Paul Elie wrote a column in the New York Times on Friday suggesting that Catholics ought to consider “giv[ing] up Catholicism en masse, if only for a time.” If Benedict can resign, says Elie, so can we:

For the Catholic Church, it has been “all bad news, all the time” since Benedict took office in 2005: a papal insult to Muslims; a papal embrace of a Holocaust denier; molesting by priests and cover-ups by their superiors. When the Scottish cardinal Keith O’Brien resigned on Monday amid reports of “inappropriate” conduct toward priests in the 1980s, the routine was wearingly familiar. It’s enough to make any Catholic yearn to leave the whole mess for someone else to clean up.

Elie says he’ll go back to his Brooklyn parish after Lent. But he thinks protest might be helpful to a church that has lost its way:

A temporary resignation would be a fitting Lenten observance. It would help believers to purify and deepen our faith in the light of our neighbors’ — “to examine our own religious notions, to sound them for genuineness,” as the American writer Flannery O’Connor put it. It would let us begin to figure out what in Catholicism we can take and what we can and ought to leave. It might even get the attention of the cardinals who will meet behind the locked doors of the Sistine Chapel and elect a pope in circumstances that one hopes would augur a time of change.

I count myself as a Paul Elie fan and I’m sympathetic to many of his points. Like many of my colleagues (see here and here), I’d paint a somewhat more complex picture of Pope Benedict’s papacy, but I can understand the resignation that would drive someone to a fast of this kind.

Yet Catholicism is so complex. There is so much beauty amid the ugliness about which Elie so rightly speaks. Just this week, at St. Louis University, I experienced some of that beauty.

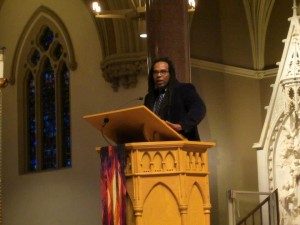

The SLU community gathered to hear Dr. Jonathan Smith from the Department of African American studies read Fr. Claude Heithaus, SJ’s famous 1944 homily that ended racial segregation at SLU. In the summer of 1944, SLU became the first school in St. Louis and the first university in any of the 14 former slave states to admit non-white students.

Fr. Heithaus begins his homily by shaming Christians and calling them to honor the truth of their faith above social conventions:

It is a surprising and rather bewildering fact, that in what concerns justice for the Negro, the Mohammedans and the atheists are more Christ-like than many Christians. The followers of Mohammed and of Lenin make no distinction of color; but to some followers of Christ, the color of a man’s skin makes all the difference in the world.

He ends by calling the congregation to stand and repent of their cooperation with evil:

For the wrongs that have been done to the Mystical Body of Christ through the wrongdoing of its colored members, we owe the suffering of Christ an act of public reparation. Let us make it now. Will you rise please? Now repeat this prayer after me. “Lord Jesus, we are sorry and ashamed for all the wrongs that white men have done to Your Colored children. We are firmly resolved never again to have any part in them, and to do everything in our power to prevent them. Amen.”

As I stood in the College Church repeating these words I was struck by the way in which the universality of Christianity and its prophetic teachings from the gospel forward allowed Fr. Heithaus to see a truth to which so many remained blind. “If Jesus Christ is right, then whosoever is unfair to a Negro, even in his own mind, is wrong,” he said. And in linking his own prophetic denunciations to those of the tradition, he changed St. Louis University.

Like most Catholic universities, we still need to confess our failure to welcome a truly diverse study body. Thank God for the prophets of today (James Cone, Bryan Massingdale, Alex Mikulich, Laurie Cassidy) calling us to live the Christianity we profess.

Still, it is moments like these that keep me in my pew.

I have some sympathies for some of Elie’s views – there are definitely days when I wonder, “What the h*** am I doing here?” I would want to name and describe some of the same kinds of complexities that you’ve linked above, however – and would say that always, for me, it comes down to that I believe the Holy Spirit is alive in this Church and that this is the Body of Christ. And while sometimes it’s hard to be here, I don’t find it harder than being elsewhere…I’m saying that having been both a member of another church, and nothing, for a while. The story you give about racism is one of many, many places where I see the Holy Spirit at work in this Church.

That said – my reaction to Elie was less about the way he’s perceiving the church (because what could I say to convince him otherwise really?) and more about whether this leave-taking would really make the statement he wants it to make. In an era when the “rising nones” are the big religion news story, and when it’s easier to join and leave all manner of churches and other religious traditions (it’s REALLY easy to start your own too), what does it do to leave – even en masse – other than say, “Hey, I’m just another one of the crowd?” Back in the day when parish life was less fluid, it would have meant something – and cost even more – but these days? Not even a blip.

I was going to engage this Elie piece, too, but you beat me to it, Julie! I want to say that I too am an Elie fan, especially of his intertwined Catholic biographical study The life You Save… It may be one of the best books on 20th century American Catholicism, if not THE best.

So I found the Elie piece disappointing… and I didn’t want to. Of course he is right about the problems he cites. But I really had two problems with his response. One you’ve already mentioned – the all bad news, all the time line does not build credibility. Maybe it is a reasonable lede for an NYTimes editorial, but if he actually believes that, then he really is not giving a very rich reading of the complexities of the Catholic Church today.

But my second problem is something that’s struck me other times when I’ve read suggestions like this. I don’t understand theologically how to make sense out of such an action, especially as a Lenten observance. Now let me say, I understand walking out of a particularly bad or offensive mass in protest, and I understand withdrawing from this or that parish ministry (or parish) out of legitimate theological frustration. But I don’t understand not showing up for the sacraments. It feels to me like what you do when you are boycotting something, or when you are trying to force some kind of legislative change. But this is where I find the ecclesiology here hard to understand. It makes sense to boycott a parish, but I don’t see how it makes sense to boycott the Church. I don’t see how leaving the sacraments and the community, especially at a time like Lent, where the Scriptures and RCIA scrutinies are so rich, is somehow supposed to HELP our spiritual discernment about what needs to change about the Church.

Now I understand my perspective has autobiographical elements: my own spiritual journey is Catholic, I never had any falling away crisis (partly because of tremendous good fortune in my high school, Northfield’s parish, and Anne Patrick), I’ve had good communities and bad communities. But apart from this, I really do have a hard time understanding theologically what is going on when pew protest/resignation involves not showing up. Elie says it arises out of a desire to “leave the whole mess” (even temporarily) – but isn’t this exactly what the Church and the Incarnation is? Not leaving the whole mess? By all means, let us have clear judgments about the mess. Let us have vigorous discussions about it. But absences of protest/boycott seem like a genre of action that applies to democratic governments and competitive markets, not to Catholic ecclesiology.

I’m very open to illumination here…

Jana and David,

I also have a difficult time understanding how this sort of fast could be Lenten. It seems more like a hunger strike designed to move the institution. Though Elie insists it would also help us discern what is essential, I have a hard time seeing how it would do that. I tend to agree that staying is the harder choice today, though I believe that those who leave also have a role in bringing about the larger reforms that I hope for. My experience at SLU was so moving because yes, I sense the Holy Spirit at work, but also because it forced me to think about my complicity and that of my institution. Both the beauty and the messiness (my own and that of the church) contribute to my need and desire for Christian community.

Setting aside Elie, Fr. Heithaus’ homily is inspiring, and it is certainly one of those documents of the “pre-Vatican-II era” that is striking. Like social prophets John Ryan and Virgil Michel (to name a few), there was a kind of Catholic confidence and boldness that seems today either (a) entirely lacking, or perhaps worse (b) limited to a very small number of issues whose selection is open to question.

But the tone is also interesting: it is not “pastoral” in a gently-leading sense, is it? It’s a public shaming. Do we have the ecclesiology to support such an appeal to a sense of sin and shame over our complicity in the evils of the world today? Julie, I think your work on connecting personal and social sin, and on recovering (appropriately chastened) some of the resources of the manuals is exactly right.