You should read this book because it will challenge you to think in fresh ways about the goals of theological education, the joys of teaching and mentoring, the difficulties of forming communities among people trained to dissect and deconstruct everything they read, and because it offers a moral vision for a better way to structure our learning and teaching spaces.

After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging, by Willie James Jennings (Eerdmans, 2020), tacks back and forth between prose, poetry, and storytelling to weave together insights into the problems of academic life in the theological academy (divinity schools, seminaries, and theology departments)– problems rendered as both personal and political/social. The use of poetry and narrative provides an opportunity to delve into deeper reflection of key issues that surface in the descriptive analysis. The reader sees how curricular design, racialized power dynamics, hierarchical leadership structures, and the regular vices of greed and self-absorption play out in various spaces for different kinds of agents (with a focus on students and faculty from underrepresented groups).

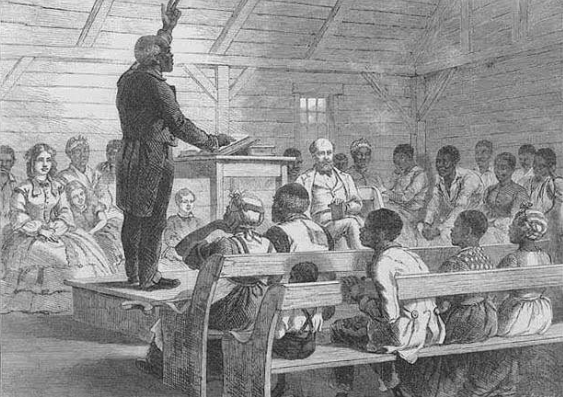

A central claim of the book is that Western educational systems, including seminaries and institutions of higher education, perform whiteness and continue to form faculty, administrators, staff, and students in this “way of being in the world and seeing the world” that perpetuates the control of a master class (though this is often performed and absorbed in subtle ways that become invisible to many). Jennings ultimately argues that “white European masculinist formation” is contrary to the heart of good theological education and that we have a lot of work to do in order to recover what he calls a “pedagogy of belonging” (9-10). A particularly powerful section that reflects on the racial paterfamilias of institutional life can be found in the third chapter. It starts with analysis of a pencil drawing that was published in the Illustrated London News in 1863 with the title “Slaves at Worship on a Plantation in South Carolina.”

Jennings analyzes the posture of the slave master and his family in contrast to the enslaved peoples, showing how church and the violence of colonialism and slavery are interwoven in this image: the social hierarchies deemed ‘natural,’ the enslaved preacher “proclaiming a gospel useful to this institution–church, slavery, whiteness.” (82). Jennings then asks the reader if our theology classrooms today recreate the “pedagogy of the plantation.”

At the heart of the book is a desire to speak truth about the spaces we inhabit, to enter into mutually vulnerable dialogues (without violating appropriate boundaries), and to come together to seek a better way of transforming theological education. It means asking new questions about our telos as theologians and administrators, and from that new vision, thinking anew about admissions, curriculum, funding, mentoring, publishing, liturgy, teaching, and community engagement.

Some of the wisest words are captured in the “secrets” told– combined fragments from various stories. For example, what he was waiting to hear from a bright student in office hours, a student who wanted to go to graduate school:

I was waiting for this: “I have these questions that refuse to let me go–questions about life and death, urgent questions about the why of a world gone mad and of a faith toying with that madness…” (35).

Or another…

“She told me that this would be the last time that she would listen to her heart. Too many disappointments, too many cuts of disrespect into her sensitive soul. She would leave this school, this thorn-crusted place, as soon as another job became open…” (92).

The stories captured throughout the book speak of theology classrooms honestly. Some get it right: in mutual respect and a shared vision, faculty and students unpack and debate big ideas and people change and grow. But seminaries and theology classrooms can also be places of power struggles, toxic shame, arguments without shared purpose or mutual trust, places to prove a point or feel smart by making someone else feel weak. People can be brilliant and simultaneously mean and tone-deaf to their colleagues. Perhaps any work space is like this– but what makes it so hard in a seminary/theology department context is that people’s identity and faith are often tied up in their experiences of the classroom and social world of the seminary/theology department. To feel rejected and demeaned among this group of people can be spiritually devastating. And seen through the lens of the pedagogy of the plantation, one is left wondering how to disrupt and dismantle white power structures that are deemed ‘natural’ within current academic landscapes.

Theological education could mark a new path for Western education, one that builds a vision of education that cultivates the new belonging that this world longs to inhabit. But we cannot give witness to that newness if we imagine that our fundamental struggle is one of institutional survival, or the challenge of educational delivery systems, or the alignment of financial modeling with our desired outcomes, or the expansion of pedagogical models. All these matters are important, but they are not where the struggle meets us or from where the vision of our futures will come.

(After Whiteness, 154).

The shared work of cultivating belonging in the theology academy is a hopeful vision of what our work together could be if each scholar recognizes that they have responsibility for shaping the future not only in their publications but in their service and community building within their institutions. It starts from the simple steps of looking, listening, and talking together. We need to look around us, giving special attention to structural inequities and broken systems and broken souls. We need to listen to one another without trying to fix each other but to hear each other’s stories and share each other’s faith journeys. And we need spaces in which we can talk honestly together about what we can do to mend the systems that are broken.

I wish to thank the Wabash Center for Teaching and Learning for giving me this book and providing the opportunity to discuss it with faculty colleagues in my Digital Salon cohort.