WIS 18:6-9

PS 33:1, 12, 18-19, 20-22

HEB 11:1-2, 8-12

The passages that come to us this week are difficult, on several levels. Our first reading speaks of the Passover: from the vantage point of the Hebrews, an act of liberation; from the vantage point of the Egyptians, an act of destruction. The long version of the epistle reading includes a description of the binding of Isaac, where God asked a child sacrifice of Abraham as a test of faith: one of the hardest biblical passages for moral theologians to account for when we also want to insist on an all-loving God, not just one who is omniscient and omnipotent. And then finally, we have parables that describe God as the owner of slaves, the call for watchful waiting, for vigilance in Luke’s Gospel.

These themes are all the more challenging as we spend this last week lamenting the deaths and injuries that three shooters caused in Gilroy, El Paso, and Dayton. The vigilance of Luke’s gospel rings differently to our ears, today, where slogans like “if you see something, say something” ring out in every space for public transit, where schoolchildren are regularly run through active shooter drills, and where we face the brutal truth that none of those things are sufficient to protect us from violence. I feel this particularly keenly as a woman, as a teacher. Assessing my classrooms for exit routes in the case of an active shooter on campus is not that different from the way I assess where I can park in the daytime so that I can safely return to my car at night, or the anxiety I always felt about the risk of a burglar or home invasion when I lived alone. I have spent a great deal of my life being vigilant about all manner of human harm and violence. Despite that, I am still often fearful of being caught off guard because I just wasn’t careful enough.

I know that Jesus’s words here are parables, and they warn us not of the arrival of human violence (even if they employ that imagery), but the arrival of the end times, the eschaton. Reading between the lines of the violence that pervades these readings, we see stories meant to encourage trust and faith in God. Trust that a marked doorway will save the oldest son, trust that a journey to a new land will beget “descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky,” trust in a reward for the prudent, faithful, vigilant servant. Faith peeks out at us in these words, like the servant peeking through the slots on a shutter. Faith is meant to be the good news that we hear, today: faith will protect you and your loved ones from harm.

And yet, this good news falls on many hollow, hurting hearts – my own included. Sometimes, the good news is not soothing, but a warning. Faith is no magic shield, faith (or lack thereof) is not what determined who lived or died in CA, TX, and OH this week. Human violence does not care how careful you are, how good you are, how much you trust in God. Last week, we heard just how little human prudence matters in the parable of the foolish rich man. The rich man, doing what many of us would do today by seeking to store his goods, rather than give them to the poor, finds his plans derailed by God. Death, we were told, would come for that man that evening, and his prudential planning was for naught. This might seem to contradict Jesus’s call for watchfulness, today. On the one hand, all preparation is for naught; on the other, stand at attention, anticipate the unknown.

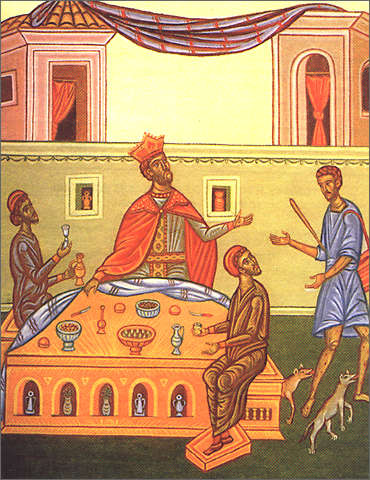

I think part of the difference between these parables is found in a shift in the point of view. Last week, we heard from the wealthy farmer, but this week we see the viewpoint of the slave. The wealthy, the privileged are told their material goods are no armor against death, while the poor are told to prepare themselves against the wrath of the powerful. This is the tension we need to enter, to embrace. Those who seek protection by relying on material objects, by rejecting the needs of the poor will find those efforts to be useless. Those who know they are vulnerable, who tell us plainly their fear of being “hunted” and harmed by the “masters” of this world may be the ones who see most clearly the world that white nationalism has wrought. And it is that sin against which we must direct our vigilance. This runs deeper than unsupervised suitcases in airports: this is vigilance against the very darkest parts of our hearts, our neighbors, and our country. This is vigilance against the language of dehumanization, against policies that deny human dignity, against our own fear and selfishness that would build walls and barns before welcoming the stranger in need to our table.

No, the good news this week is not cheerful, is not soothing; it is demanding: “Much will be required of the person entrusted with much, and still more will be demanded of the person entrusted with more.”