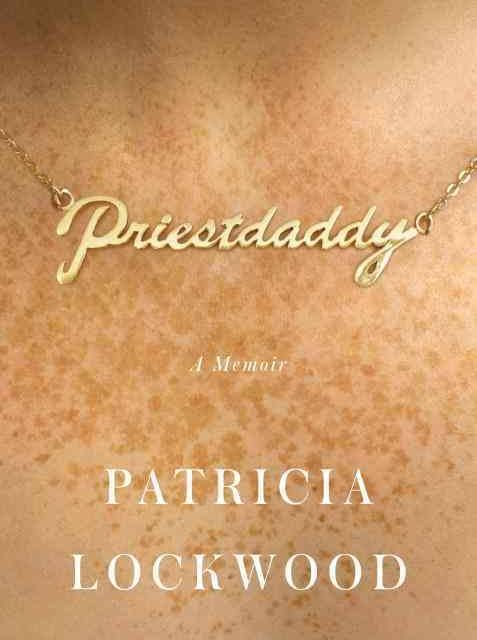

I recently read Patricia Lockwood’s memoir Priestdaddy. Lockwood is a poet with a unique backstory—her father is an ordained Catholic priest.

My original intention for picking up the memoir was to gain insights into what it might be like to have married priests with families. Lockwood doesn’t give us much in the regard. Her father is almost a caricature, not a real person. He is overweight, fiercely conservative, spending his time at home in his study lounging in his underwear and listening to Rush Limbaugh and watching football. When his adult children and grandchildren visit, he makes a five minute appearance and then is conspicuously absent. It is like he likes the idea of procreation more than the reality of fatherhood. Lockwood herself does not seem to know him well. At one point, she mentions that if more priests were married, we would have avoided much of the sex abuse crisis. This is naïve. Lockwood’s experience has little normative significance for me as far as the argument regarding married priests go. And if you are looking for that in the book, you will be disappointed.

The book, despite not fulfilling its purpose for me, was a worthy read. Lockwood has scathing critiques of the Catholic Church, particularly of its male-dominance and of the sex abuse crisis. She mentions hearing with total disgust of a priest kissing a fourteen year old. “She shouldn’t have put him in that situation,” say her father’s conversation partners. It is awful, inexcusable, disgusting and Lockwood wants us to feel that. She makes us ashamed to be Catholic, to be associated with such fierce, destructive hypocrisy.

And yet.

The book, despite its irreverence, its intentional offensiveness, its often puerile humor (and the book is really, really R-rated), is also strangely Catholic. Lockwood, as a poet, has a way of seeing reality in a way that is deeply sacramental. No event, not thing is incapable of elevation. There is, whether Lockwood intends it or not, a thread of sacramentality that weaves its way throughout the book. And while Lockwood, unsurprisingly, considers herself a lapsed Catholic, she does not consider herself a lapsed believer at all. There is a faith and love that she cannot shake, a way of looking at reality that is hopeful. It is very much a Catholic book.

The book reminded me a lot of John O’Toole’s Confederacy of Dunces or one of Walker Percy’s works. The people who identify as “heroes” (the good guys) are bizarre anti-heroes, not so much evil as totally unreasonable. And yet, they have a lovability too. They have a goodness that transcends even there own ability to disgust and repel us.

Lockwood’s own experience of family is also profoundly Catholic. Her sister is a conservative who drives a big van with seven kids who spout Latin and pray Hail Mary’s. Her father wears a cassock. Her mother, while faithful, hates nuns and is, in everyway, affirming of Lockwood’s own vocation as a sort of X-rated troubadour. Her family is far from homogenous, far from what we might call the ideal of a Catholic family, and yet there is a unity of love, a unity of identity that is attractive and good. Lockwood misses her father but does a great job portraying what modern Catholic family life might look like.

Not everybody should read this book. But for Catholics with a deep appreciation for the Catholic imagination—Catholics who do not make a fierce distinction between the sacred and profane–this book is a modern contribution. It is a book not about goodness, but about grace.