Let us build a house where love can dwell and all can safely live, a place where saints and children tell how hearts learn to forgive. Built of hopes and dreams and visions, rock of faith and vault of grace; here the love of Christ shall end divisions. All are welcome, all are welcome, all are welcome in this place.

Marty Haugen’s All Are Welcome is one of my favorite hymns to sing at Mass. It presents a vision of an inclusive church community where prophets speak, where peace and justice meet, where the outcast and the stranger bear the image of God’s face, and where love is found. But are we living up to this vision of church?

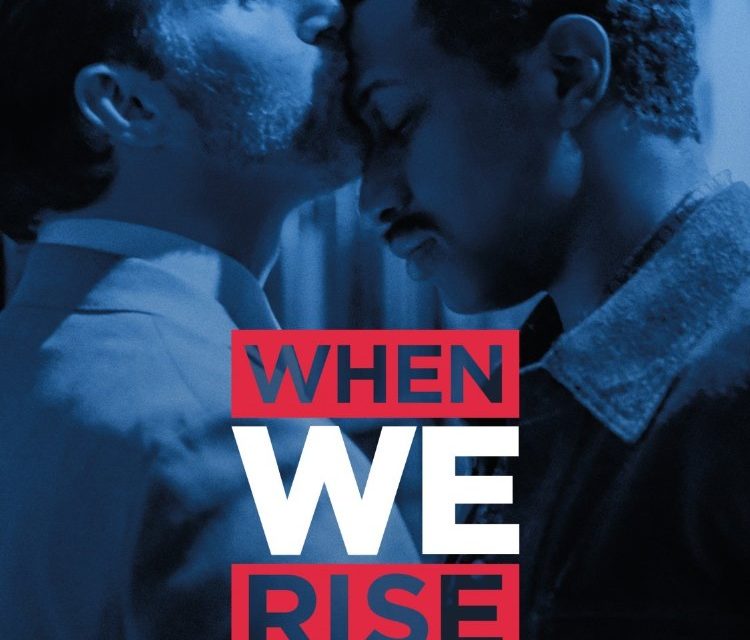

The ABC mini series When We Rise tells the story of the LGBT community in the US from 1971-2015, focusing on four main figures: Cleve Jones, Roma Guy, Diane Jones, and Ken Jones. The first episode aired February 27th. From the beginning the series frames the story of the LGBT community as a civil rights struggle, drawing explicit connections between the anti-Vietnam war peace movement, feminism, and black resistance to racial injustice after Jim Crow. We see Roma and Diane fall in love while serving in the Peace Corps, and we see Cleve’s first activism in the peace movement. We see how Ken continues to face discrimination because of the color of his skin. As their stories unfold, we witness the confusion among family members as young people disclose their sexual orientation, and see the courage it takes young gay and lesbian protagonists to be honest with their family members. They face terrible choices of covering up their authentic identities to avoid rocking the boat, or disclosing their sexual orientation when family members might decide to withhold love and affection. I don’t know what decision I would have made. It is so different from my experience as a cisgender heterosexual woman, and yet as a viewer I can connect on a human level with their yearning for community and their desire for respect and love. San Francisco beckons– but that hub of safety is not without risk. First, there is the physical threat and bullying from young men influenced by hypermasculinity and homophobia; then HIV takes a toll. Gay men buried friends and lovers while politicians refused to acknowledge “gay cancer” and the CDC remained underfunded. The series is able to tell the big story by following these particular characters and their own growth and development over time. In the end, the marriage equality movement is celebrated as victory after decades of activism and struggle on behalf of so many.

As I watched, I kept asking myself where my church was in the midst of these struggles. I didn’t always like the answer I found. My church’s teachings describe homosexuality as “objective disorder” and describe same sex marriage as contrary to the natural law. This language is painful for many young LGBT Christians and those early wounds in Christian communities led many to associate the church with condemnation, fear, and shame. My church has funded lobbying efforts against marriage equality. Even though we know the public health benefits of monogamy and commitment (especially in the wake of HIV), this alone has not been persuasive enough to challenge the heterosexism of church teachings on marriage, at least not yet.

As I watched, I kept asking myself where my church was in the midst of these struggles. I didn’t always like the answer I found. My church’s teachings describe homosexuality as “objective disorder” and describe same sex marriage as contrary to the natural law. This language is painful for many young LGBT Christians and those early wounds in Christian communities led many to associate the church with condemnation, fear, and shame. My church has funded lobbying efforts against marriage equality. Even though we know the public health benefits of monogamy and commitment (especially in the wake of HIV), this alone has not been persuasive enough to challenge the heterosexism of church teachings on marriage, at least not yet.

I know that many Catholic families have supported LGBT family members. And some parishes, like Most Holy Redeemer parish in the Castro, became inclusive and supporting faith communities. Donal Godfrey, author of Gays and Grays, tells the story of Most Holy Redeemer parish, “a spiritual home to all.” But as I watched When We Rise, I kept wondering how my church could have done more.

I know that many Catholic families have supported LGBT family members. And some parishes, like Most Holy Redeemer parish in the Castro, became inclusive and supporting faith communities. Donal Godfrey, author of Gays and Grays, tells the story of Most Holy Redeemer parish, “a spiritual home to all.” But as I watched When We Rise, I kept wondering how my church could have done more.

In Amoris Laetitia, Pope Francis begins chapter 2, the section on “the experiences and challenges of families,” by saying “we do well to focus on concrete realities.” Viewers of When We Rise will be immersed in those concrete realities. And they raise fruitful questions for us still.

On the one hand, we need to acknowledge how, for so many people, families are the locus of trauma. For many young gay men in San Francisco in the 1980s, the gay community became a more pure experience of ‘family’ than their biological families. Have we really learned from this? Do we hold up one idealistic image of family– say ‘the holy family’– and stigmatize blended families, LGBT families, or single parent households, all in the name of ‘family values’? Pope Francis reminded the Synod fathers in his final address that the true defenders of doctrine are those who uphold the spirit not the letter of the law, saying:

The Synod experience also made us better realize that the true defenders of doctrine are not those who uphold its letter, but its spirit; not ideas but people; not formulae but the gratuitousness of God’s love and forgiveness. This is in no way to detract from the importance of formulae–they are necessary–or from the importance of laws and divine commandments, but rather to exalt the greatness of the true God, who does not treat us according to our merits or even according to our works but solely according to the boundless generosity of his mercy. (October 2015, Address at conclusion of Synod in Rome).

What does it mean, then, to privilege people over ideas? I think it means that we do our best to listen and to understand someone else’s story. Sometimes film and television can help us in this, especially when we encounter stories that open us up to new ways of seeing the world or new ways of looking at the human condition. Sometimes it can foster empathy and solidarity–that virtue described by John Paul II not as a vague feeling of pity but rather as a lived commitment to the common good of all. Pope Francis has said that there should be “continued open discussion” and that Christians cannot “bury our heads in the sand.” Of course this is all very difficult. Other take-aways from Amoris Laetitia that might resonate include the emphasis on conscience, the importance of graduality, and the priority of love.

Marty Haugen sings about the love of Christ that can heal all divisions. As we near Palm Sunday, I will be thinking especially of the suffering of the LGBT community as I hear the gospel account of Jesus’s suffering and death. But on Easter morning, I will be joining some of them in the Castro to celebrate the new life we have in Christ, and the hope I have that Christ’s love can help us overcome all divisions and work to transform society so that all may be free and whole.