This is the seventh post in our series, Conscience at the Polls. The goal of the series is to help the discerning voter prayerfully consider the wisdom of our faith tradition when deciding how to vote for particular candidates.

In February, 1976, the United States Catholic Conference (now the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, or USCCB), put forward its first statement on the role of Catholics in the election, Political Responsibility: Reflections on an Election Year. Written in the aftermath of the Vietnam War debacle and the Watergate scandal, Political Responsibility lamented that: “Abuses of power and a lack of governmental accountability have contributed to declining public confidence, despite significant efforts to uncover and redress these problems. Equally important, government has sometimes failed to deal effectively with critical issues which affect the daily lives of its citizens.” In response to these institutional failures and the ensuing apathy and disaffection, the bishops called on U.S. Catholics to fulfill their responsibility as part of “a committed, informed, and involved citizenry to revitalize our political life, to require accountability from our political leaders and governmental institutions, and to achieve the common good.”

In the years that have followed, the bishops’ statements have grown longer, expanding from the 1976 document’s six pages to the fifty-three pages of the current document, Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship: A Call to Political Responsibility from the Catholic Bishops of the United States (FCFC). They have also grown theologically and ethically richer. As I wrote almost exactly four years ago, however, the bishops’ more recent documents have given less attention to the issues of civic participation and government accountability central to the original statement, instead focusing on questions regarding forming the consciences of individual voters and evaluating the stances of competing political candidates in light of Catholic teaching. Although these questions are important, the framing in these more recent documents has narrowed our conversations about Catholic political responsibility in ways that make it difficult for us to adequately address our present moment. For example, as Kathy Lilla Cox explains in her contribution to this series, Catholic citizens must also consider the virtues and leadership qualities of candidates, a consideration briefly mentioned in FCFC. Similarly, at a time when concerns about abuses of power, lack of government accountability, and institutional failure are just as, if not more, salient than they were in 1976, U.S. Catholics must return to the questions of how we can encourage greater civic participation in our political life and strengthen the institutions of democracy.

In his contribution to this series, Michael Jaycox makes the case that our individual consciences are formed in a social context in which we share mutual and communal responsibilities. Jaycox is especially concerned with how our consciences can be malformed by social sins such as racism and how the proper formation of conscience means taking on the responsibility of combatting those social sins. But this insight into the social nature of our consciences also suggests that political participation itself depends on a robust culture of civic engagement and resilient democratic institutions. Four years ago, I argued that our notion of “faithful citizenship” must be expanded to include not just voting but also democratic participation in the life of our communities between elections. In this essay, however, I want to consider how concern for the fragility of our democratic institutions ought to factor into our voting decisions this year. After all, what does it mean to exercise the virtue of prudence at the ballot box in a situation where citizens’ right to vote in free and fair elections is being eroded? How do voters promote the values central to Catholic social teaching when political leaders abuse their power for personal benefit and weaken the instruments of public accountability?

Catholic Social Teaching and Democratic Institutions

Although FCFC sidesteps these questions, Catholic social teaching offers us resources to help us address them. It is commonly stated that the Catholic Church accepts a variety of different types of regimes as long as they promote the common good, but since the Second World War the Church’s Magisterium has increasingly recognized that the common good is best realized through the participation of the citizenry in democratic institutions (see here for historical citations). The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church defines participation as “a series of activities by means of which the citizen, either as an individual or in association with others, whether directly or through representation, contributes to the cultural, economic, political and social life of the civil community to which he [sic] belongs,” and adds, “Participation is a duty to be fulfilled consciously by all, with responsibility and with a view to the common good.” Although the value of participation is not limited to political life, citizens must certainly be empowered to participate in the governance of society. The Compendium goes on to clearly state: “Although this right is operative in every State and in every kind of political regime, a democratic form of government, due to its procedures for verification, allows and guarantees its fullest application.”

Catholic teaching, as expressed in the Compendium, also recognizes the dangers of corruption and the abuse of power by political leaders, even in democratic governments. For example, the Compendium states, “Among the deformities of the democratic system, political corruption is one of the most serious because it betrays at one and the same time both moral principles and the norms of social justice.” Corruption is not just a betrayal of an official’s responsibilities, but also undermines people’s trust in the democratic system and the culture of civic engagement it needs to function. Much like Cox argues in her essay, the Compendium states that just governance requires political representatives to exercise the civic virtues.

Although not well-developed, Catholic teaching has also recognized the importance of concepts such as the balance of powers and the rule of law for preserving democratic institutions and preventing corruption and the abuse of power. For example, the Compendium cites Pope John Paul II’s statement in his 1991 encyclical Centesimus Annus that, “i[I]t is preferable that each power be balanced by other powers and by other spheres of responsibility which keep it within proper bounds.” John Paul goes on to explain that this balance of powers helps ensure that political authorities are bound by the rule of law and liberties are protected. The Compendium also makes clear the important role that free and fair elections play in preventing abuses of power and holding political leaders accountable.

Catholic Conscience and the Crisis of Democratic Institutions

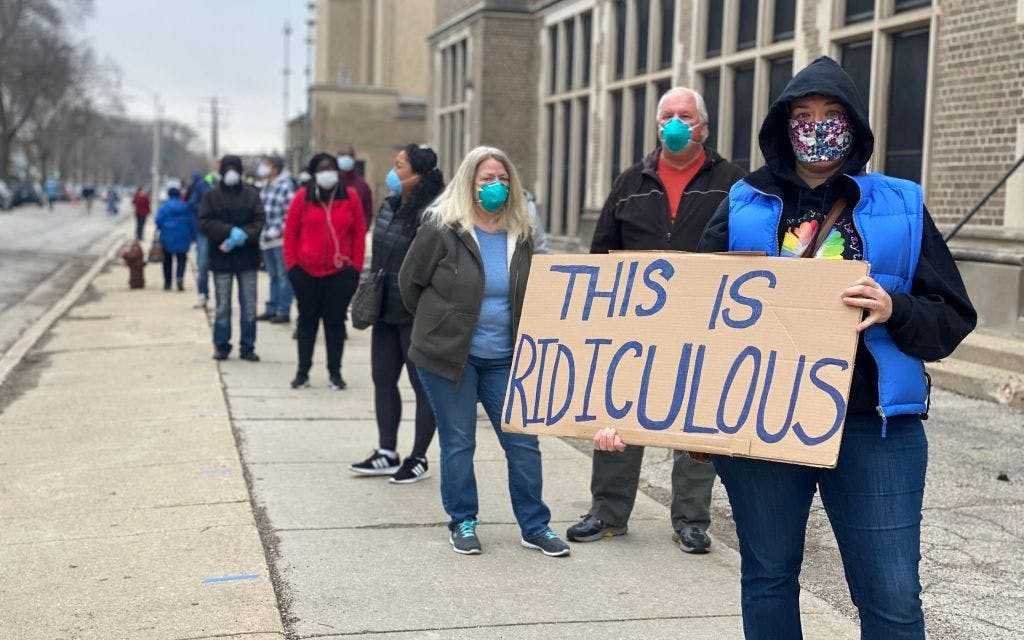

Today Americans confront a crisis of institutional failure, abuse of power, and increasingly fragile democratic institutions at least as serious as that faced by the nation in 1976. In this essay I will focus in particular on the erosion of voting rights, but America’s democratic institutions are also taxed by an executive branch that openly abuses its power and subverts accountability. The COVID-19 outbreak poses an unprecedented challenge to election officials. During primaries earlier this year, voters in states like Wisconsin and Nevada were expected to wait in long, crowded lines before voting, potentially exposing them to the virus. In response, most states have implemented mail-in voting or expanded the options for absentee voting, but the unprecedented numbers of mail-in ballots will almost certainly tax election officials and delay the counting of ballots. Rather than harness the resources of the federal government to help local officials meet these challenges in a fair, transparent, and efficient way, President Donald Trump has promoted implausible conspiracies that his political opponents will use mail-in voting to commit widespread voter fraud, casting the election results into doubt. In the past, President Trump has similarly invented conspiracies about fraudulent voting by immigrants in California and voters bussed from Massachusetts to New Hampshire to call into question the popular vote tally from 2016.

President Trump’s efforts to undermine trust in the integrity of the elections comes on top of efforts by state governors and other state officials, mostly Republican, to purge voter rolls. Although it is necessary to remove deceased voters and voters who have moved to other states from the rolls, these aggressive efforts have resulted in removing legitimate voters from the rolls, taking away their right to vote. For example, in 2019 Texas Secretary of State David Whitley produced a list of 100,000 registered voters he claimed based on state records were not citizens, but county officials found that most were naturalized citizens. Earlier this year, the American Civil Liberties Union alleged that in a massive purge of over 300,000 voters, the State of Georgia had wrongly removed nearly 200,000 legitimate voters (the errors committed by the state are truly shocking). Whatever their intentions, these aggressive efforts to purge voter rolls violate people’s civil rights and disproportionately impact low income voters, African-Americans, naturalized citizens, the elderly, and young voters.

After Florida voters passed a constitutional amendment restoring voting rights to citizens convicted of felonies, Governor Ron DeSantis and the Republican state legislature passed a law requiring former felons to pay all fines and other debts associated with their sentences before being eligible to vote, despite the state having no centralized system to let them know what they owe or if they are eligible to vote. Former felons attempting to register and vote potentially face charges of voter fraud if they are found to owe fines they had no way of knowing about.

State and local officials have also made it more difficult for citizens to vote by decreasing the number of polling locations. For example, last year the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights found that since 2013, a number of states in the South and Southwest had closed nearly 1,200 polling places, often in pre-dominantly low income or African-American counties. More recently, Governor Greg Abbott of Texas has prohibited counties from setting up more than one drop off location for absentee ballots for voters concerned about problems with the US Postal Service. Closing or restricting polling locations makes it more difficult for voters to head to the polls, particularly rural voters and voters who lack means of transportation or whose work or family schedules do not afford them much time to travel to the polls.

Considering the Catholic Church’s teaching on political participation and democratic institutions, these challenges to the voting rights of American citizens should be top concerns for Catholic voters in 2020, but they hardly fit into the framework provided by the US bishops in FCFC. Likewise, Catholic voters should be concerned with the unprecedented corruption and abuse of power carried out by the Trump administration. President Trump has refused to separate his private business interests from his public role as president, advertising his properties, spending public money on weekend travel to his golf courses, and engaging in political activities with his adult children who are ostensibly running the family business in his name. The New York Attorney General dissolved Trump’s charitable foundation for coordinating with his political campaign and other forms of corruption, and the president is currently being investigated by the Manhattan district attorney for tax fraud. Numerous cabinet and other administration officials have engaged in corruption of their own. President Trump has also abused his powers, calling for the investigation of his political opponents and, according to the Mueller Report, using the powers of the presidency to hinder the FBI’s investigation of his campaign’s relationship with Russians engaged in interfering in the 2016 election. The Trump administration has stonewalled congressional oversight on a host of issues and dismissed inspectors general investigating corruption or other misconduct. The president has declared flimsily-justified national emergencies to circumvent Congress and fund pet political projects like the border wall and, allegedly, offered pardons to Customs and Border Protection agents who broke the law in preventing asylum seekers from entering the country. These scandals should weigh heavily on the conscience of any responsible Catholic voter, but they hardly fit into the issue-by-issue approach laid out in FCFC.

At the same time, the powers of the executive branch have expanded under presidents of both parties, weakening democratic accountability and congressional oversight and paving the way for the abuses listed above. Vice presidential candidate Kamala Harris has in the past expressed no qualms about using some of the same executive powers as President Trump, for example advocating for an executive order on gun control. After the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett for the position, Democrats are seriously considering the possibility of adding seats to the Supreme Court, raising serious questions about the role of the Supreme Court in checking congressional and presidential power. Wherever one stands on these issues, the health of the United States’ democratic institutions is in a fragile state, a problem that has been developing for a long time and that is larger than Donald Trump. Unfortunately, the narrow framing of electoral issues in FCFC makes it difficult for U.S. Catholics to faithfully address this challenge. As I have tried to explain in this essay, however, the resources exist in Catholic teaching to help guide Catholic voters in assessing how to think through these challenges as we head to the polls even if they do not provide us with easy answers.