Yesterday my Saturday morning began (as it so often does) with the New York Times, and in what is starting to seem quite common, a cover story of a violent and public rape. This week it’s Brazil (“Public Rapes Outrage Brazil, Testing Ideas of Image and Class”), but there was very little new or unique about it. Over the last six months, the violent and pervasive reality of a global rape culture is everywhere we turn – Steubenville, Connecticut, India, Egypt, Juarez, and now Brazil. Despite the fact that Brazil has taken numerous steps to protect women’s rights (such as women-only subway cars and female-led sexual assault police teams), rape is on the rise in Rio, a scary reality as it gears up for the Olympics and World Cup (as large sporting events are perhaps the largest hotspots for sex trafficking).

All of these attacks – from Steubenville to Brazil – were public attacks. Women are being beaten and raped in public. I don’t know why this shocks me, but it does. In fact, the rapes in Brazil only generated public outcry when an American was attacked. It wasn’t until a certain type of woman—one viewed as being of a higher class or privilege—was attacked that society paid attention. This raises significant questions about race and class, yes, but even more than that, it makes quite clear that the full dignity and humanity of women still needs to befought for everywhere. We have in front of us a global rape culture within which women are victims of not only individual instances of violence but a deep social structure in which sexual violence is accepted. Are we going to do anything about it? At what point will we say ENOUGH?

In many of the commentaries and blogs about rape culture, there is an ongoing massive debate concerning feminism. As a teacher, I am always struck by the negative reaction to the word – feminist. In the United States, there is this lulling complacency born out of a very dangerous delusion that we don’t need feminism anymore, we have already achieved equality. Students acknowledge that it is needed in “other” parts of the world and was “needed in the past.” The suffragettes, the equal rights movement – they were important but that’s over here in the United States. My own teaching tactic has generally been to respond with data on pay inequity, etc. But I now realize that these arguments simply play into the narrative that the “real battle is over” and that the seeming urgency of feminism is just a quibble about pennies.

As I have noted before, 1 in 4 female college students will be sexual assaulted before graduation. In Steubenville, a young woman was unconscious and raped while others watched. In the aftermath, I had a few conversations with my freshmen about rape and sexual assault – trying to unmask the scary assertion by a number of Steubenville bystanders that they didn’t realize it was rape. What constitutes rape? What is sexual assault? These honestly have never seemed like difficult questions to answer and I could never understand the supposed ambiguity concerning sexual assault and sexual harassment….until yesterday afternoon at the ballet.

My mom, sister and I went to the matinee at NYC Ballet for a “Tribute to Broadway,” which included the Bernstein/Robbins classic, Fancy Free. A one-act ballet about three sailors on a night’s shore leave in NYC (1944); the dancing and athleticism of the performers was impeccable. The show, however, was sexual harassment dressed up as “good fun.” As an unknown woman walks down the quiet, dark street, the three sailors leer, flirt, manhandle and surround her. The sailors prevent her from leaving, then take her purse and pass it around. When she finally gets loose, two of them follow her off stage. Now we are meant to believe that when they come back and join the third sailor and his date, she has done so of her own free will, but why? (Because times were different then? Because they’re good American sailors?) As the lights went up for intermission, I heard the pre-teen a few seats down from me say to her parents, “Well that was great! This is fun!” I desperately wanted to lean over and tell her that no, that wasn’t great fun – yes, it was great dancing, but they just choreographed sexual harassment; it will not seem fun if you are the one surrounded by three sailors blocking your path down the street.

Fancy Free is considered a modern ballet classic that put choreographer Jerome Robbins on the map – and virtually no critics note the fundamental problem with the ballet’s message. Preparing for this blog post, I was shockedby the number of reviews which claim that this ballet never crosses the line into “actual sexual harassment.” You must be kidding! If this isn’t sexual harassment, what is? And, now we’re back to the persistent public debates about what is “real rape?” It also perpetuates a dangerous narrative concerning sexual harassment, sexual assault and rape within the military. If this is “good fun,” then what does that mean for women in the military?

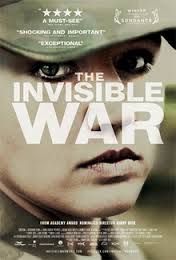

The Oscar-nominated documentary Invisible War has forced a public conversation about the epidemic of sexual assault in the United States military and the deep culture of concealment and cover-up that exists there. Invisible War makes us face the structural violence done to women in the military and dismantles any illusions of isolated scandals and a few bad apples. This is social sin, not an isolated incident or a matter that affects only a handful of individuals. Structural sin such as this goes beyond the question of the individual responsibilities of perpetrators. More than 20% of female veterans have been sexually assaulted during their service. One of the most recent scandals was at Marine Barracks Washington, DC (these are the elite Marines who guard the President, foreign dignitaries, etc) – of those who reported sexual assault, 4 out of 5 women face punishment and no rapists have been punished. In units where sexual harassment is tolerated, like Marine Barracks Washington, incidents of rape triple.

Sexual violence is not about sex or sexuality. It is about violence and power – and both women and men are the victims. Veterans who were victims of sexual assault have a higher incidence of PTSD than combat veterans. Almost universal in the stories of those who have come forward (spanning all the way back to 1944 and the “glory days” of Fancy Free), the soldiers describe the betrayal of the US military after they were raped as worse than the rape itself. Victims are blamed, punished, ostracized and often intentionally placed in the path of their assailants. There is a public and communal character to the culture of sexual assault in the US military – something that Chuck Hagel is at least publicly claiming is a priority for the DOD. The movie prompted Leon Panetta to remove decisions concerning rape accusations from the commanding officer. What happens next remains to be seen, but in December 2011 a lawsuit by thirteen sexual assault victims against the Department of Defense was dismissed, citing a 1950s decision that says that military personnel cannot sue the US Government for anything incidental to military service (ie. you cannot sue the army for malpractice for care received in a military hospital or for combat injuries). Dismissal of the case essentially says that rape is incidental to military service. To quote my sister, “Men and women joining the military consent to the risk of being shot; they do not consent to being raped.”

As a Catholic feminist ethicist, I am currently struggling with the silence of my own community on the structural sin here. There are a handful of theologians writing on the hookup culture, domestic violence, and sexual violence in war, but these conversations are small and largely relegated to the edges of our moral theology conversations. Catholic public debate on violence against women is virtually nonexistent, even as we are about to launch a second fortnight for freedom – this time on same-sex marriage and the Supreme Court. Why isn’t rape culture and violence against women a priority within Catholic moral theology? This is a question I will continue to grapple with as I discern how to engage this as a moral theologian. Yet, this Sunday, I will take one small step in dismantling rape culture by calling out the “pretty and sanitized” sexual harassment we dismiss as “good fun” or “harmless” and write a letter to the New York City Ballet.

*This post can also be found @ Millennial Journal

Meghan, your determination to keep this conversation going is so vitally important. Yet, it is a conversation that lurks below the surface, because it seems that as a people, we are stalled at dealing with crimes of power expressed in sexuality. Like the American woman in Brazil, we notice when something permeates our thick skins, we make some noise and move on.

Growing up in the late 50’s and into the 60’s, the drumbeat of how a woman was most likely at fault if she was raped, was ever present. It might be the more “benign” implication that she dressed in a certain way, but typically, it was more outright. She. Asked. For. It. I am thinking of this was passed on in our family, in our community, spreading out in concentric circles, ever wider – and ever more tragically.

Lurking under the surface for me is also the specter of how individualism works in these things. When we make it “her” or “their” problem, whether through causation or through how we choose to deal with this on a bigger canvas – how we choose to deal with this as a people.

As a Church we have a greater issue. I can only think of Pope Francis’ recent words about how we respond to a company failing in one way, and how that becomes news, but people starve and not a word is said.

The Fortnight for Freedom is a reminder to me of the misuse of power. By the government? Maybe. By some factions in Catholic culture? Definitely. It is more about self-protection than the protection of others if you ask me. Which brings me right back to the roots of sexual assault and how it happens so frequently and gets treated in the public square.

Thanks for continuing to bring these topics to our attention. I thought you might be interested in the pope’s second prayer intention for worldwide Eucharistic Adoration Day (June 2nd):

Pope Francis’ second intention is: “For those around the world who still suffer slavery and who are victims of war, human trafficking, drug running, and slave labour. For the children and women who are suffering from every type of violence. May their silent scream for help be heard by a vigilant Church so that, gazing upon the crucified Christ, she may not forget the many brothers and sisters who are left at the mercy of violence. Also, for all those who find themselves in economically precarious situations, above all for the unemployed, the elderly, migrants, the homeless, prisoners, and those who experience marginalization. That the Church’s prayer and its active nearness give them comfort and assistance in hope and strength and courage in defending human dignity.”

Thanks! In the chaos of work – I hadn’t had a chance to read anything on the Eucharistic Adoration Day Francis called for – this is fantastic!