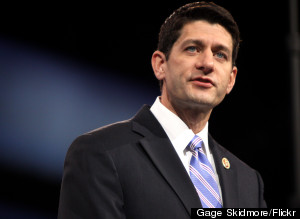

Paul Ryan’s comments on poverty have again set off a swirl of controversy. Though first reported March 12 and clarified the next day, the arguments about what he said continue, in Mother Jones here and here, in the National Review and the Wall Street Journal, and The Atlantic. The crux of the disagreement is about how we answer the questions, “Why are people poor?” and “How can we decrease the poverty rate?” Ta-Nehisi Coates made a compelling case against Ryan:

There is no evidence that black people are less responsible, less moral, or less upstanding in their dealings with America nor with themselves. But there is overwhelming evidence that America is irresponsible, immoral, and unconscionable in its dealings with black people and with itself. Urging African-Americans to become superhuman is great advice if you are concerned with creating extraordinary individuals. It is terrible advice if you are concerned with creating an equitable society. The black freedom struggle is not about raising a race of hyper-moral super-humans. It is about all people garnering the right to live like the normal humans they are.

George Will, and other conservatives, argued that government programs have often done more harm than good, declining male employment is a real issue, and family breakdown among the poor is widespread, so everyone should acknowledge the “possibility that the decisive factors are not economic but cultural — habits, mores, customs.”

While acknowledging the huge gulf between these two schools of thought, I would like to suggest five potential common ground statements informed by Catholic Social Teaching that may help us make our way toward fruitful dialogue rather than “debunking” wars.

1. As Christians, our first duty in the face of poverty is to help rather than to blame.

“Each individual Christian and every community is called to be an instrument of God for the liberation and promotion of the poor, and for enabling them to be fully a part of society. This demands that we be docile and attentive to the cry of the poor and to come to their aid” (Evangelii Gaudium, 187). The Christian tradition has always emphasized the duties of the giver rather than the worthiness of the needy (Matt. 25: 31-46).

2. Poverty results from many interlocking social structures, cultural norms, and personal choices. Reducing it will require personal, cultural, and social change.

Pope Francis writes about the effects of “an economy of inequality and exclusion, ” the “sacraliz[ation] of the free market,” the “culture of prosperity [that] deadens us,” and “lifestyle[s] which exclude others” (Evangelii Gaudium, 53, 54). Without neglecting the need for social reform, he mourns the “practical relativism” at work when people commonly are “acting as if God did not exist, making decisions as if the poor did not exist,” (EG, 80). He talks about “convictions and habits of solidarity, when they are put into practice, open the way to other structural transformations and make them possible” (EG, 189). Our beliefs and practices prepare us to work for social change or to go on ignoring social sin. We cannot disentangle the personal, cultural, and social for the better-off or the needy.

3. Because there are strong associations between poverty and less-than-full employment, those who want to reduce poverty should work together to increase job readiness, job opportunities, and wages.

In an article entitled, “Intragenerational Income Mobility: Poverty Dynamics in Industrial Societies,” the authors conclude that “poverty exits” in the U.S. are most closely associated with increases in the number of persons in a household who work, an increase in the number of months worked, and an increase in earnings. The loss of solid blue collar jobs has made it more difficult for men and women to support their families. The declining value of the minimum wage means that work no longer provides what it once did. Many people in poor neighborhoods defy the odds and make it to work every day, year after year, anyway. Others may internalize the low self-worth assigned to them by the “economy of inequality and exclusion.” Some need classes to help them regain confidence, adopt habits, and develop skills necessary to get and retain a job. The People First program developed by Midtown Catholic Charities in St. Louis is just one of many programs that attempt to fill this need. We can find ways to support these kinds of programs without insulting people or ignoring the reality of the working poor as Ryan seemed to do in his initial comments.

4. Because there are strong associations between poverty and single-parent families, efforts to strengthen marriages and relationships in which children are involved should be supported.

Liberals and conservatives generally disagree about whether poverty or family disruption comes first. Liberals think of family breakdown as a problem that requires an economic solution, whereas conservatives see family formation as a cause of poverty that needs to be addressed directly. But some thinkers from both camps are convinced that efforts to encourage strong marriages and relationships, discourage child bearing outside marriage, and prevent divorce may be warranted. The more we know about single mothers and single fathers, the better we’ll be able to respond to the real obstacles to enduring marriages and strong families as well as celebrate the undeniable strengths of diverse families who thrive against the odds. This stress on families is in keeping with the idea of the family as the first cell of society.

5. While never minimizing the structural causes of poverty, including ongoing racism, we have to find ways to empower those with few options.

New York Times columnist Charles Blow criticized Ryan’s recent comments:

By suggesting that laziness is more concentrated among the poor, inner city or not, we shift our moral obligation to deal forthrightly with poverty. When we insinuate that poverty is the outgrowth of stunted culture, that it is almost always invited and never inflicted, we avert the gaze from the structural features that help maintain and perpetuate poverty — discrimination, mass incarceration, low wages, educational inequities — while simultaneously degrading and dehumanizing those who find themselves trapped by it.

Nonetheless, Blow affirms that even though poverty is primarily a structural problem, getting out requires personal transformation. In a column entitled, “For Some Folks, Life Is a Hill,” he writes that while it’s not fair that some are born into poverty, climbing is the only real option: “You may be born at the bottom, but the bottom was not born in you. You have it within you to be better than you were, to make more of your life than was given to you by life.” We cannot expect people to be superhuman, but those who are farther up the hill can put some energy into empowering the climbing of those closer to the bottom. We can also recognize that, in Christian terms, no one is on the top of the hill, no one gets to the top alone, and all of us need each other along the way.

I will agree with my conservative friends that it is not direct social assistance programs that best help the (non-elderly) poor live decent lives. These programs are helpful in keeping body and soul together while hopefully some outside force helps permanently bring them out of poverty. That outside force is almost always personal interaction with someone who guides them in a new path to self-sufficiency. But here is where the conservatives fall down. That personal interaction rarely comes from some college educated upper middle class successful person. With some rare exceptions, this element’s generosity mostly comes in the form of writing checks to various charities. The personal interaction most often comes from a friend, relative or neighbor with a secure, stable job that delivers regular hours and decent benefits – almost always a union or government job or a pensioned retiree from such a position. The conservative attacks on unions and public workers have decreased the likelihood that a struggling person would have such a neighbor, friend or relative. And the conservative elites have not exactly been known to willingly live among the working poor. Liberals are not all that much better save some progressive religious fanatics like the JVC (I say religious fanatics in a loving way!) and a larger number of young liberals who result in being too large (I offer the cases of Williamsburg NY and Columbia Heights, DC).