As a white person of privilege, and along with several of my white colleagues who focus their academic work on racial justice, I’ve found myself profoundly convicted by this discourse. Indeed, the racial justice lens—from the Bronx/Manhattan (where I work) to “the Oranges” in the NJ (where I live)—has helped me see profound injustice where I couldn’t see it before. And though discussion of this topic is seemingly everywhere these days (even in a recent Fox News exchange in which Megyn Kelly tried to convince Bill O’Reilly that white privilege is a thing) I’m a relative newcomer to the discourse and obviously still have much to learn.

Though my primary reason for writing this post is to make a brief and preliminary attempt to draw attention to subaltern voices of color on the topics of euthanasia and abortion, I also hope those of you who are doing more intense theological (and other) work on racial justice offer your expertise and comments.

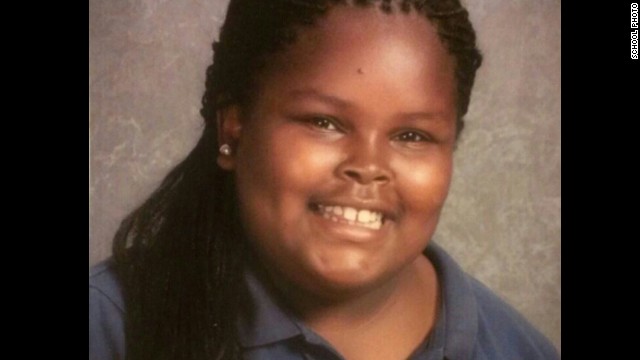

Remember the story of thirteen year-old Jahi McMath? She was declared dead by multiple neurologists and the state of California back in December. She even has a death certificate.

But her mother has firmly rejected these determinations. Indeed, here is a story on an address she recently gave at a gala for New Beginnings Community Center:

“Some days I ask her to move her left hand, or her right hand and she does…I’m her mom and I know that my daughter is in there,” Winkfield said through tears.

Winkfield credited Scerri and New Beginnings, which said they’d provide 24/7 care for Jahi, for helping convince a California judge to sign an order authorizing the child’s release from the hospital.She was removed by the coroner’s office.

The ballroom last night was filled with similar stories — messages of hope, faith and perseverance: “Never, ever give up,” in Winkfield’s words.

Is it possible that Jahi is still alive after being declared brain dead? Wouldn’t be the first time. Furthermore, there is increasing—not decreasing—debate about whether brain death is actual death. Brain “dead” individuals can fight off infections, react to bodily trauma, and even gestate children. In short, they have the homeostasis of living human organisms.

And the more we learn about consciousness the more we unlearn what we thought we used to know. We used to think, for instance, that those in (the terribly named) persistent vegetative state were not conscious—but now we know that at least some of them are. My reading of the most recent literature is that consciousness is almost certainly not something that we should think of as being “housed” in the brain. Interestingly, more and more people are arguing that consciousness is a function of the organism, holistically considered. Jahi’s mother had good bioethical reasons to be skeptical of what she was told about her daughter.

She also had good historical reasons.

The Root’s Janell Ross has a fantastic piece on Jahi’s case which puts it in the context of a long and disturbing history littered with reasons why many African Americans mistrust the power structures which create and determine our end-of-life practices. Consider the numbers she cites:

A November Pew Research Center poll found substantial differences in the amount, timing and type of medical intervention that black and white Americans believe to be appropriate. In fact, only 33 percent of blacks said that there are circumstances in which patients should be allowed to die, compared with 65 percent of non-Hispanic white Americans. Another 61 percent of blacks told Pew researchers that doctors should be obligated to continue and provide any type of care possible, while just 26 percent of whites agreed.

Ross also cites a study by the Institute of Medicine which found that African-American patients were “less likely to receive lifesaving cardiac bypass treatment, dialysis and other treatments than white patients with the same health challenges, insurance status, income and age.” Her story even notes that hospital officials publicly referred to Jahi as a “dead body” and insisted that treating her would be unethical.

It is also worth mentioning, as I recently argued in a piece for ABC Religion and Ethics, that current movements in support of legalized euthanasia center rest on (1) the assumption of autonomy and (2) consumerist standards for determining whether a life is burdensome or beneficial. Almost always invoked by white people of privilege, these two concepts are rightly critiqued by several of my friends and colleagues who raise up marginal voices in the name of racial justice.

The other major set of (traditional) life issues, of course, surrounds the issue of abortion.

In my forthcoming book I show that the demographic shifts in this country, particularly when it comes to race, are in the process of fundamentally changing the American abortion discourse. Dr. Victoria M. DeFrancesco Soto of NBC Latino, for instance, recently noted that Latinos are significantly more skeptical of abortion than are non-Latinos.

But beyond shifting public opinion, consider the issues of structural injustice. According to Guttmacher, African American women get 30% of all abortions despite being only 13% of the population. Hispanic women get 25% of all abortions despite being 16% of the population. Virtually no one argues that there is a systematic attempt to intentionally target peoples of color for abortion, but the sin present here is structurally similar to the sin present those social structures which negatively impact, say, education and ecological health in poor communities of color. Especially if a diverse plurality of us can agree that abortion is a bad thing and should be “rare”, shouldn’t this kind of structural injustice be called out in similar ways?

Despite what has been presented in this post, at least when it comes to euthanasia and abortion, I must say that I haven’t seen the skeptical, subaltern voices of color lifted up by academic racial justice discourse. And especially given how these two sets of issues impact politics and the Church in the United States, this at least appears to be a major-league missed opportunity.

It is more than possible (and perhaps even likely) that as a newcomer to this discourse I may have not yet come across voices from the academic discourse on racial justice (especially, but not only, from theology) who are lifting up the voices of color who are skeptical of euthanasia and/or abortion. If they have the interest and inclination, I’d genuinely appreciate learning more from the critiques, amendments and suggestions of colleagues who are more familiar with the discourse.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks