Genesis 15:5-12, 17-18

Psalm 27

Philippians 3:-4:1

Luke 9:28b-36

… contemplation is very far from being just one kind of thing that Christians do: it is the key to prayer, liturgy, art and ethics, the key to the essence of a renewed humanity that is capable of seeing the world and other subjects in the world with freedom – freedom from self-oriented, acquisitive habits and the distorted understanding that comes from them.

– (Retired) Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams’ address to the Synod of Bishops on the New Evangelization (10/10/2012)

Recently I have been doing some research into the connections between spiritual and moral formation, and in my last lectionary post I discussed the four senses of Scripture (literal, moral, allegorical, and anagogical), the last of which – the anagogical or mystical – involves contemplative resting in God’s presence via the Word. So it is entirely possible that I am overly eager to highlight the mystical elements of Scripture. However, the readings for this second Sunday of Lent seem saturated with mystical experiences.

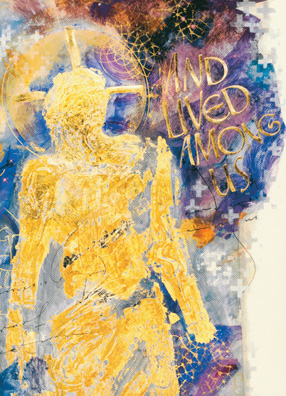

For example, after making a sacrifice to God, Abram falls into a trance, “and a deep, terrifying darkness enveloped him,” and the scene ends with God making a covenant with Abram, promising the land to his descendents. In a similar fashion, Peter, James, and John witness Jesus’s transfiguration as “his face changed in appearance and his clothing became dazzling white” (see the beautiful image from the St. John’s Bible to the right – worthy of lectio in its own right). After seeing Jesus conversing with Moses and Elijah, “a cloud came over them and cast a shadow over them, and they became frightened when they entered the cloud.” While lectio divina and meditation with these texts is always rewarding, I have found these stories to be particularly fruitful in their description of these mystical encounters with God.

In regard to morality, the reading from Paul bears most closely on the connection between morality and contemplative spirituality. He begins by exhorting his listeners to be imitators of him and of others who conduct themselves in a manner worthy of the Gospel. But then the letter builds to his statement that “[Christ] will change our lowly body to conform to his glorified body by the power that enables him also to bring all things into subjection to himself.” Paul moves from a moral foundation to the ultimate source of Christian life, the power of the Holy Spirit that transforms the human person more fully into the divine image.

While discussing the connection between the active (i.e., moral) and the contemplative life, Thomas Aquinas uses a Latin word dispositive to describe the way in which moral practices lead into contemplation (ST II-II. Q.180, A.2). The Latin adverb dispositive translates to “dispositively,” as in “to be disposed toward” a particular kind of activity. (I had to look up both the Latin and the English definition of these terms!). In other words, the human effort involved in moral practices disposes one to be more receptive to God’s grace and to contemplative practices such as resting peacefully in God’s presence – fulfilling the Psalmists desire, “Your presence, O Lord, I seek.”

This pattern of moral asceticism that enables one to be disposed to deeper levels of contemplation of the mystery of Christ is quite fitting for a Lenten reflection upon the Scriptures. I have found it helpful in my Lenten practice in recent years to engage in a combination of asceticism (giving up something good) and embracing some kind of positive practice (like extra time for lectio, etc.) to intensify my focus during the period of Lent. Thus, following the pattern of these readings, I would like to suggest that we can see our Lenten practices as a form of moral asceticism that is not intended to be some morbid self-denial, but rather as a way to dispose ourselves to enter more deeply into the mystery of Christ’s suffering, death, and resurrection.

In fact, I would argue that it is only in light of such larger contemplative goals that self-denial and asceticism make any sense. Without the purpose of directing our energies to some higher purpose – resting in God, contemplating the mystery of Christ and our salvation – these practices become tedious, externally imposed, and they tend to foster an unhealthy – and unbiblical – rejection of the body and the physical world as the source of evil. In other words, they lack the capacity to lead us into deeper spiritual maturity and wisdom. Of course, this process only works when it is done willingly, and with God’s help. Forcing or guilting Christians into such practices only further alienates them from the beauty of the contemplative tradition of Christianity, but inviting people lovingly into the beauty, joy, and challenge of growing closer to Christ is the best means of evangelization and witness in the modern world (or so I would suggest).

How might these readings call you into a gentle practice of moral asceticism (no self-mortification please) that might help you to be more disposed to hearing and responding to the promptings of God’s grace this Lent? Often, it is the small gestures that adjust our presence of mind and bring about the most surprising results.