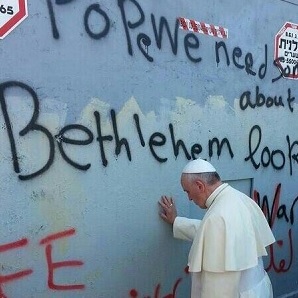

To insist on God’s election of Israel, and on the worship of a crucified Jew as the house of prayer drawing together all peoples, is to say that God subverts all this mess from within. God doesn’t save us outside our humanity, but through it. It isn’t simply a matter that humans are group-ish, and so need some kind of concrete religion. It is certainly a good thing when, at least, all acknowledge some sort of higher power, on which we rely. That’s a real humility, one that can sometimes put to shame the self-righteousness of supposed believers. And yet it is only a step on the way to the God of Israel, who reveals that higher power as one of love, justice, and mercy in the face of whatever we humans – individually and collectively – can throw at him.

Jesus, in today’s Gospel, is acknowledging his fundamental mission, as the Promised One for Israel. He is God coming for his people – but his people are ultimately, as Isaiah and the Psalmist and Paul all see, all the nations, who come to worship that God of Abraham. Even us dogs get scraps from the table. We spend a lot of time in our world casting about for other things that will save us, other groups that will somehow transform things and make them right. There is no other thing that will save us. These idols will only tear us apart. There is only one God, who loves all and seeks to have mercy on all: the God of Abraham and the God of Jesus Christ. That God saves. Let all the nations praise.