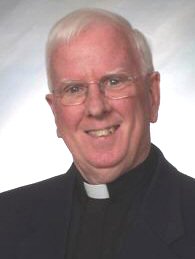

Fr. Robert Nugent died on January 1 at the age of 76. A Salvatorian priest and co-founder of New Ways Ministry, he is well known for his pastoral work with gay and lesbian Catholics and his advocacy on their behalf.

Fr. Robert Nugent authored, edited, or co-edited several important books on a pastoral approach to ministry with gay and lesbian persons in the church including A Challenge to Love: Gay and Lesbian Catholics in the Church (1983), Building Bridges: Gay and Lesbian Reality and the Catholic Church (1992), Voices of Hope: A Collection of Positive Catholic Writings on Gay and Lesbian Issues (1995). Nugent’s early works might seem basic or obvious in the contemporary context, but they were really innovative for their time. One could characterize his moral methodology as trying to build bridges of understanding between church leaders and members of the gay community. His method was interdisciplinary, drawing on psychology, science, and sociology, as well as Scripture and spirituality. Nugent and Gramick founded New Ways Ministry to “promote justice and reconciliation between lesbian and gay Catholics and the wider Catholic community.” In a book written over thirty years ago, Nugent quoted from John Paul II in the dedication page of the book A Challenge to Love:

The Church…is a big community within which there are different situations in the individual communities. There is no lack of people suffering oppression and persecution. In the whole Catholic community, in the individual local churches, there must be an increase in the sense of particular solidarity with these brothers and sisters in the faith… Solidarity means above all a proper understanding and then proper action, not on the basis of what corresponds to the concept of the person offering help, but on the basis of what corresponds to the real needs of the person being helped, and what corresponds to his or her dignity.” (John Paul II, Address to the College of Cardinals, 11/5/1979).

When Fr. Nugent listened to the experiences of gay and lesbian Catholics in the early 1980s, he heard stories of suffering, confusion, exclusion, fear. But he also witnessed joy, friendship, self-sacrifice, and love. He emphasized the inherent dignity of every human person, no matter one’s sexual orientation. In the above quote, we see the emphasis on understanding the suffering person’s story and struggle first, and on acting in solidarity, to offer help on the basis of what corresponds to the real needs of the suffering person and on what corresponds to his or her dignity. In the work of Nugent and others, this means crafting a pastoral theology and sexual ethics that affirms the dignity of all people. To this end, Nugent’s writings offer both descriptive and normative analysis. Take, for example, this important distinction, written in 1983 in an essay, “Priest, Celibate and Gay: You Are Not Alone,” from A Challenge to Love:

A good example of the confusion among Catholics concerning this topic is the common assumption that a homosexual orientation is equivalent to homosexual behavior. Church documents have already endorsed this vital distinction, yet the Catholic public remains, for the most part, unaware of its import… Although official Church counseling for homosexual Christians is celibacy or total sexual abstinence, some Church authorities seem to doubt its possibility. (261-262).

In his essay, Nugent argues that the church needs to understand better the reality of people who identify as gay or lesbian, and that this is true also of the need to better understand and support priests who identify as gay. Nugent writes:

The crux of the seeming impasse between demanding total sexual abstinence from gay Catholics on the one hand, while refusing public acknowledgment of celibate gay clergy on the other, is the fundamental value judgment about homosexuality as an orientation. This basic judgment, whether made individually or communally, has a great impact on the structures and procedures of Church life. Many people are opposed to public disclosures of homosexuality among celibates simply because they disvalue not only homosexual behavior on moral grounds, but they also disvalue the orientation on psychological, social, and other grounds. Despite talk about respect for the dignity of each unique person as the USCC guidelines for sex education (USCC 1981) stress again and again, these people believe that there is basically something wrong, or at least incomplete and lacking, with a homosexual orientation. For them, there is, indeed, something a little “queer” about being gay. They might admit that a homosexual orientation (and all that this notion implies in terms of affectivity, emotional responses, etc.) is part of the individual psychic given; that a homosexual orientation is established (through, as yet, not completely known factors) at a rather early age; that the homosexual orientation is morally neutral. But they are unwilling to concede that this is also socially, biologically, or even psychologically “neutral.” Nor do they believe that a homosexual orientation can fulfill the real meaning of human sexuality in the same way that heterosexuality does. Heterosexuality remains “normative,” and, as Bishop Mugavero has stated, “any other orientation respects less adequately the full spectrum of human relationships” (Mugavero 1976)…. The entire issue of the relationship and dynamics between orientation and behavior needs greater study. We must avoid either confusing them so much that we deny the possibility of celibacy or separating them so much that we render meaningless all talk of the “body-person” and negate the teaching of the Declaration on Sexual Ethics, which states that “the human person is so profoundly affected by sexuality that it must be considered as one of the factors which give to each individual’s life the principal traits that distinguish it (SCDF 1976)…. On the other hand, if one believes that a homosexual orientation contains basically all the humanizing and Christian elements and interpretations of agape (trust, self-sacrifice, vulnerability, loyalty, fidelity, suffering, etc), then one is more comfortable in the face of full and honest affirmations of gay celibates, which can be seen as promoting their human growth and spiritual development. Although this position still fails to throw light on the orientation/behavior discussion, at least it broadens the consideration of homosexuality beyond the area of sexual gymnastics and bedroom sociology. This view also helps people develop their thinking on the full meaning of “orientation” and its implications for one’s stance toward ministry, life, religious experience, faith, prayer, and a host of other issues. (262-265).

Later in this same essay, Nugent writes:

We are finally able to admit that many of the priests who have served as role models of compassion, faithfulness, and dedication are homosexually oriented… If we can begin to create a more trusting atmosphere for the growth of gay clergy and religious in whatever situations they find themselves; if we can give serious study to related issues of chastity and celibacy, intimacy and ministry; if we can provide sound education on homosexuality in all its multiple dimensions, then we might be able to reduce, if not eliminate, some of the pain associated with loneliness, isolation, and tension generated by conflicts of value systems and experiences of life. We can provide strong support systems for gay clergy who struggle for a life of sexual maturity, affective growth and fulfillment, and celibacy for the Kingdom. Their struggles are similar to those of nongay clergy, although the stresses and strains of coping mechanisms differ in some significant ways. If the Church in the next few decades can conquer innate fears and anxieties about homosexuality in general and gay clergy and religious in particular, we can improve the quality of clerical life, enhance the ministerial gifts of many priests, make celibacy itself more credible and compelling, and help other priests… (275).

Many theologians and ministers have followed in Nugent’s footsteps, trying to help the Church “provide sound education on homosexuality” and “conquer innate fears and anxieties about homosexuality.” This has been important not just for gay clergy but for a much wider audience of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgendered people and their allies and family members. But this work is not without risk. Nugent’s most recent book follows a different theme from his life and ministry: Silence Speaks: Teilhard de Chardin, Yves Congar, John Courtney Murray, and Thomas Merton (2011). Nugent knew firsthand the pain of being silenced by the church.

In May of 1999, in a Notification from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (Prefect, Joseph Ratzinger), Fr. Nugent and Sister Jeannine Gramick were accused of promoting ambiguities and errors with regard to official church teaching on the morality of homosexual acts and the homosexual inclination. When pressed by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to provide evidence of assent to official church teachings, Gramick and Nugent provided nuanced answers stating their beliefs. These faith statements were not accepted by the CDF. The Notification explains the problem in this way:

Father Nugent would not sign the declaration he had received and responded by formulating an alternative text which modified the Congregation’s declaration on certain important points. In particular, he would not state that homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered and he added a section which calls into question the definitive and unchangeable nature of Catholic doctrine in this area.

The Notification concludes with this analysis and punishment:

Given the failure of the repeated attempts of the Church’s legitimate authorities to resolve the problems presented by the writings and pastoral activities of the two authors, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith is obliged to declare for the good of the Catholic faithful that the positions advanced by Sister Jeannine Gramick and Father Robert Nugent regarding the intrinsic evil of homosexual acts and the objective disorder of the homosexual inclination are doctrinally unacceptable because they do not faithfully convey the clear and constant teaching of the Catholic Church in this area.3 Father Nugent and Sister Gramick have often stated that they seek, in keeping with the Church’s teaching, to treat homosexual persons “with respect, compassion and sensitivity”. However, the promotion of errors and ambiguities is not consistent with a Christian attitude of true respect and compassion: persons who are struggling with homosexuality no less than any others have the right to receive the authentic teaching of the Church from those who minister to them. The ambiguities and errors of the approach of Father Nugent and Sister Gramick have caused confusion among the Catholic people and have harmed the community of the Church. For these reasons, Sister Jeannine Gramick, SSND, and Father Robert Nugent, SDS, are permanently prohibited from any pastoral work involving homosexual persons and are ineligible, for an undetermined period, for any office in their respective religious institutes.

Gramick and Nugent responded differently to the CDF Notification. Gramick, who is the subject of the documentary In Good Conscience, has remained an outspoken ally of the LGBTQ community. But Nugent complied with the order. He remained a priest and served in parish ministries until his illness. In a recent article about the legacy of Fr. Nugent for the National Catholic Reporter, Megan Fincher interviewed friends of Nugent who described this as a painful journey for him. Mary Linton explained:“He decided to back away from the work, not because he didn’t believe in it or thought he did anything wrong, but because he thought it would show his commitment to the priesthood and the Gospel.” Nugent told Linton, “I have to be a priest. That’s all I’ve ever wanted in my life is to be a priest.” Francis DeBernardo explained, “One of his messages to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered community was that they had to follow their consciences in regards to how to live their lives. [After the censure] they could see that he had to follow his conscience.” David Gentry-Akin explained that Nugent’s “agenda was not to oppose church teaching, but that he wanted “the church to live up to what she says about the dignity of every human person.”

I have seen first-hand the impact of Nugent’s pioneering work in this area of pastoral theology and sexual ethics. In the summer of 2001, in between my two years of study earning an M.T.S. degree at Weston Jesuit School of Theology, I interned in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles Ministry with Lesbian and Gay Catholics. This was an official archdiocesan ministry under Cardinal Mahoney and directed by Fr. Peter Liuzzi, O.Carm, and Marge Mayer. One of the most memorable events of the summer was when we staffed a booth at the LA Pride Festival with a large banner reading “Welcome Home Catholics.”

My job that day was to stand under this banner and talk to anyone who wanted to talk about the Catholic Church. We had brochures to distribute information about discussion groups for gay men, support groups for parents with gay or lesbian children, Mass times at churches known to be gay-friendly, and names of spiritual directors interested in accompanying gay and lesbian people in their journey of faith. We had copies of the USCCB document, Always Our Children, and note cards with the quote: “Though at times you may feel discouraged, hurt, or angry, do not walk away from your families, from the Christian community, from all those who love you. In you God’s love is revealed.”

But my real job was not to pass out brochures, it was to just be there to listen to people and hear their stories. My experiences that summer shaped my approach to theology and pedagogy in a significant way. I heard stories of stigma and rejection, the pain of people who felt abandoned by their faith community. And yet I also witnessed the commitment of some gay Catholics who said they could never leave the Church, that this was their Church too and as much a part of their life and identity as their sexual orientation. Despite the silencing of Fr. Nugent, others have taken up the task of articulating a liberating sexual ethic that affirms the human dignity of the person. One might note similarities between the work of Gramick and Nugent and the writings of Margaret Farley, Patricia Beattie Jung, Charles Curran, Todd Salzman and Michael Lawler, Mary E. Hunt, James F. Keenan, and others. This work will go on, but it is important to stop and remember the risks taken by Fr. Nugent and the impact of his compassionate and sensitive approach to ministry with the gay and lesbian community. I am grateful for his life, work, and tremendous legacy for Catholic ministries. May his soul and all the souls of the faithful departed through the mercy of God rest in peace, Amen.