Amos 6:1,4—7

Psalm 146

I Timothy 6:11—16

Luke 16:19—31

Oh, yet we trust that somehow good

Will be the final end of ill,

To pangs of nature, sins of will,

Defects of doubt, and taints of blood;

That nothing walks with aimless feet;

That not one life shall be destroy’d,

Or cast as rubbish to the void,

When God hath made the pile complete;

That not a worm is cloven in vain;

That not a moth with vain desire

Is shrivell’d in a fruitless fire,

Or but subserves another’s gain.

Behold, we know not anything;

I can but trust that good shall fall

At last—far off—at last, to all,

And every winter change to spring.

So runs my dream: but what am I?

An infant crying in the night:

An infant crying for the light:

And with no language but a cry.

Some of you out there might recognize this poem; it is Alfred Lord Tennyson’s In Memoriam, written on the occasion of his dear friend’s death in 1833. Besides being a masterful study in Victorian verse, it is also a profound reflection on our mortal condition. In particular, it highlights the finitude of our knowledge with respect to the ultimate destiny of human life, and creation more broadly. For that reason it is not a particularly uplifting poem, but at the same time I feel it can help pry loose a spiritual space in which one may fruitfully receive the Word of God found in Scripture. Such is especially the case for this Sunday’s lectionary readings.

In these passages we encounter a God who judges. The typical way in which contemporary American Catholics like to soften this unavoidable conclusion is to say that we see in such texts God’s “preferential option for the poor.” And it is undoubtedly true that God’s judgment here is against the rich and on behalf of the poor. Yet there is also something unpredictable and untame about God’s actions here that should make us all uncomfortable. As is so often the case in the Biblical testimony, God’s judgment comes as a surprise to those who are judged, as if the last thing they expected was to find themselves ultimately on the wrong side of divine justice. If we can safely assume that they believed in the reality of such justice, their mistake was to understand it in a false and distorted way. Their fatal shortcoming, in other words, was to presume they knew what God’s judgment would be.

The prophet Amos points directly toward this vice of presumption in the first reading. “Thus says the LORD the God of hosts: Woe to the complacent in Zion! Lying upon beds of ivory, stretched comfortably on their couches… They drink wine from bowls and anoint themselves with the best oils; yet they are not made ill by the collapse of Joseph!” I for one find it incredibly unsettling to hear the prophet speak of God judging Judah not only for her conspicuous consumption and self-satisfaction, but for a lack of proper grief toward the downfall of others. That we are not made ill by the collapse of our brothers and sisters is a criterion for divine judgment! I cannot help but think of Flannery O’Connor’s portrayal of Mrs. Greenleaf, the tenant farmer’s wife whom the respectable Mrs. May finds weeping over the spot of dirt where she had buried all the newspaper clippings detailing the worst of the crimes and calamities in the world.

What do we allow ourselves to weep over when we read of the “collapses” going on in our time and place? What does it say about us if we find that very few of them actually touch us on a human level? It would certainly not do, of course, to contrive such personal reactions; they inevitably depend upon prior dispositions. Yet Amos himself gives us a helpful image by which to consider such a shortcoming: “Improvising to the music of the harp, like David, they devise their own accompaniment.” This description is not just one more picture of decadent insouciance. It describes a state of self-sufficiency: a way of living in which the meaning—the “tonality” if you will—is entirely self-determined and self-directed. Here Amos points to those who “play the music” of their life to their own accompaniment, isolated from the promptings of the Spirit which could lead them to change their melodies.

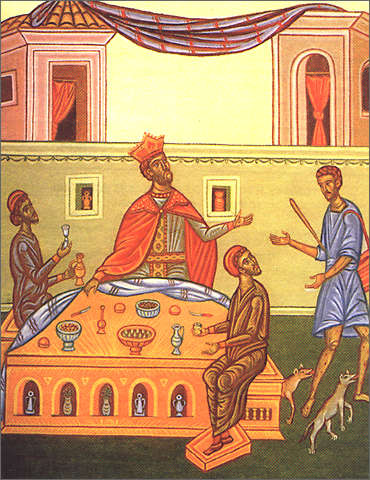

Likewise in the Gospel reading we hear of a nameless rich man who is clearly self-contained, absorbed and consumed by his own affairs, his own “accompaniment.” Before him each day lies the potential encounter which could break him out of his pathological self-satisfaction. Before him each day lies Lazarus, poor and afflicted with sores, simply waiting for the opportunity to eat some of the rich man’s trash. While the rich man is eating the poor man is being eaten, defenseless against the dogs who come to lick his oozing sores. And as happens every day—as it is probably happening right now as I write this—the injustice of this man’s poverty finds no answer, no remedy, no consolation.

The poor man, forgotten in life, is most likely forgotten in death. To expand upon the story, can we not imagine the rich man finally taking action only when he is forced to deal with a rotting corpse at his doorstep? Can we not imagine him doing something about this person only at the point when the person has finally become a thing? Such a scenario is certainly not too outlandish to imagine, nor overly unrealistic even in our own day.

Yet the poor man is not forgotten by God. Lazarus is taken “to the bosom of Abraham.” Notice that his final destination is not designated primarily by the material accommodations Lazarus now receives (the water, in particular) but by proximity to a heart. What matters at the end of this story is that Lazarus is close to the heart of Abraham, and therefore close to the heart of Israel’s God. God does not forget Lazarus; He hears his cry and answers for the unjustice done to him. The rich man, on the other hand, finds himself separated from this justice “by a great chasm”—a place of emptiness and alienation.

The story is suffused with mercy and justice, but also judgment and tragedy. Sometimes I find myself thinking “if only the rich man could just see himself! If only he could have his myopia disturbed for an instant, so that he could see the situation through different eyes!” But there is no happy ending to the story for him. Jesus does not add any throwaway lines at the end, like “but of course, you know, the rich guy will be OK in the end as well.”

The reality to which these readings direct us is a reality that is co-extensive with who God is, meaning that there is no alternative space we could possibly carve out to escape its implications. God is just, but God is also justice itself. Thus to commit injustice is to alienate one’s self from God. That realization should certainly motivate us to act on behalf of the poor: to “become ill” over their collapse and to tend to their needs as they manifest them to us on our doorsteps. Yet that realization should also instill in us a deep humility and a silent receptivity to God’s prophetic Word working in our midst. We can and should have faith “that good shall fall at last—far off—at last, to all, and every winter change to spring.” Yet to participate in God’s justice, and not merely one of our own imagining, is also to recognize that in God’s eyes, we are all “infants crying in the night, crying for the light, and with no language but a cry.”

There is much that I love about this post but I’d be wary of reading a parable, which doesn’t even say that God’s judgment landed the rich man in torment in the netherworld (as opposed to say the rich man’s own moral choice, the consequences of living a life of isolation and selfish greed), as a message of God’s judgement. Pope Benedict said something along these lines which I think is a more helpful approach.

God Bless