Micah 5:1-4a

Psalm 80:2-3, 15-16, 18-19

Hebrews 10:5-10

Luke 1:39-45

At the end of this most violent of years, in which the world has bore vivid witness to thousands of murders at the hands of terrorists, tyrants, criminals and even the police, this Sunday’s lectionary readings invite us to consider the theme of peace. The first reading from Micah ends with a line that at first glance might seem overly poetic or even naïve: the future ruler of Israel, coming forth from the tiny hamlet of Bethlehem—“he shall be our peace.” The reading makes an identification where at most what seems called for is an association. The prophet does not say, for instance, that “he will establish peace” or that “peace will follow from his just rule,” but simply “he will be our peace.” One could debate the semantic details, of course, but the rendering in English at least invites the question of what the meaning of “peace” is in this prophetic-messianic context.

The simplest definition of peace, of course, is the absence of violence. Yet the Judeo-Christian tradition has never been content with this minimal description. As the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church reminds us:

In biblical revelation, peace is much more than the simple absence of war; it represents the fullness of life (cf. Mal 2:5). Far from being the work of human hands, it is one of the greatest gifts that God offers to all men and women, and it involves obedience to the divine plan. Peace is the effect of the blessing that God bestows upon his people (CSDC §481).

In short, peace and violence are social expressions of human beings’ relationship to Creator God. The entire history of salvation, in fact, can be reduced to God’s ongoing attempt to reestablish the peace that has been lost through human sinfulness. One reason why God performs this work through a people rather than with every particular individual is that what He is ultimately trying to bring about is a corporate reality that must be shared in order to be fully manifest.

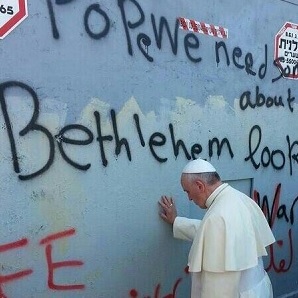

Even between particular individuals, true peace can never unilaterally imposed. That kind of “peace” is simply another form of violence. In this regard, I cannot help but think of my own experience of Bethlehem when I visited there several years ago. Driving out of Jerusalem, one begins to see within minutes the truly imposing “separation wall” that serves as a buffer between Israeli and Palestinian controlled territory. Our Israeli tour guide cheerily explained to us how this 8-meter-high (26 ft.) wall has resulted in a dramatic decrease in terrorist violence at the hands of the Palestinians. True as that may be, has it really brought “peace” in any meaningful sense? I could not help but find the sight of Bethlehem surrounded by this enormous wall both deeply ironic and deeply distressing. Unlike the ancient walls of Jerusalem, it was not built to keep people out, but rather to keep people in. The price of peace in this instance is to barricade the birthplace of the Prince of Peace. As it was that blessed night when our Lord was born under the open air, the world today is too consumed with achieving and maintaining its own security to attend to the radically insecure ways in which God is establishing peace in our midst.

It was Tacitus who said of his own people that “they make a desert and call it peace.” In our own day, I often feel as though we do the same, except instead of “peace” we call our deserts “security.” It is a remarkable irony of history that only after the Church found its “peace” with the Empire that many of its members began to flee to the desert to find true peace. Like so many before them, including Jesus himself, the disciples and spiritual descendants of St. Antony found a fullness of life in the desert which no other locale on earth could offer. They went to the desert and discovered the true meaning of peace. The key to this peace, however, is the patient anticipation and obedient acceptance of a gift that one cannot give one’s self. The desire for peace is good and natural in the wake of the appalling violence our nation has experienced this Advent season. Yet we Christians must remember that, insofar as Christ himself is our peace, we cannot make peace by our own willful determination and our own strategic efforts, however creative.

There seem to me to be two chief responses to the violence that continues to rage around us in the present moment, and they both come from a very deep place in our natural history: fight or flight. When faced with a situation that seems dangerous and out of control—one that could conceivably threaten our own well-being—we either flee and fortify, retreating into a safe place with sufficient provisions and safe assumptions, or we fight, attempting to impose control somehow upon the chaos and unpredictability of events. Some of the political strategies proposed by politicians and media figures fit neatly and cleanly into one or another of these categories, but in many cases the same voice or platform will swing from one impulse to another: “don’t let anyone in the country,” and “go after their families”; or “we all just need to learn to get along and accept each other” and “to do that we must insist upon a secularist public square.” While understandable, both sets of reactions stem from the one state of being that the Bible clearly rebukes again and again over the course of salvation history: fear.

Like Israel with her sin offerings and holocausts, we think there is some way to counteract that which we fear by way of concrete acts that we can perform in the short-to-middle term. Like them, we think we can find and execute a formula to establish peace or at least “give peace a chance.” But what sort of peace are we hoping to achieve? Part of the ongoing impetus toward new gun legislation is doubtless borne out of a genuine desire for social concord, but much of it seems to be a frantic attempt to “do something” so that people intent of violence do not have the opportunity to carry it out. Likewise with the impetus to arm more citizens so that they can actively oppose at any moment those who attempt to carry out such violence. Regardless of the merits of each proposal, we as Christians should recognize that neither strategy aims for true peace. No matter how needed or prudent increased gun control may be (and I would certainly concur with that judgment) any moment’s thought reveals how futile any politically based theodicy would be in the face of the enormous losses we all have witnessed this year. The future security of my own children does nothing to diminish or explain the violence which has been endured and will continue to be endured by those who loved those who were lost.

Peace is not going to come merely from our own attempt to control the weapons of war, to install more effective security apparatuses, or to build more resistant security barriers. If the narrative of our Lord’s nativity teaches us anything, it teaches us that we can neither simply impose peace nor strategize a path to its inevitable achievement. Peace is something we must receive. Peace comes not from any Archimedean “eureka” but only from the Marian “fiat.” The peace that is born into the world at Christmas is not even something which was ultimately determined by mere Davidic inheritance alone, since it is only in virtue of Mary’s virginal betrothal that such a connection can be made. Peace appears unexpectedly, in the womb of the peasant girl with the forgotten genealogy. It is only her blood that runs through Jesus’ veins.

Peace comes to us not through any technocratic mechanism, but rather in the personage of Christ, who dwells in the poor and vulnerable among us just as much as He dwelt in the body of Mary as she stood before Elizabeth. May the Holy Spirit fill us when we encounter Him among us, so that the image we ourselves bear of Him might awaken and dance within us. Let us look to the many deserts which our own craving for security has created and repent of our feverish attempts to control history and make it “turn out right.” May we return again to the cave at Bethlehem and kneel before the Prince of Peace, offering Him the gifts which we have received from His own hand. The animals and the cold night air make it clear that He cannot ultimately offer us security, but the bright star above makes it equally clear that he can offer us the peace for which we yearn.