A mom whom I respect very much recently told me about an incident with her teenage son. Her son, rather uncharacteristically (he is a good kid) was lashing out at her, spitting out the most awful invectives, screaming “I hate you” over and over again. She tried to reason with him in a calm voice but his anger only intensified. “So I just grabbed him and held him as tight as I could, not saying a word, while he screamed. And after a while, he started crying. He was crying like a baby in my arms. It was awful, but the only way to respond to that much anger is to take it until it disappears.”

I thought of this story as I worked through the readings for Palm Sunday. I’ve never noticed the prominence of the theme of non-resistance to evil.

The theme is introduced in our first reading:

I have not rebelled,

have not turned back.

I gave my back to those who beat me,

my cheeks to those who plucked my beard;

my face I did not shield

from buffets and spitting. . .I have set my face like flint,

knowing that I shall not be put to shame.

The theme continues in the gospel, both explicitly and implicitly. For example, when Peter tries to defend Jesus with the sword, we read,

Then Jesus said to him,

“Put your sword back into its sheath,

for all who take the sword will perish by the sword.

Jesus’ non-resistance is seen at the table of the last supper where he refuses to defend himself against Judas, before Pilate when he refuses to defend himself, in front of the crowds who cry for Barabbas, and on the cross while he suffered innocently, the cruel cry of mockery his only consolation.

Why doesn’t Jesus do something to defend himself, to respond to his attackers? The answer might be seen in part in the answer my friend gave: the only way to respond to such awful anger, such intense violence, was to accept it.

Morally, this answer creates problems. When non-resistance is embraced as normative, it can make us negligent in our responsibility to work for justice, to defend the innocent and vulnerable. Women who are being abused by their husbands, or children by their parents, or students by their teachers do not need to hear to “take it.” But then again, we don’t want resistance, even proportionate resistance, to become normative either. The witness of the cross, of the suffering servant is too powerful. One critical task in the Christian moral life is to determine when non-resistance, when the way of the cross, is most appropriate.

Fights with loved ones often provide such opportunities. When a loved one lashes out in anger, especially uncharacteristic anger, often this is coming from a place of fear or hurt. Responding with anger or injury often serves to exacerbate the situation, not resolve it. Refusing to respond or to resist can can help to resolve the situation by refusing to perpetuate the cycle of anger and violence.

Other opportunities present themselves online, especially with social media. Why is it that people feel comfortable hurling insults or unfriendly criticism online in a way that they would never do in person? It is tempting to respond but often this does more harm than good. Sometimes non-resistance is the best way to undermine the violence and meanness of an angry Facebook or blog comment.

For the Christian, the key to such moments of non-resistance is not to ignore the injustice, but rather to place our hope in God to resolve what we know we cannot.

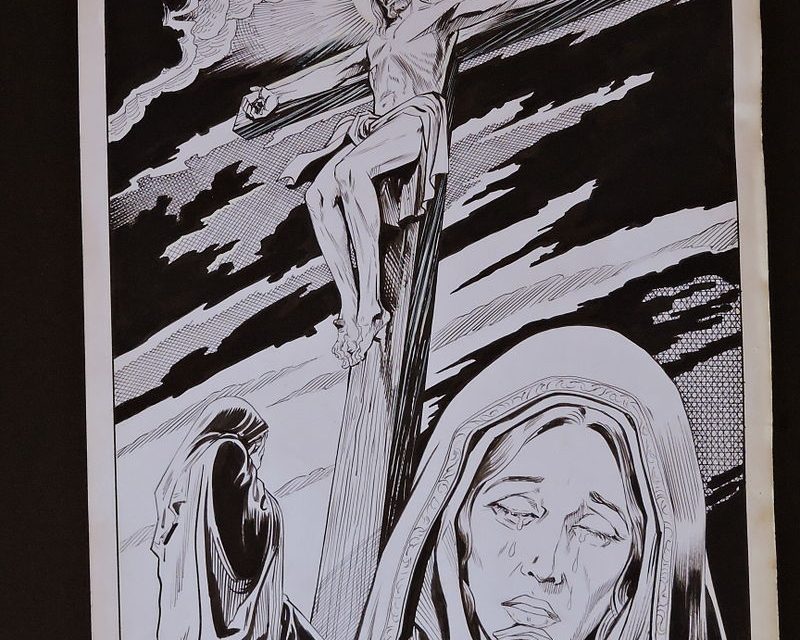

The great spirituality writer Ronald Rolheiser uses Mary under the cross as another example of appropriate non-resistance. In his book Sacred Fire, he writes

In essence, what Mary was doing under the cross was this: her silence and strength were speaking these worlds: “today, I can’t stop the crucifixion; nobody can. Sometimes darkness will have its hour. But I can stop some of the hatred, bitterness, jealousy, and heartlessness that caused it—by refusing to give it back ii kind, by transforming negativity rather than retransmitting it, by swallowing hard in silence and eating the bitterness rather than giving it back in kind.”

Had Mary, in emotional and moral outrage, began to cream hysterically, shout angrily at those crucifying Jesus, or physically tried to attack someone as he was driving the nails into Jesus’ hands, she would have been caught up in the same kind of energy as everyone else, replicating the very anger and bitterness that caused the crucifixion. What Mary was doing under the cross, her silence and seeming unwillingness to protest notwithstanding, was radiating all that is antithetical to crucifixion: gentleness, understanding, forgiveness, peace, light, and courage.

May we have the grace to have the prudence to know when also to not respond in kind.