Psalm 30: 2, 4, 5-6, 11, 12, 13

There is a comforting note of compassion in the readings for the Thirteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time in this cycle. This strikes me as the common theme across the three readings, but it is worth noting that each one has a particular nuance to the idea of Christian compassion that can help us see the moral significance of this perennial call.

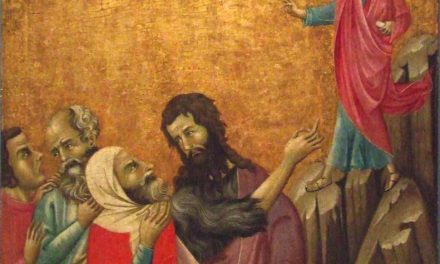

The importance of compassion is most apparent in Jesus’ interactions with Jairus and the “woman afflicted with hemorrhages” in the Gospel. Jesus is quick to head off with Jairus after he makes his initial plea for assistance with his daughter who is “at the point of death.” On the way, Jesus has a peculiar encounter with a woman who is also seeking healing. She reaches out to touch his cloak on the assumption that this slight connection will be enough to heal her because Jesus is that powerful.

As it turns out, she is right. She is healed, but Jesus immediately realizes that he has been touched and a healing has occurred. He therefore looks for the person whom he has healed, causing much consternation among the disciples (and, we can assume, among the crowd pressed around him). Afraid of an accusation, the woman “approached in fear and trembling,” but Jesus is not looking to punish her. He offers a compassionate response: “Your faith has saved you. Go in peace and be cured of your affliction.”

Meanwhile, we hear word that Jairus’s daughter has died. As a parent, I can only begin to imagine the devastation that this news would have occasioned for Jairus, but Jesus reassures him to “just have faith.” He then heads into Jairus’s home where he raises the little girl and restores Jairus’s family in a powerful, and truly compassionate act.

In both cases, we have the sense that Jesus intimately understands the agony of the petitioners before him. He comforts the woman who is terrified that she will be in trouble for touching him without permission and preserves the healing she needed. He responds immediately to Jairus’s request for help, and then helps him navigate the setback of bad news from home before finally giving him exactly what he desired—a healthy daughter once again.

God, this reading is telling us, knows what it is to suffer and therefore walks with us in a dramatic act of compassion to bring about the holistic healing we need. That is, God is not just healing our physical afflictions but also our emotional and psychological uneasiness in order to ensure our spiritual wellbeing. (On this last point, it is significant that Jesus tells the woman her faith has saved her and exhorts Jairus to have faith before his daughter is finally healed.)

The second reading, from St. Paul’s Second Letter to the Corinthians, highlights both why Jesus would behave this way and what we are supposed to do as a result of having witnessed this compassion. Thus, St. Paul highlights “the gracious act of our Lord Jesus Christ…[who] though he was rich, for your sake he became poor.” In this way he explains that the Incarnation is both the basis and the model of God’s compassion. It is the basis because it made the infinite God finite, such that Jesus experienced all the suffering that accompanies our limited human existence, including death. If compassion is literally suffering with, God has done this to the fullest by virtue of becoming flesh and dwelling among us. Jesus did not have to imagine the pain of the woman or of Jairus in order to be stirred to respond with compassion; in a very real way, he knew it, because he was human too.

At the same time, this profound act of God calls us to act as well. St. Paul uses Jesus’s example to invite his audience to be generous with their resources so that they might provide compassionate succor to others who suffer too. By giving money to help meet the needs of others, St. Paul insists, the Corinthian community (and, by extension, we too) can embody the same compassion of Christ.

At the same time, we must expect that there will be a limit to what our compassion can achieve. The first reading from the Book of Wisdom, shows that even God’s compassion does not eliminate all suffering. Happily, Wisdom reminds us that “God did not make death” nor will suffering to be a fact of life—this can be linked back to human sinfulness. (For more on the complex theological claims involved in this point, see Brian Davies’s thoroughly Thomistic The Reality of God and the Problem of Evil.) Yet, suffering and even death are a fact of human life now.

On one level, this would seem to call into question God’s compassion. Surely an all-powerful God can fix this problem. Obviously, God does have power over death (see: Resurrection of Jesus), but God does not exert that power in a way that removes death from our world. Quite honestly, I do not know why, but I do know that God is still compassionate in the face of this suffering—this is the clear message of the Gospel—and that we are called to be compassionate in the face of this suffering too—that is the clear message of the second reading.

Putting these pieces together, I see that the Christian call to compassion is not simply a call to fix everyone else’s problems. It is, instead, a call to a more genuine form of suffering with. When possible, we suffer with others in a way that removes their suffering, but that is never the point. The point is the growth of solidarity that emerges when we take another’s pain seriously enough to sit with them and understand it.

Samuel Wells, the Anglican priest and moral theologian, has a phenomenal explanation of this calling in a sermon on “Rethinking Service.” In it, he argues that there is a difference between doing things for other people and doing things with other people. The former is driven by a desire to overcome mortality, but the latter is motivated by a compassion that hopes to respond first and foremost to isolation.

The first is often desired more immediately, but it is bound to fail eventually. We cannot overcome death. This does not mean we cannot be compassionate, however. That is where responding with people becomes important. We may not be able to combat mortality in each case (everyone is going to die at some point), but we can always do something about isolation. We can always reach out in solidarity to be there with other people when they need accompaniment.

This, ultimately, is the message of compassion found in today’s readings. Yes, Jesus models a form of compassion that solves mortal problems. He does something for Jairus and for the woman with the hemorrhage. When we see suffering, then, we too must look for ways that we can help and help if we can (as the Corinthians certainly were in a position to do.) Even more importantly and more fundamentally, though, Jesus’s actions were motivated by the fact that he was ready to stand with Jairus, with the woman in need of healing, and with all of us.

Hence, a clear message emerges: when we can do things for others, we should; but even if we can, and certainly when we cannot, we are always called to be there with them. This is no less an act of compassion. In fact, it is the very act of compassion God show us, as “Emmanuel.”

Trackbacks/Pingbacks