The following is a guset post from Dr. Alessandro Rovati, Adjunct Professor at Belmont Abbey College.

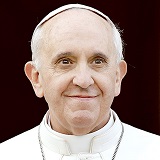

There have been so many comments on the encyclical Laudato Si, but not many have focused on an overarching element that is decisive to appreciate what Francis is telling us. This text is first and foremost a powerful witness of how someone who lives in light of the Resurrection looks at and interacts with every single aspect of reality: economics and politics, other living creatures and fellow human beings, nature and societies. Reading the encyclical, one finds the invitation to learn that the Resurrection is the keystone of newness in the relationship between me and myself, between me and people, between me and nature. Pope Francis does not invite us to share a “green” ideological agenda, rather he challenges the faithful to learn to look at all creation with awe and wonder, realizing that “everything is, as it were, a caress of God.” (84)

Called to Live the Encounter with Christ – Francis addresses the encyclical to “every person living on this planet […] to enter into dialogue with all people about our common home,” (3) but he also emphasizes that we Christians are called to a special responsibility when it comes to the care for the whole of creation. We need to “better recognize the ecological commitments which stem from our convictions” (64) so that we might learn to live the encounter with Jesus Christ in our relationship with every facet of reality.

The “integral ecology” (137) proposed by Francis is a distinctive and “new way of thinking about human beings, life, society and our relationship with nature” (111) that cultivates new habits and lifestyles, and educates all of us to an attitude of the heart “which accepts each moment as a gift from God to be lived to the full.” (226) It is the imitation of Jesus and the identification with his way of looking at people and things around him that kindles the heart of the faithful and converts them to this new life. Jesus’ gaze was full of fondness and wonder, for he constantly recognized the paternal relationship that God has with all creatures, so much so that everything – even the smallest of things – recalled him to the relationship with the Father (Jn. 4:35). “Jesus lived in full harmony with creation, and others were amazed” (98) because his gaze and his gestures affirmed the infinite value of everyone and everything, making present in the world the impassioned mercy with which God looks at all his creatures.

Now, the recognition of the world as God’s loving gift, the gratitude and gratuitousness that spring forth from such an awareness, and the perception of the universal communion with other creatures that faith teaches us are not without consequences. In fact, “the teachings of the Gospel have direct consequences for our way of thinking, feeling and living.” (216) All those who want to draw a line between the Church’s ‘spiritual and religious’ guidance and the ‘public and political issues’ of the day – and there were many both before and after the encyclical was published – fail to understand that faith permeates life in its entirety. If that were not the case, and faith were unable to speak to and redeem the present situation in which people live, it would “sound tiresome and abstract,” (17) and would inevitably fail to fascinate people and convert them. Instead, “the life of the spirit is not dissociated from the body or from nature or from worldly realities, but lived in and with them, in communion with all that surrounds us.” (216) Which is why Francis’ bold and courageous proposals are all ultimately rooted in the “gospel of creation” (62) that Christians discover by being “open to God’s grace and [by drawing] constantly from their deepest convictions about love, justice and peace.” (200)

Beyond Party Lines – Above all, the Pope constantly shows a special gift for avoiding any form of reductionism. The integral ecology spelled out by Francis is so powerful precisely for the breath and depth of the gaze on reality that it embodies, one that does not forget any element of our life. In this text the Pope shows us “how inseparable the bond is between concern for nature, justice for the poor, commitment to society, and interior peace.” (10) The text challenges – at times, upsets – people across ideological and party lines, both within and without the church, a fact that speaks to the irreducible novelty that springs from the life of faith. No one is left untouched by the prophetic call of this encyclical because the Pope addresses the deeper issues that our common mentality – even when it is generously concerned with environmental and social problems – usually avoids. “What kind of world do we want to leave to those who come after us, to children who are now growing up? […] What is the purpose of our life in this world? Why are we here? What is the goal of our work and all our efforts? What need does the earth have of us?” (160) By taking us to the heart of what it means to be human, Francis invites all of us into a journey of reflection, conversion, and meaningful change. Will we be open to his invitation?

The Educational Challenge – Every journey is made of steps, and the Pope is well aware of that. “Many things have to change course, but it is we human beings above all who need to change.” (202) New laws and technologies will not suffice; instead “a great cultural, spiritual and educational challenge stands before us, and it will demand that we set out on the long path of renewal.” We are to build a new humanism “capable of bringing together the different fields of knowledge […] in the service of a more integral and integrating vision.” (141) Authentic care for our common home requires the concurrent promotion of an economic ecology, a social ecology, a cultural ecology, an ecology of daily life, and a human ecology.

While many people are starting to realize that our current model of progress, patterns of production, and compulsive consumerism are at the root of many of the world’s problems, nevertheless we live in a milieu that makes it difficult to develop new habits. Every age progresses, produces, and consumes. It is part of human nature, and it is also part of the divine vocation of tilling and keeping the earth. (Gen 2:15) The problem nowadays is that our throwaway culture is based on the lie that people “are free as long as they have the supposed freedom to consume,” (203) as if the continuous accumulation of goods were able to fulfill the human heart. Reality shows us that what happens is quite the opposite, as the “constant flood of new products coexists with a tedious monotony.” (113) The result is a people who becomes self-centered and self-enclosed, unable to accept the limits of reality, and always struggling to manipulate the world around it to meet its unsustainable expectations and needs. “Obsession with a consumerist lifestyle, above all when few people are capable of maintaining it, can only lead to violence and mutual destruction,” (204) for when all that matters is the satisfaction of our own desires and immediate needs, what limits can be placed on the exploitation of nature and fellow human beings?

Yet all is not lost. “We are able to take an honest look at ourselves, to acknowledge our deep dissatisfaction, and to embark on new paths to authentic freedom. No system can completely suppress our openness to what is good, true and beautiful, or our God-given ability to respond to his grace at work deep in our hearts.” (205) The educational challenge that is in front of us – especially within the Christian community – is to help people to rediscover, foster, and cherish the God-given ability to recognize what truly corresponds to their infinite yearning, so that they may resist the false promises of the dominant paradigm and thus be truly free. When Francis calls us to a new and simpler lifestyle capable of embodying a greater reverence for life, a deeper commitment to sustainability, and a real care for justice and peace for all, he does not do so in light of an abstract and mortifying moralism. Instead, “such sobriety, when lived freely and consciously, is liberating. It is not a lesser life or one lived with less intensity. On the contrary, it is a way of living life to the full.” (223) The greatest contribution that the Church can give to our troubled world, in fact, is to educate a people who discovers in an alternative understanding of wellbeing the possibility of deep enjoyment and true freedom.

We live in troubled times, and we have a long journey ahead, along which we will have to struggle with the indifference, self-interest, and opposition of many, but “in the heart of this world, the Lord of life, who loves us so much, is always present. He does not abandon us, he does not leave us alone.” (244-45)

You said…

“If that were not the case, and faith were unable to speak to and redeem the present situation in which people live, it would “sound tiresome and abstract…”

While meaning no disrespect to the Pope, who I sincerely see to be a welcome breath of fresh air, I must admit…

I find his writing on the environment to be very well meaning and highly articulate, but failing to redeem the present situation, and thus regrettably tiresome and abstract.

The present situation is that the environment we depend on is falling apart all around us. If climate change should race over a tipping point during the next century the result could be no more peace, no more sanity, no more Catholic Church, no more humanity.

In spite of the pressing nature of the present situation, the Pope seems to fall victim to that most Catholic of afflictions, an excessive fondness for grand sweeping philosophical moral proclamations (an affliction shared by this writer).

The Pope seems not to realize that we’re running out of time for that method of change, however advisable it might have been in earlier eras.

The Pope has earned the ear of a billion human beings. He should call upon them to act as one in taking some clearly identified specific measurable action which would have direct positive impact on the reality of our current situation, and serve as a leadership example for the rest of humanity.

The Catholic Church might be seen as a cherished grandparent who is very old and very wise, but also very tired. Clinging fondly to the comfortable familiar patterns of the past is unlikely to ensure a future for The Church and humanity.