Lectionary: 64

Isaiah 49:3, 5-6

Psalm 40

I Corinthians 1:1-3

John 1:29-34

Integral to the Bible’s portrayal of God is that he plans. “I know the plans I have for you,” declares the God of Israel, speaking through the prophet Jeremiah, “plans for your welfare and not for harm, to give you a future with hope” (Jer 29:11).

From even the most cursory understanding of God drawn from Scripture, one cannot help but notice that God does nothing on a mere whim. Everything he does and says—every interaction and intervention—is measured and ordained to some ultimate purpose. Unlike the cosmogonies of nearby cultures, the Israelite creation story depicts God’s activity as completely unprovoked and undisturbed, entirely uninfluenced by any forces or contingencies beyond his control. For unlike us, there is no gap between God’s intentions and his capacity to carry them through. As Isaiah once put it:

“As the rain and the snow come down from heaven,

and do not return there until they have watered the earth,

making it bring forth and sprout,

giving seed to the sower and bread to the eater,

so shall my word be that goes out from my mouth;

it shall not return to me empty,

but it shall accomplish that which I purpose,

and succeed in the thing for which I sent it” (Is 55:10-11).

Indeed, Scripture appeals to God’s all-comprehending and invincible purposes as a warrant for his credibility and authority. “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?” God asks Job, “Do you know the ordinances of the heavens? Can you establish their rule on the earth (Job 38:4,33)? Beautifully echoing this sentiment, Isaiah writes:

“Who has measured the waters in the hollow of his hand

and marked off the heavens with a span,

enclosed the dust of the earth in a measure,

and weighed the mountains in scales

and the hills in a balance? Who has directed the spirit of the Lord,

or as his counselor has instructed him?

Whom did he consult for his enlightenment,

and who taught him the path of justice?

Who taught him knowledge,

and showed him the way of understanding?

Even the nations are like a drop from a bucket,

and are accounted as dust on the scales.” (Is 40:12-15).

Even Jesus appeals to the unassailable sovereignty of God when he exhorts his followers to greater trust that God will provide for them:

“Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they neither toil nor spin, yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not clothed like one of these. But if God so clothes the grass of the field, which is alive today and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will he not much more clothe you—you of little faith” (Mt 6:28-30)?

You get the idea. God never does anything by mistake. He is in control. He has a plan; indeed, he has always (and forever) had a plan. And his plan is one ordered toward our redemption and salvation.

That being said, however, we would do well to reflect upon the particular quality of God’s actions in our midst, at least as they so often appear from our perspective. For while an unshakable assurance in God’s providence can and should arise from a clear understanding of divine perfection, such an assurance, distorted by pride, can also lead us into a fatal error: presumption. The perennial temptation for those who worship and follow a perfectly sovereign God is to associate his activity in the world with what we presume an agent with absolute control would do or say. In other words, we project our own practical rationality onto God’s, and so identify the vestiges of his work through the lens of how we might conduct matters if we had that sort of knowledge and power. Hence the common and entirely understandable dismay at the enormous amount of vulnerability and tragedy which God tolerates within his creation. If we were all-loving and all-powerful, surely we would not run things this way.

Of course the reason such presumption is fatal is that is a form of idolatry, to which God repeatedly responds in Scripture with the question, “What would have me do? Do you think I am like your self? Would you really want me to act as you do?” (cf. Ps 50). “My thoughts are not your thoughts,” the Lord declares in Isaiah, “neither are your ways my ways” (Is 55:8).

While God may have perfect knowledge of his eternal intentions and perfect power to accomplish them, the actual implementation of his purposes in history are anything but predictable. They are anything but the absolute sublimation of our own perennial attempts to determine the progress of society or make provision for the future well-being of creation. Again and again, God’s most significant acts throughout the course of his relationship to the world appear out of nowhere, utterly unpredictable and way outside the boundaries within which we were expecting them. So it is with God’s call of Abraham; so it is with God’s election of Moses and David; and so it is with the wondrous advent of God’s incarnation through a poor peasant girl from Nazareth.

But it wasn’t only Mary’s call that was surprising and unpredictable. Above all, it was the work of John the Baptist, the forerunner without whose prophetic ministry the mind-blowing identity of Jesus might never have found a foothold. For Christians, everything of pertinence to God’s interactions with us can be centered upon and derived from the person of Jesus Christ, since He is the very Word of the Father made flesh. In Jesus we have before us a concrete manifestation of all the eternal purposes of God. “For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross” (Col 1:19-20). Yet how could such a conception even receive the slightest consideration within the historical community set apart from its neighbors precisely on account of its abiding belief that God is not part of the creation he brought about?

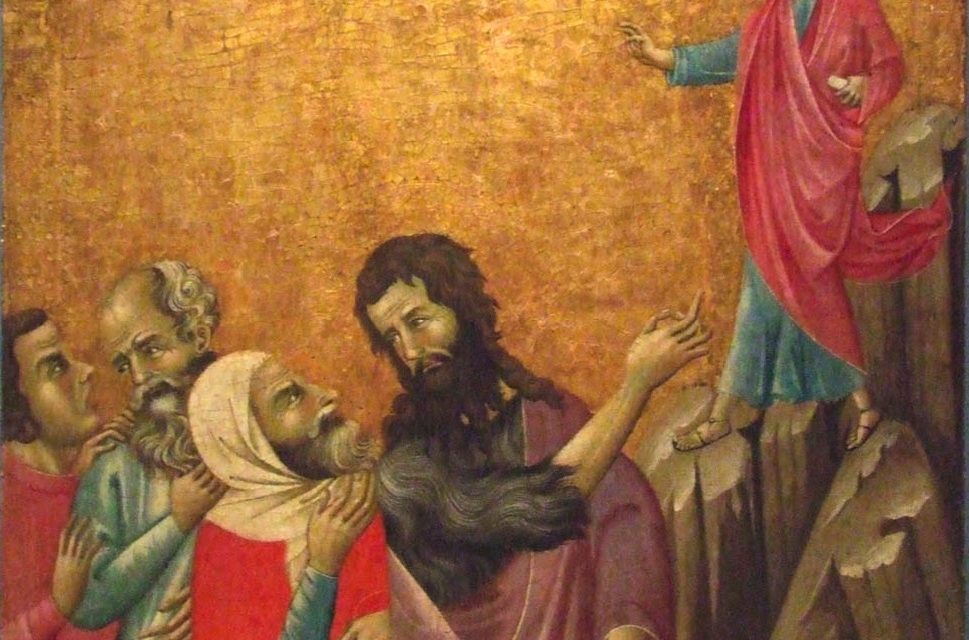

God’s plan to redeem the human race requires intellectual vehicles for its mediation just as much as material ones. It would have been unintelligible if any average first-century Jewish authority would have proposed without prelude that Jesus of Nazareth, son of Joseph the Carpenter, is the “Word made flesh,” the “Son of God,” or even the “Lamb of God.” Yet when placed in the mouth of John the Baptist, such claims not only take on sufficient weight to demand some degree of consideration, but they are able to set in motion a process of thought that culminates in the seminal apprehension of the truth lying behind them. He is the one who first sees Jesus this way, as the “Lamb of God.” He is the first recipient of a sign that marks Jesus as “the One who is to come,” who will baptize not with water but with the Holy Spirit. John the Baptist glimpses the preeminence of Jesus, and is able to declare it in a way that will grow into a testimony that can be passed on for the sake of the world’s salvation.

These theological notions about John the Baptist seem fairly straightforward now, but in John’s own day they could have held little to no meaning at all. The categories were still latent, and so the message still inchoate. How could anyone have understood what John was really talking about when he calls Jesus “the one who is to come” and the “Son of God.” Integral to the initial credibility of these claims, and hence to God’s plan of conveying the truth about Jesus’ identity, is the established character of John the Baptist. John was extraordinarily eccentric and extreme (even by ancient standards), but he was also seen to hold great power. Unlike today, when we would most likely label one who behaved as John did “mentally ill” and so feel justified in subjecting him to non-voluntary psychiatric treatment, the people of John’s day took him seriously. His otherness, his wildness, was regarded as a sign of a privileged perspective on the intentions of the One whose thoughts and ways are so different from our own. Like the prophets before him, he was “set apart,” and heedless of the boundaries and obligations of the status quo, whether social or cultic.

Even the established authorities of the day took him seriously. Indeed, the testimony we hear in this Sunday’s gospel is given in reply to the questions posed by the “priests and Levites” sent to him by the Jewish leaders in Jerusalem. What they must have made of what he said I cannot possibly imagine, but there must have been a good deal of puzzlement. John’s avowals that Jesus “existed before him” and that he “did not know” Jesus, when placed within the context of the gospel narratives already in existence by the time St. John penned this passage —narratives such as Luke’s, which identify John the Baptist as being a slightly older relative of Jesus’—clearly point to the Baptist’s apprehension of an identity that transcended Jesus’ familial and social history. Just as the authorities and the whole of the Israel (excepting perhaps Mary and Joseph) did not know who Jesus of Nazareth really was, so John himself confesses that he did not really know until he saw the Spirit descend upon him like a dove.

John was apparently prepared for this moment. One might even say that his whole life and his whole ministry was a prelude to this moment, when he was finally able to say “there he is: he is the one about whom I have been speaking. He is the one whom we have been waiting for, the one who will baptize us with the Holy Spirit and burn our sins away. So much hinges on that moment! Perhaps that is why, after the first few lofty sentences of John’s prologue (in the beginning was the Word, etc.), St. John begins the historical narrative of his gospel with an introduction of John the Baptist: “There was a man sent from God whose name was John” (Jn 1:6). It is through the life and work of John the Baptist, the “Forerunner” of our Lord, that we are now able to confess (even if incompletely) the true identity of our Lord, God, and Savior Jesus Christ. Without him, the Word made may still have come, but we may not have received that Word with sufficient attention or consideration. There were others of course who proclaimed the truth of Jesus’ identity, such as the Magi or Simeon & Anna, but it was John the Baptist who without doubt played the pivotal role in the conceptual mediation of God’s self-revelation to Israel through the person of Jesus Christ.

And so we Christians now joyfully proclaim that God has come among us in the fullness of His glory, and we have received the grace and truth mediated to us through His Word. Yet at the same time we must bear in mind that this glory still works among us in wildly unpredictable ways. The incarnation has not tamed the wildness of God’s interventions in human history; his thoughts and ways are just as “other” now as they were in the time of Isaiah. And so it bears asking: how might we perceive today, in the light of the incarnation, the unforeseen and uncontrollable purposes of God at work in the world? Who are the prophets in our midst? What are they saying, and how might they be revealing God’s invincible intentions unfolding in our own time and place? Whatever answer we discern to these questions, two things are certain: first, if we wish to apprehend God’s glory when it appears in our midst, we must, like John, remain in continual contact and dialogue with the Lord; and second, this divine glory will almost certainly look nothing like we or the world expected. God’s perfect wildness is still at work among us, visible only to prayerful hearts radically open to the unfamiliar and unexpected. Let us pray that the Lord will transform our own hearts accordingly, so that we may behold his purposes aright.