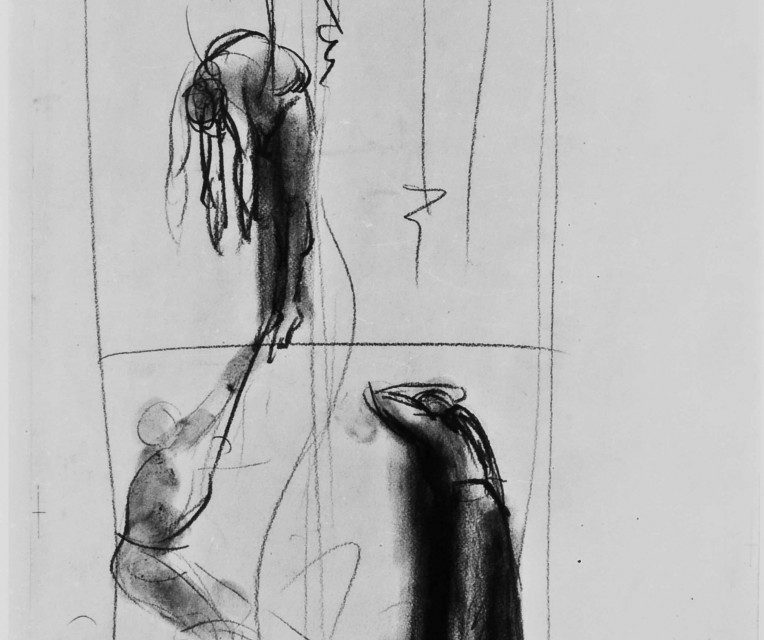

The is a guest post from Miguel J. Romero. Mary Jo Iozzio and he edited the special issue of the Journal of Moral Theology: Engaging Disability. Image is Giacomo Manzù’s “Studio per Cristo in Croce,” and is courtesy of L’Archivio della Fondazione Giacomo Manzù.

“Professor, how does that moral principle work when we’re physically or cognitively impaired…or mentally ill…or somehow disabled?”

It may only happen two or three times each academic year, but every university and seminary level moral theology instructor has experienced being pressed by a student to engage the topic of “disability.” What do you say? The way Catholic moral theologians engage disability, in our teaching and research, is the topic of the new special issue from the Journal of Moral Theology: Engaging Disability, edited by myself and Mary Jo Iozzio.

Every moral theology instructor will agree that an honest, on-topic theological question deserves an intelligent and thoughtful, on-topic response. When the question is about “disability,” however, most contemporary moral theologians are unsure of where to begin and few of us are satisfied with our standard response. Sorting out why we feel dissatisfied with the way we engage disability in the classroom will help moral theology instructors respond to a common student question—and, I believe, can reveal something important about the cultural presumptions and conventions that often slip into our academic research and scholarship.

The reason so many of Catholic moral theologians feel unsatisfied with their standard response to student questions about disability owes to the way we tend to conceive the topic of disability. Specifically, for many Catholic moral theologians, our approach to disability is often framed in advance by cultural judgments and theoretical presumptions that are tough to reconcile with the traditional Christian account of our common vulnerability to impairment, illness, and injury.

I want to highlight three salient features of contemporary theological engagement with disability that Catholic moral theologians ought to keep in mind. These three features, you’ll find, correspond to the three sections around which we’ve organized the Engaging Disability special issue from the Journal of Moral Theology.

First, there is common tendency within contemporary Catholic moral theology to uncritically frame the theological significance of impairment, illness, and injury according to what is called the “inclusion model” or the “social model” of disability. Specifically, when the topic is disability within society, in contrast to the legislatively enforced norms, protections, and ethos of liberal society (with its prioritization of individualism, autonomy, and the assertion of rights), the doctrinal and moral outlook framed by Catholic Social Teaching places the inalienable creaturely dignity and integral flourishing of persons at the center of theological consideration of the common good. In the first part of the Engaging Disability special issue, we have three examples of how the Catholic understanding of human sociality can inform the work of Catholic moral theology. Mary Jo Iozzio writes on the limits of civil accommodations and the extravagance of Christian mercy (God Bends Over Backwards to Accommodate Humankind…While the Civil Rights Acts and the Americans with Disabilities Act Require [Only] Minimum Effort); Mary M. Doyle Roach writes on self-disclosure and radical solidarity within the Christian community (From Universal Precautions to Universal Design: Disclosure of Concealable Disability in the Case of HIV); and Matthew Gaudet writes on large-scale societal shifts and the potential of Catholic Social Teaching (On “And Vulnerable”: Catholic Social Thought and the Social Challenges of Cognitive Disability).

Second, there is a tendency in contemporary Catholic moral theology to presume that inquiry into the moral implications of impairment, illness, and injury are new to the Christian theological tradition. This is a presumption that needs to be challenged, especially when thinking about how our bodily vulnerabilities and dependencies relate to the ordinary practices of Christian discipleship. To do that, we need moral theologians who have an aptitude for serious engagement with the dogmatic, systematic, historical, and canonical resources of Christian tradition—and who can explore those resources with an eye toward contemporary theoretical concerns. In the second part of the Engaging Disability special issue, we have three examples the difference disciplined engagement with the Christian tradition can made for the way we think about Christian discipleship and our common vulnerability to impairment, illness, and injury. Julia A. Fleming writes a historically disciplined essay on moral casuistry and the sacrament of penance (Seventeenth-Century Casuistry Regarding Persons with Disabilities: Antonino Diana’s Tract “On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind”); Jana Bennett writes a theoretically nimble reflection on contemplative prayer and the experience of people who are deaf (Blessed Silence: Explorations in Christian Contemplation and Hearing Loss); and Paul Gondreau writes a theologically rich personal essay on the integrity of our bodies and the object of our resurrection hope (Disability, the Healing of Infirmity, and the Theological Virtue of Hope: A Thomistic Approach).

Third, there is a tendency in contemporary Catholic moral theology to uncritically presume problematic and incomplete anthropological caricatures. Specifically, for the discipline of moral theology in the Catholic tradition, the distinctively Christian account of our innate vulnerabilities and coordinate dependencies (both corporeal and spiritual) define fundamental anthropological principles for Catholic moral theologians. Unfortunately, important aspects of the Christian view, relevant to our understanding of impairment, illness, and injury tend to be obscured. Clarity on those anthropological principles is essential if Christian moralists and ethicists are to recognize and avoid the dehumanizing implications that follow when we grant uncritical assent to the typical rationalistic and ideologically-truncated anthropological norms of modernity. In the third part of the Engaging Disability special issue, we have three examples of how traditional Christian theological anthropology can help Catholic moral theologians describe human happiness and the integral good proper to the human being. Lorraine Cuddeback writes on truthfulness, difference, and theological appeals to friendship (Becoming Friends: Ethics in Friendship and in Doing Theology); Jason Reimer Greig writes on the modern conception of time, and how Christian disciplines related to time shape our understanding of human flourishing (The Slow Journey Towards Beatitude: Disability in L’Arche, and Staying Human in High-Speed Society); and my own contribution to the collection treats the place of vulnerability in Christian anthropology, and why that should matter for Catholic moral theologians (The Goodness and Beauty of Our Fragile Flesh: Moral Theologians and Our Engagement With ‘Disability’).