You could teach a whole semester-long class on moral theology through the lens of Les Miserables, Victor Hugo’s epic examination of “the miserable”–the downtrodden and forgotten part of society. The novel turned musical turned recent film starring Hugh Jackman, Russell Crowe, Anne Hathaway, and a whole host of other stars is a marvelous study in social justice, beginning with Jean Valjean in prison serving an unjust sentence for a crime committed more against him than by him and ending with the idealistic students dying at the barricade as martyrs for a better world during the French Revolution. But the story’s characters also highlights certain key approaches to ethics, effectively carving out a typology of ethical theories.

First, there are the egoists, represented by the Thenardier couple. They have no values outside of self-interest; they have no God besides profit:

But we’re the ones who take it

We’re the ones who make it in the end!

Watch the buggers dance

Watch ’em till they drop

Keep your wits about you

And you stand on top!

Masters of the land

Always get our share

Clear away the barricades

And we’re still there!

We know where the wind is blowing

Money is the stuff we smell.

And when we’re rich as Croesus

Jesus! Won’t we see you all in hell!

Then there is Javert, the chief of police who chases Valjean through Paris and through the years after Valjean breaks his parole to become a new man. Javert is a deontologist, committed to rules and duties. For him, the good and the true is found in the law, not only the law of France but also the law of God reflected in the order of the universe. His soliloquy is probably my favorite:

Stars

In your multitudes

Scarce to be counted

Filling the darkness

With order and light

You are the sentinels

Silent and sure

Keeping watch in the night

Keeping watch in the nightYou know your place in the sky

You hold your course and your aim

And each in your season

Returns and returns

And is always the same

And if you fall as Lucifer fell

You fall in flame!

And perhaps the best line in the play and in the film is during Javert and Valjean’s final confrontation, when Valjean tells him that he doesn’t hold a grudge, that he isn’t filled with hate towards the man who has haunted him for decades. He tells Javert, “You’ve done your duty, nothing more.” There are two ways we can take this. Valjean could be excusing Javert for his misdeeds since he was only acting out of duty. This was the excuse made by the “good Nazis” at Nuremberg and the excuse still made by people like Lynndie England today. But Valjean could also be accusing Javert with these words. “You’ve done your duty, nothing more” is precisely what is wrong with Javert.

See, Javert isn’t a bad guy, really. We misunderstand him if we make him a demon. True, he doesn’t know mercy, but that is only because he is so committed to the moral law. His story reveals the shortcoming of deontological theories–the law alone is not enough to make a person righteous or good. The law is a pedagogue. It points us to the end, but it isn’t an end in itself. In conflating the law with God, Javert misses who God really is–Love.

Then there are the various consequentialists. The best song illustrating consequentialism is the factory ladies singing “At the End of the Day” as they urge the foreman to turn Fantine out on the street:

At the end of the day

She’ll be nothing but trouble

And there’s trouble for all

When there’s trouble for one!

While we’re earning our daily bread

She’s the one with her hands in the butter

You must send the slut away

Or we’re all gonna end in the gutter

And it’s us who’ll have to pay

At the end of the day!

The ends justify the means for these women. And they show us too the fatal flaw of consequentialism–it allows the minority (Fantine) to be sacrificed for the sake of the majority. Valjean toys with consequentialism but ultimately rejects it when the man mistaken for him is brought to trial:

I am the master of hundreds of workers.

They all look to me.

How can I abandon them?

How would they live

If I am not free?If I speak, I am condemned.

If I stay silent, I am damned!

Which brings us to Valjean. He is a study in virtue ethics. “Who am I?” is the question that guides his moral choices. His powerful soliloquy by this title continues,

Can I condemn this man to slavery

Pretend I do not feel his agony

This innocent who bears my face

Who goes to judgement in my place

Who am I?

Can I conceal myself for evermore?

Pretend I’m not the man I was before?

And must my name until I die

Be no more than an alibi?

Must I lie?

How can I ever face my fellow men?

How can I ever face myself again?

My soul belongs to God, I know

I made that bargain long ago

He gave me hope when hope was gone

He gave me strength to journey onWho am I? Who am I?

I am Jean Valjean!

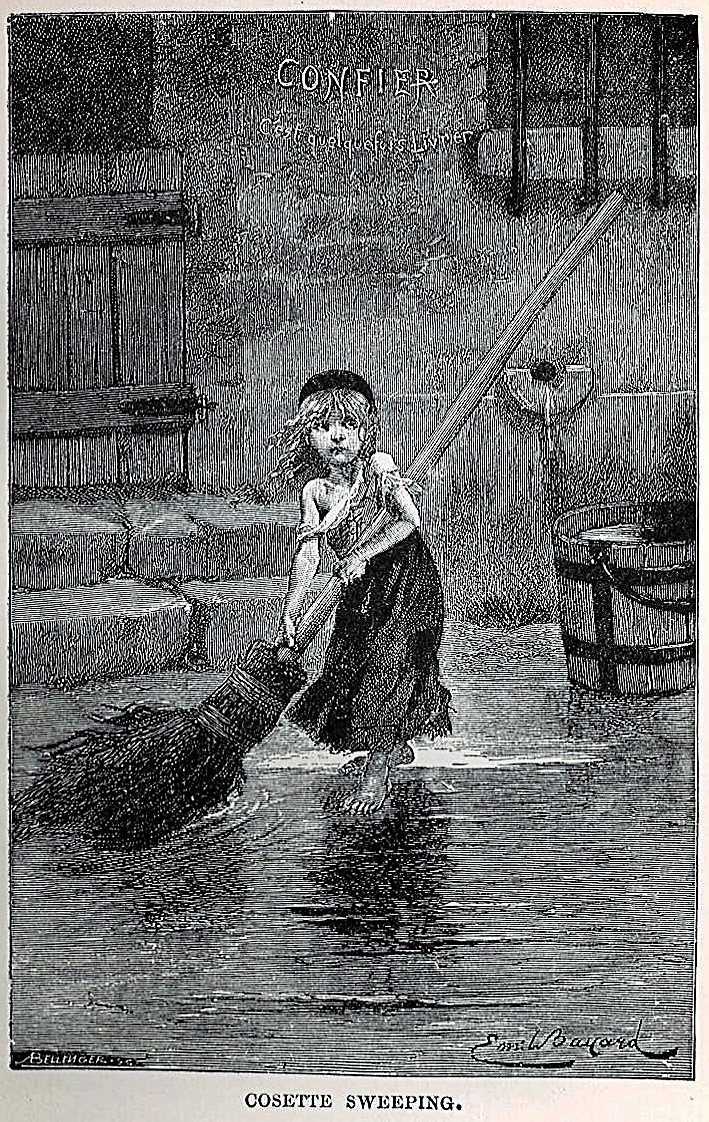

What is fascinating about Valjean is how he must continue to re-ask himself the question “Who am I?” and how the answer continuously leads him to make different choices. After his confrontation with the bishop who shows mercy on Valjean and gives him the means to become a righteous man, the question leads Valjean to break his parole, to take on a new identity, and to literally become a new man. He breaks the law here (which is why Javert pursues him) but who could blame Valjean? He might have broken the law of France but almost anybody would agree that he does the moral thing here. And when he reveals his true identity to the courts, he fights Javert and again runs from the law to go and save Cosette. Again, he breaks the law of France but Valjean is definitely still on the side of the moral law. And finally, when he finds out that his Cosette is in love with Marius, the question “Who am I” leads him to the barricades and then to the sewers to save Marius’ life. It isn’t that Valjean is above the moral law; it is just that he recognizes that the moral law does not always conform to the external law. One hears echoes of Jesus: “The sabbath was made for man, not man for the sabbath.”

In the end, Valjean is a man, “no worse than any other man,” as he explains to Javert. The critical difference between the two is that Valjean is willing to live out a life of mercy. He is willing to both give and receive it while Javert can do neither. When Valjean offers Javert mercy, saving his life at the barricade, Javert is tormented. His system is broken, his god dead. As his world comes crashing down, he plunges into the Seine. Valjean, on the other hand, looking up with shame into the eyes of the bishop whom he just stole from, chooses to accept mercy, and then give it in return–to Fantine, to Cosette, to Marius, and even to his enemy.

Victor Hugo apparently had a strained relationship to the faith but the story has a very Christian message: “To love another person is to see the face of God.” As human beings, we are made for mercy. It is in mercy that we live; it is in judgment that we die. Jesus tells his disciples in the gospel of John, “I have come that you might have life, and have it more abundantly.” Jesus comes in mercy to lead us to life because we are incapable of finding it on our own, as Javert shows us. Jesus in turn asks us to lead others to that life by loving our neighbor, by showing them mercy, by forgiving them as we wish to be forgiven. In living a life of love and mercy, whatever our circumstances, whatever our class, whatever our faults, we come to know God, and we come to see God in this world, this broken and fallen and oftentimes all-too-miserable world he came to redeem.

Beth, this is great. I thought about similar themes when I watched the movie a few days ago. I focused more just on the contrast between Javert and Jean Valjean, though, and what came to my mind was Kierkegaard’s Either/Or and Concluding Unscientific Postscript. In Either/Or, Kierkegaard contrasts two ways of life, the aesthetic and the ethical. He introduces the character of Judge Wilhelm, who represents the ethical life. The ethical life basically has Kantian, deontological tones; it is the life of duty according to universal and objective morality. In some of his other writings, Kierkegaard introduces the idea of a third stage, that of religious faith, and some of his best explanation of what this entails is found in the Concluding Unscientific Postscript. Here he introduces the idea of subjectivity, which doesn’t mean relativism, but rather that unlike certain truths about the world outside of me, there are other truths that make demands of me if I am going to accept them as true. Kierkegaard believes that it is a mistake to try to understand what it means to be human in terms of some universal essence of humanity; we understand ourselves through introspection on our own personal experience as a subject. The truth of Christianity is also the sort of truth that can only be known subjectively. For Kierkegaard, the three stages are not contrasts (despite the Either/Or title) but in a sense one stage transcends and encompasses the previous. So the stage of religious faith is not anti-ethical, but it does go beyond the demands of universal duty; this also leads to Kierkegaard’s theory of the “teleological suspension of the ethical” in Fear and Trembling, in relation to Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac.

So turning back to Les Miserables, I thought Javert very much fits the ethical stage of life. As you mentioned, he is very much focused on universal laws, and throughout the story he has a hard time understanding how the uniqueness of personal narratives can make things different from what they appear, such as the prostitute forced into her position through misfortune. Valjean, on the other hand, is the embodiment of subjectivity. As you mentioned, his most important song is “Who Am I?” It is a reflection on his own subjectivity, and obviously part of that is his personal response to God. He relates to God as a subject, while Javert relates to God as if the latter was a universal lawgiver.

Also I think Kierkegaard gives us a third and more satisfactory explanation of what Valjean means when he states that Javert is simply a good man doing his duty. Kierkegaard sees the ethical as the pinnacle of what human goodness can achieve. Anything more belongs to God. Kierkegaard ends Either/Or with the reflection that before God, we are all sinful. But this recognition is what opens the possibility for religious faith. I think that in this reading, Valjean can truly mean that Javert is good because he does his duty, and that he himself is no worse than any other man, despite his clear difference from Javert. We might also say that Javert commits suicide because he is beginning to come to the realization that despite his ideals, he is also a sinner, but that he fails to reach the conclusions of the stage of religious faith.

Great, Matt. I don’t know that Javert really grasps his sinfulness in that final scene. If we contrast this scene with Valjean’s conversion, Valjean stares into a world “full of his sin” whereas Javert stares into a world “that cannot hold.” His thoughts prior to committing suicide are not really about himself. They aren’t introspective. They are about Valjean: “Damned if I’ll live in the debt of a thief . . . I will spit his pity right back in his face. There is nothing on earth that we share. It is either Valjean or Javert.”

Another way I thought of making sense of Javert is in terms of Calvinist election. Javert, I think, sees himself throughout the story as one of the elect as indicated by his success. He was born poor, in a prison, to “scum” and yet he rises to the esteemed position that we see him in. Valjean, on the other hand, he sees as reprobate. Valjean stole, went to prison, and tried to escape unsuccessfully. The signs all point to him as not being one of the elect. This is why Javert insists that Valjean can never change in that great dialogue after Fantine’s death. The reprobate can’t become elect and vice versa. But then right before his suicide, when Javert sees his sinfulness, he doubts his election. And if he is already damned, why not commit suicide? He is going to hell either way: “Instead I live, but live in hell.”

I had the same thought about Kierkegaard after watching the film. I watched, bawled my eyes out, thought about how Kierkegaardian the themes seemed to be, and thought I’d Google it and found this site.

Although, I felt that Javier and Valjean represented two competing and mutually exclusive interpretations of God (compassionate Vs vengeful), rather than seeing it as the ethical Vs the religious. Although your interpretation I think also fits well, the story paints Javier as religious in his foundations, and his need to die at the end makes me feel it’s better viewed as two competing views of God, one of which has to be extinguished by the end of the story.

They’re both perfect in their ways… Valjean, after his conversion, is perfectly compassionate, and Javert is perfectly vengeful. He’s not at all immoral though: when he thinks he’s falsely accused Lemere of being Valjean, he reports himself and expects be punished. Later, when he sees Valjean has the opportunity, he expects (almost demands) Valjean to kill him. Valjean acknowledges this at the end, too. Javert is perfect by the standards he represents, I feel.

Valjean’s compassion has to kill Javert, I think, (Javert kills himself, but before doing so he says that Valjean, by saving his life, has also killed him) because that represents the triumph of the view of a compassionate God over that of a vengeful God. The two are mutually exclusive and only one can still exist at the story’s resolution.

Also, I cried the most during those scenes where it’s the theme of compassion Vs vengeance that was at play: when Valjean is reflecting on the actions of the Bishop; when Fantine is expressing her loss at the hands of the lack of compassion. The romantic scenes and the political scenes are really moving too–and this is where I think the aesthetic and ethical spheres are explored (the sub plots of the love between Marius and Cosette, and the Revolution)–but it’s the story of Christian compassion that absolutely tore me apart, fittingly reflecting the view that its that sphere that’s the highest. It’s one thing to say it in theory, but through that combination of story and music, it absolutely puts one right through the experience and seems to demonstrate this, rather than just arguing it.

I so love this story. I’ve never read the book… it’s now on my must read list.

Beth,

I agree that you could teach a whole class on this! But I think the most profound moment (not sure if it is the same in the film) is the incident which leads to Valjean’s conversion: the incredible act of grace by the bishop from whom Valjean has stolen silver plate. Instead of having him arrested, the priest makes a further gift of silver candlesticks to him and makes the thought-provoking statement that by this act, “I have bought your soul for God!” It is this very gratuitousness which transforms Valjean and he says,

“My life was a war that could never be won

They gave me a number and murdered Valjean

When they chained me and left me for dead

Just for stealing a mouthful of bread

Yet why did I allow that man

To touch my soul and teach me love?

He treated me like any other

He gave me his trust

He called me brother

My life he claims for God above

Can such things be?

For I had come to hate this world

This world which had always hated me

Take an eye for an eye!

Turn your heart into stone!

This is all I have lived for!

This is all I have known!

One word from him and I’d be back

Beneath the lash, upon the rack

Instead he offers me my freedom,

I feel my shame inside me like a knife

He told me that I have a soul,

How does he know?

What spirit came to move my life? Is there another way to go?”

I think it is this experience of such mercy and grace which then allows Valjean to become a man who shows mercy to others…

Laurie,

I agree! The bishop steals the show as far as I am concerned. What is cool about the film is that the bishop is played by the man who sang Valjean in the tenth anniversary Dream Cast edition, by far the best Valjean if you ask me. Interesting ethical issue–the bishop lies to the officers who bring Valjean back, silver in arms. He tells the officers that he gave Valjean the silver. Does he sin there? I think not, though on the face of it, he does lie. As Matt points out, I think we might have a teleological suspension of the ethical at work here.

The film I think does a good job of this scene of conversion, with Valjean (played surprisingly well by Hugh Jackman) pacing before a crucifix in the bishops’ residence, culminating in his decision to tear up his parole papers and throw them over the side of a cliff.

A few minor corrections and/observations:

* The battle portrayed in Les Mis is the 1832 June Uprising, which took place over forty years (and four regimes) after the French Revolution. After the Ancien Regime was overthrown in the Revolution, France was ruled by the First Republic, then Napolean, then the restoration of the Bourbons, and then the so-called July Monarchy; the 1832 June Uprising was a failed revolt against the July Monarchy. (French politics at the time was a bit more complicated then portrayed by Hugo, let alone then portrayed by the musical).

* In the musical, Javert is portrayed as a religious man, who believes that the law is the path of righteousness, and that he is doing the Lord’s work in his policing. In the novel, Javert is not overtly religious; his zeal for the law is organic as opposed to backed by faith.

Fantastic article – thanks very much. I’m taking my youth group to see the stage version of Les Mis in April (our Lenten programme will introduce them to it) and I’ll use this article to help guide the discussions.

Incidentally, not only is Colm Wilkinson (the Bishop in the film) the actor who sang the role in the Tenth Anniversary Dream Cast concert, he’s also the actor who created the role both in London and on Broadway.

According to Edward Behr’s “The Complete Book of Les Miserables,” the first time Wilkinson sang “Bring Him Home” in rehearsal there was complete silence in the theatre for about a minute.

“Look,” director Trevor Nunn said, “I told you all that this was a play about God and it would be a very spiritual experience for us.”

“I know it’s *about* God,” one of the actors said. “But you didn’t tell us you’d engaged Him to *sing* it.”

Plenty of religious traditions value mercy. Nothing distinctively Christian about that. Valjean shows no sign of faith in, or even interest in, anything other than the most generic “God” of a post-Enlightenment French intellectual.

Thank you for this post, thoroughly enjoyed reading it.

Having just seen the film I was struck by the profound theological resonances throughout, but particularly by the imagery. It seemed to me that Valjean is depicted as overtly Christlike. During the revolutionary battle for a new world free from oppression (much as the Israelites longed to be freed from oppression by the Romans) Vanjean plays no active role in the main battle but rather descends into the earth and then reemerges. In doing so he saves the young man. The young man descends with Valjean and is raised to new life through Valjean’s efforts in what seems to be a direct parallel of the death, descent and ressurection of Christ.

It is also seemed striking that the figure of the law (Javert) is put to death (so to speak) by the grace of Valjean. This seemed to represent the succession of grace from law, the transition from the old covenent to the new.

“He tells the officers that he gave Valjean the silver. Does he sin there? I think not, though on the face of it, he does lie. As Matt points out, I think we might have a teleological suspension of the ethical at work here.” (by Beth Haile)

I’m not happy with that sort of excuse for sin but I can’t find any one willing to stand up for what it was. The Bishop sinned.

A “teleological suspension of the ethical” is making an excuse to avoid the truth.