They were the strangest, most decent family I had ever met, and just about everyone in our parish agreed. I used to see them, sometimes just one alone, sometimes as a family, biking everywhere they went in town – rain or snow, hot or cold, a simple trip to the grocery store or heading to Mass on Easter Sunday. I could always tell it was him when I would see him far ahead of me on the road; that same, slow, rhythmic, consistent pedal speed; back perfectly erect, looking serenely straight ahead, seemingly in no hurry but clearly mindful of where he was going; unfettered by wind, rain, or snow (he would have made a model mail man). Sometimes my interactions with him and his family were awkward (OK, frequently they were awkward); and yet, I always came away feeling bewildered by how such seemingly strange people always had the effect of both calming my anxieties, and at the same time challenging me to set aside my own judgments and appreciate the steady, consistent virtue that they exemplified. There is no other word to describe my interactions with them than “bewildering.”

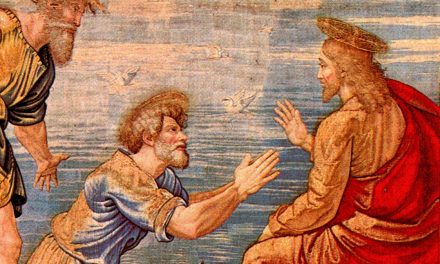

Today’s readings take us to the beginning of the heart of the Christian mystery – the suffering, death, and resurrection of Christ. In the procession at the beginning of the Palm Sunday liturgy we hear the story from Matthew’s gospel of Jesus entering Jerusalem riding on a donkey (21: 1-11). And he is hailed by the crowds who proclaim him “the Son of David” (v. 9; cf. Psalm 118: 26), a clear reference to their Messianic hopes for Jesus’ arrival in Jerusalem. Could this be the one who will overthrow Roman rule and re-establish the kingdom of Israel? The whole gospel has been leading up to Jesus’ entry to Jerusalem and his subsequent suffering and death, which he has foretold (or warned?) his disciples about repeatedly throughout his ministry of preaching and healing (16:21-23; 17:22-23; 20:17-19; 26:1-2). And yet, no matter how many times he tells them this, the disciples seem incapable of grasping this reality until they themselves have experienced the risen Lord. Even Peter, immediately following his proclamation that Jesus is the Messiah, and being told that

you are Peter [Gr. Petros] and on this rock [Gr. petra] I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it (16: 18)

immediately turns and rebukes Jesus for predicting that the Messiah must undergo “great suffering,” to which Jesus replies: “Get behind me, Satan! You are a stumbling block to me; for you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things” (16:23). In another brilliant word-play, Matthew uses the word skandalon (meaning a stumbling block) to describe Peter – the rock, that large chunk of dense earth – indicating that he is the one who is capable of being both a skandalon and the rock that would become the foundation of the church. [Elsewhere Matthew plays with the verb and noun forms of this same word when Jesus says “Whoever causes to fall [skandalise] one of the little ones who believe in me…Woe to the world because of such a stumbling block [skandalon]” (18: 6-7).]

Of course, Peter is not the only one to waiver during the trials that make up the mystery of Christ’s suffering and death leading to his resurrection. The crowds who gather to hail Jesus as the Son of David (a phrase clearly referring to Jesus as a messianic prophet, fulfilling Nathaniel’s prophecy to king David; 2 Sam 7), will soon turn into the crowds who demand the release of Barabbas and ask Pilate to have Jesus crucified. And Peter, poor Peter – thick as a rock [Petrus] – will stumble [skandalise] again in denying his status as a disciple while Jesus is being questioned before the High Priest, and will weep bitterly at his own failure (26: 69-75). Meanwhile, the rest of the disciples, who cannot even stay awake for a few hours to pray with Jesus, are scattered in fear and confusion after Jesus’ arrest. Truly, the prediction that

I will strike the shepherd

and the sheep of the flock

will be scattered (Matt 26:31; quoting Zech 13:7)

comes true with a vengeance. Few, it seems, are capable of remaining steady and faithful amidst such tribulations, no matter how many times Jesus has tried to prepare them for this moment. In a wonderful, and still challenging, literary twist the exceptions here seem to be those faithful women mentioned in the gospel who stay close to Jesus throughout any and all of his tribulations, and are the first to witness to the empty tomb and the resurrected Jesus: Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James and Joseph, and the mother of the sons of Zebedee (Matt 27: 55-56; 28: 1-10).

And yet, if this were the final chapter, upon what basis would any of us (especially us men!) have any hope of achieving the kind of virtue that allows us to hold fast to the gospel and find salvation? Fortunately, “For mortals it is impossible, but for God all things are possible” (19:26). In these moments of failure, we can certainly identify with the Psalmist who laments, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Psalm 22: 1).

It is into a similar situation of trials that Paul addresses his letter to the Philippians, and exhorts them with the model of Christ’s faithful obedience to his role as the Messiah. In this beautiful, ancient hymn of the church, Paul reminds us that the way to God’s glory is through the self-emptying that Christ exemplifies in his Incarnation, and in a distinctive manner in his suffering and death. Here I cannot help but be reminded of the commentary upon Jacob’s ladder (Genesis 28:10-19) provided by St. Benedict in his Rule:

Hence, brethren,

if we wish to reach the very highest point of humility

and to arrive speedily at that heavenly exaltation

to which ascent is made through the humility of this present life,

we must

by our ascending actions

erect the ladder Jacob saw in his dream,

on which Angels appeared to him descending and ascending.

By that descent and ascent

we must surely understand nothing else than this,

that we descend by self-exaltation and ascend by humility.

And the ladder thus set up is our life in the world,

which the Lord raises up to heaven if our heart is humbled.

For we call our body and soul the sides of the ladder,

and into these sides our divine vocation has inserted

the different steps of humility and discipline we must climb (Rule of St. Benedict, ch. 7).

Thus, even amidst great suffering and tribulation, which Jesus tells/warns us about from the very beginning (24:9-12), there is always the hope and the promise that God will sustain us through God’s faithfulness. Relying not upon our own strength, but rather the grace and the mercy of God, we find hope in the belief that

the one who endures to the end will be saved. And this good news of the kingdom will be proclaimed throughout the world, as a testimony to all the nations (24:13-14).

Therefore, as we enter into this Holy Week with the jubilation and shouts of the crowds’ rejoicing ringing in our ears, the author of Matthew reminds us of the many saints who will stumble in the confusion and tribulations that are to come, and encourages us with the examples of the women who remain faithful. The gospel writer seems to be beckoning us to become as much like the women mentioned above as is possible: steady in our trust, even when hope is challenged. And we are reminded that even those who stumble are given the opportunity to be forgiven and to continue to spread the good news. This, I suggest, is the essence of Christian virtue: to remain steady through whatever storms and tribulations may come – and come they will. Like my fellow parishioner on his bicycle, we are called to keep up that steady cadence and calm resolve through any and all situations – neither rain nor sleet nor hail nor wind… In doing so, perhaps we will become a stumbling block [skandalon] causing others to ponder with the same kind of bewilderment how it is that we have received the gift of steady, self-emptying love that keeps us pedaling ahead in hope.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks