“The Church wishes to help form consciences in political life and to stimulate greater insight into the authentic requirements of justice as well as greater readiness to act accordingly, even when this might involve conflict with situations of personal interest. Building a just social and civil order, wherein each person receives what is his or her due, is an essential task which every generation must take up anew.” -Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est, no. 28.

“An authentic faith… always involves a deep desire to change the world, to transmit values, to leave this earth somehow better than we found it.” -Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, 183.

Introduction

Catholic teaching is clear that the goal of politics is justice. We are social creatures by nature and flourish in communities. But in a context of increased polarization and partisanship, the task of political engagement can seem far from a holy act of discipleship. We often associate politics with entrenched positions, messy debates, dark money, and dishonesty. How can we recover a virtuous practice of political participation with the common good as our telos?

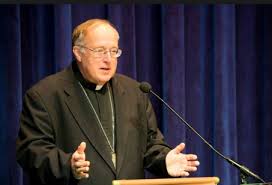

In a thoughtful and pastorally sensitive speech tonight at the University of San Diego, Bishop Robert W. McElroy of the Diocese of San Diego delivered an address entitled “Conscience, Candidates, and Discipleship in Voting,” in which he offered the faithful practical guidance for thinking about voting as an act of discipleship. He started by affirming that Catholics participate in “the just ordering of society and the state” primarily through their voting rooted in conscience. Called to be “missionaries of dialogue and civility,” faithful voters need tools to understand the range of issues addressed in Catholic social teachings, skills in discernment, and the virtue of prudence.

Overview of the Talk

The first big section of the talk explained that the faithful voter should not be a single-issue voter. Bishop McElroy named “ten salient goals” that emerge from the Gospel and the tradition:

- The promotion of a culture and legal structures that protect the life of unborn children.

- The reversal of the climate change that threatens the future of humanity and particularly devastates the poor and the marginalized.

- Policies that safeguard the rights of immigrants and refugees in a moment of great intolerance.

- Laws that protect the aged, the ill, and the disabled from the lure and the scourge of euthanasia and assisted suicide.

- Vigorous opposition to racism in every form, both through cultural transformation and legal structures.

- The provision of work and the protection of workers’ rights across America.

- Systematic efforts to fight poverty and egregious inequalities of wealth.

- Policies that promote marriage and family, which are so essential for society.

- Substantial movement toward universal nuclear disarmament.

- The protection of religious liberty.

He explained that this is not a ranked list; none of these has preeminence. All must be addressed. He went on to say that the current “culture of exclusion” must be repudiated.

The next section of the talk focused on the candidates on the ballot. In deciding how to vote, one must consider the opportunity the candidate will have to advance the common good; the competence of the candidates; and the character of the candidates.

The final section of the talk builds a robust understanding of prudence. Prudential judgment is not a “lesser” kind of reasoning but is properly understood as the virtue by which we confront ethically complex problems.

Analysis and Questions

There is much to praise in this address. Bishop McElroy took on a divisive topic with a balanced and intellectually rigorous approach. He did not give easy or simplistic answers to complex problems but invited people to consider how their faith should influence their voting habits.

The critique of single-issue politics is of particular interest to me. Last summer I gave an address in which I described the USCCB’s Pastoral Plan for Pro-Life Activities as a grassroots mobilization against abortion that initiated a single-issue approach to election politics, an approach that has aligned the USCCB with the GOP in unproductive ways. I was deeply distressed to see President Trump invited to speak at the 2020 March for Life and questioned afterwards whether I should even call myself pro-life anymore. In this context, Bishop McElroy’s address is an important challenge to his brother bishops who continue to assert the priority of abortion and encourage Catholics to vote for candidates on the basis of that policy position alone.

At the same time, I want to encourage bishops, when discussing abortion, to do so recognizing the complexity and ambiguity of that issue itself. In Bishop McElroy’s address, the paragraph advocating for legal protections for unborn children does not even mention once the reality of the pregnant women carrying those unborn children. The women are invisible. We can do better. But it will take crafting a discourse about reproductive justice that speaks to the concrete reality of women facing unplanned or difficult pregnancies. If we continue to talk about “abortion” as an abstract political football that we toss around, we won’t get very far.

I asked Bishop McElroy in the Q&A if proportionalism is making a comeback. I did so because I was encouraged by his analysis of moral gravity as a component of our decision making when choosing candidates. It seemed to me that he was adopting language of weighing values and disvalues in the discernment prior to a prudential judgment; this is the realm of proportionalism. For example, he said

“While the criterion of intrinsic evil identifies specific human acts that can never be justified, this criterion is not a measure of the relative gravity of the evil in particular human or political actions… It is a far greater moral evil for our country to abandon the Paris Climate Accord than to provide contraceptives in federal health centers.”

There is a lot going on in this section and I need to give more thought to it. But I am encouraged by rejection of a simplistic, deductive application of “intrinsically evil acts” to political discussions when what is at stake so often involves complex policy questions that require attention to negotiations of the rights of multiple stakeholders.

The Church doesn’t tell Catholics how to vote in the sense of which candidates to vote for; but this address does tell Catholics how to vote in the sense of what moral guideposts should be given special attention and how the candidate’s opportunity, competence, and character should shape a voter’s decision. Voting is part of the way that Christian disciples “leave this earth somehow better than we found it.” I hope we have strong candidates from which to choose the next time we get to the ballot box.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks