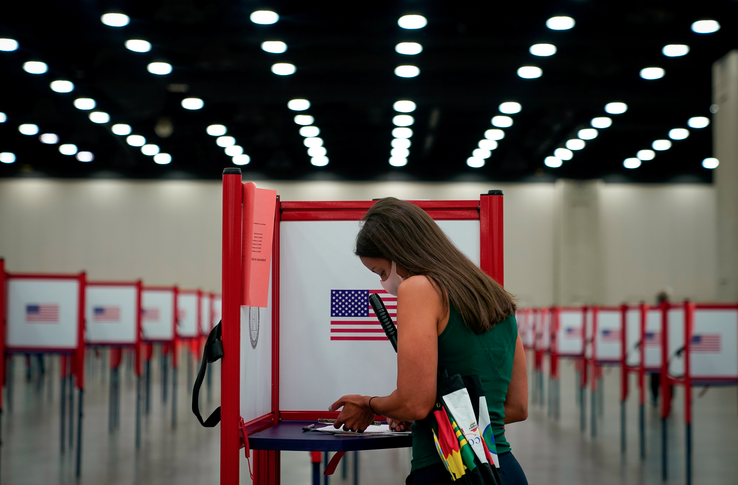

Photo: A young voter in Louisville, Ky., casts her ballot during the Kentucky primary election June 23, 2020, during the coronavirus pandemic. (CNS photo/Bryan Woolston, Reuters)

This is a guest post by Mark Levand, PhD, an adjunct professor in the department of theology and religious studies at Villanova University and in the Center for Human Sexuality Studies at Widener universities. It is the eighth in our Conscience at the Polls series in which CMT bloggers and guest contributors reflect on political participation, conscience formation, and Catholic teachings in advance of the 2020 U.S. presidential election.

There is no question that abortion is “a life issue” for Catholics. There have been several blog posts on this very blog about the complexities and dichotomous nature of this topic, including the role it plays in elections. Adding to this discussion a bit differently, this post is not about the morality of abortion, but rather: what is involved in the morality of single-issue voting on abortion?

We see the condemnation of abortion has led some bishops in the current election year to say that someone is morally compromised if they vote for a candidate who is in favor of legal abortion.

Much attention has been given this year to the USCCB’s document on voting: Forming Consciences on Faithful Citizenship (FCFC). The clear message from this document is that church officials should not be telling people how to vote. On the matter of telling Catholics how to vote, specifically around abortion, Fr. Jim Martin observed that according to FCFC:

“[We] bishops do not intend to tell Catholics for whom or against whom to vote. Our purpose is to help Catholics form their consciences in accordance with God’s truth. We recognize that the responsibility to make choices in political life rests with each individual in light of a properly formed conscience, and that participation goes well beyond casting a vote in a particular election.”

Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship, no. 7.

When we whittle abortion down to a single issue that someone is either for or against, we miss much of the moral complexities that are also relevant to the discussion. In his post, Fr. Martin goes on to mention the moral discourse necessary for considering a candidate that supports the legal status of access to abortion:

“And, for good measure, Pope Benedict XVI (as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, prefect of the CDF, using the language of moral theology) [said]: “When a Catholic does not share a candidate’s stand in favor of abortion and/or euthanasia, but votes for that candidate for other reasons, it is considered remote material cooperation, which can be permitted in the presence of proportionate reasons.”

Martin was citing this memorandum on the CDF’s Doctrinal Note on some questions regarding The Participation of Catholics in Political Life.

In this discussion, it is very clear that magisterial teaching condemns abortion as immoral concerning the dignity of human life. And I’m very sure that Fr. Martin is not arguing that abortion is a moral good. Many faithful Catholics often see the issue of abortion in politics as the single issue that should decide someone’s vote. However, we see the bishops thoroughly condemn the concept of single-issue voting:

“As Catholics, we are not single-issue voters. A candidate’s position on a single issue is not sufficient to guarantee a voter’s support. Yet if a candidate’s position on a single issue promotes an intrinsically evil act, such as legal abortion, redefining marriage in a way that denies its essential meaning, or racist behavior, a voter may legitimately disqualify a candidate from receiving support.”

Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship, no. 42.

It is important to note here that the permission to disqualify a candidate from receiving support is not the same as mandating a Catholic not offer support. The offering of support is an issue of morality and conscience. If voting constitutes engagement in moral life involving our dignified, inviolable consciences, it is important that we inform ourselves about the topic, ensuring we are acting in ‘right view.’ In relation to other issues of life, the hyperfocus on abortion can cause an undermining of the call for the common good. But what about the morality of reducing abortion to a single issue?

When making moral decisions, it is important to have a correct view about what’s going on, while also being mindful about the outcome of our choices.

In moral theology, understanding possible outcomes of our choices—in this case, of voting for someone who would make abortion illegal—is called conceptual knowledge. Moral theologian Richard Gula calls this knowledge “the kind of knowledge we have when we have the right information and have mastered the facts.”[1] In other words, Catholic moral theologian Bill Mattison says “we cannot act rightly if we do not see rightly.”[2] It is relatively easy to see how abortion can cause harm to the unborn—one does not have to dig too deeply into Catholic teaching to find this to be true. But what else must we consider when it comes to the issue of abortion in politics? Because in politics, it is not just the morality of abortion, but also the moral implications for making abortion illegal.

So how do we gather information on this topic? And how do we know what will happen if we make abortion illegal? There are a couple ways to make an educated guess.

It is important to remember that the moral topic at hand is the legalization of abortion, not the act of abortion itself. It is important to make this distinction because many people who are considered “pro-choice” may be personally against abortion but support the legalization of abortion access. This is an important point considering Pope Benedict’s statement on remote material cooperation—if one is supporting a pro-choice candidate, it is important that their reason is not because they view abortion as a good. Most people who support candidates who protect legal access to abortion very likely do not do so because of procedure of abortion, but rather because of the what the legalization protects against.

In countries where abortion is made illegal we see that women are jailed for seeking abortions (which separates families); spontaneous abortions (miscarriages), if not proven to be miscarriages, can be deemed illegal actions resulting in incarceration; expecting parents may be forced to incur funeral expenses for spontaneously aborted fetuses; and perhaps the most important point—making abortions illegal would not necessarily reduce abortions, but force people to seek unsafe ways to induce abortions.

While single-issue voters may feel like they wouldn’t want those laws passed, just those making abortion illegal—it is important to note that they would not have control over the people attempting to pass these types of laws in the US, or people in government with more insidious intentions toward women. And while the bishops suggest abortion is being mischaracterized as an issue of women’s health (FCFC, no. 44), that does not mean there are not people behind this movement in the government intending to do women harm.

In all of this, the Catholic goal is to preserve the dignity of life. If, on this topic, the goal is reducing abortions, how can that be achieved? While there is evidence to suggest that comprehensive sex education and access to contraceptives can decrease abortion, it would require Catholics to measure their moral opposition to contraceptive availability versus their moral opposition to abortions. And while moral discussions must continue based on the best available information, abortion is not a single issue, but is inherently tied to social supports for parents and families (i.e., healthcare, adoption, education, child-care, etc.). These are social issues that the bishops also uphold as a “culture of life” (FCFC, no. 65).

It is important to note that Gula observes in conjunction with conceptual knowledge, people use evaluative knowledge to make moral decisions. This type of knowledge, he says, is more personal than the idea of facts, but the knowledge we gain through sight, touch, and sound—our personal experiences.[3] Through our interdependent nature as humans, gaining knowledge about how the legality of abortion may influence others may impact our moral convictions.

The

morality of voting for a candidate who supports the legalization of abortion or

advocates for the overturning of abortion access is not as simple as ‘making

abortion illegal reduces abortions.’

Making abortion illegal ushers in many other complex moral issues that

people and policies must grapple with in regard to their faith, morality, and

relationship to the human family.

[1] Richard M. Gula, Reason Informed by Faith: Foundations of Catholic Morality (Pulist Press, 1989), 83-87.

[2] William C. Mattison, Introducing Moral Theology: True Happiness and the Virtues (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2008), 96.

[3] Gula, 85.