Voters in the US presidential election will have many issues to consider prayerfully as we move closer to November 3. CMT bloggers will be exploring a range of issues and reflections on political participation in our Conscience at the Polls Series. To see the introductory post, go here.

In 2020, the intrinsic evil of racism must be an issue for thoughtful, prayerful consideration by Catholic voters. As a white person I know that speaking truthfully about white supremacy and white privilege—in our country’s past and in our country’s present—is not easy for white people. It is not easy for me, personally, to speak about my experiences of white privilege and the advantages I experience as someone who is white. I wrestle with feelings of shame and guilt. But our fellow citizens and our bishops are calling us to lean into this difficult conversation. I know that I have felt tempted to get defensive or to push away “the race question” before. Ironically, having the social power to do that proves that white people have privilege that is often underacknowledged. In other words, I have so much power that I don’t even have to think about how much power I have, and at whose expense.

Still, there are reasons for pause. “Probably one of the most telling signs that we have problems talking about race in America is the fact that we can’t even agree on what the definition of racism actually is,” writes Ijeoma Oluo. Add to that the fact that it takes courage to admit one’s racism. I like to think of myself as a good person, doing my best to make the world better. Seeing myself as racist complicates that picture of myself. I’m a good Catholic! I go to Mass! I pray! I tithe! I send my kids to Catholic school! How could I be racist?

That’s why it is important to move beyond a definition of racism as a personal prejudice and to connect it to systems of power as well as the realities of unconscious bias. Here are some helpful definitions from a variety of authors:

Racism is:

- “a prejudice against someone based on race, when those prejudices are reinforced by systems of power.” (Ijeoma Oluo, “What is racism?” in So You Want to Talk about Race, 27).

- “an underlying color symbol system that (1) justifies race-based disparities; (2) shapes not only behavior, but also one’s identity and consciousness; and (3) often operates at a preconcious or nonrational level that escapes personal awareness.” (Bryan Massingale, “What is racism?” in Racial Justice and the Catholic Church, 42).

- “a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produces and normalizes racial inequities.” (Ibram X. Kendi, How To Be An Antiracist, chapter 1).

Examples of racism abound in 2020. It isn’t just the rise of white nationalism and alt-right hate groups, as troubling as those are. It is also new evidence of health disparities, including evidence that racial and ethnic minority groups are being disproportionately affected by COVID-19. We see racism in the school to prison pipeline, underfunded public education, and racialized differences in access to online learning in COVID-19. After the death of George Floyd and groundswell of protests around the country this summer, Business Insider put together this series of 26 infographics that demonstrate the stark differences between Black and white experiences in the US because of systemic racism. For example:

- The poverty rate for Black families is over twice that for white families.

- The share of Black households who own their own homes is lower than other racial groups.

- Black men are roughly five times more likely to be imprisoned than their white counterparts.

It is clear that we live in a racist society in which racial groups do not have equal access to goods for human flourishing. Anyone living in this society, no matter their own embodiment and racial experience, is socialized and mal-formed by the racism of our country. There are not easy answers to how we can and should respond. But speaking truthfully about racism as a complex moral problem is a good step in the right direction. White Catholics can join Rob McCann, CEO of Catholic Charities Eastern Washington, in confessing our racism, acknowledging how our bias feeds racist systems, and working to eliminate it. This is the work that Ibram Kendi describes as “antiracism,” whereby one supports antiracist policies through one’s actions or expressing antiracist ideas (Kendi, chapter 1).

What does the Catholic Church teach about racism?

The Catholic Church teaches that racism has both personal and social/institutional dimensions; that racism violates justice and human dignity; that racism is a life issue; that the Church has been complicit in the evil of racism; that racist acts are sinful; and that racist acts are intrinsincally evil acts meriting consideration in determining how to vote.

See, for example:

- “Racism arises when—either consciously or unconsciously—a person holds that his or her own race or ethnicity is superior, and therefore judges persons of other races or ethnicities as inferior and unworthy of equal regard.” (Open Wide Our Hearts, 3).

- “”Racist acts are sinful because they violate justice.” (Open Wide Our Hearts, 3).

- “Every racist act—every such comment, every joke, every disparaging look as a reaction to the color of skin, ethnicity, or place of origin—is a failure to acknowledge another person as a brother or sister, created in the image of God.” (Open Wide Our Hearts, 4).

- “Racism comes in many forms… All too often, Hispanics and African Americans, for example, face discrimination in hiring, housing, educational opportunities, and incarceration. Racial profiling frequently targets Hispanics for selective immigration enforcement practices, and African Americans, for suspected criminal activity. There is also the growing fear and harassment of persons from majority Muslim countries.” (Open Wide Our Hearts, 4).

- “Racism can be institutional, when practices or traditions are upheld that treat certain groups of people unjustly. The cumulative effects of persons sins of racism have led to social structures of injustice and violence that makes us all accomplices in racism.” (Open Wide Our Hearts, 5).

- “The truth is that the sons and daughters of the Catholic Church have been complicit in the evil of racism… We also realize the ways that racism has permeated the life of the Church and persists to a degree even today… Acts of racism have been committed by leaders and members of the Catholic Church—by bishops, clergy, religious, and laity—and her institutions. We express deep sorrow and regret for them.” (Open Wide Our Hearts, 21-22).

- “Nationally, taking concrete action should include advocating for equality in how laws are implemented and advocating for moral budgets that reduce barriers to economic well-being, appropriate healthcare, education, and training.” (Open Wide Our Hearts, 24).

- “We affirm that participating in or fostering organizations that are built on racist ideology (for instance, neo-Nazi movements and the Ku Klux Klan) is also sinful—they corrupt individuals and corrode communities. None of these organizations have a place in a just society.” (Open Wide Our Hearts, 25).

- “We call on all members of the Body of Christ to join others in advocating and promoting policies at all levels that will combat racism and its effects in our civic and social institutions.” (Open Wide Our Hearts, 28).

- “Racism is a life issue.” (Open Wide Our Hearts, 30).

- “Some challenges have become even more pronounced. Pope Francis has continued to draw attention to important issues such as migration, xenophobia, racism, abortion, global conflict, and care for creation.” (Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship, 6).

- “Aided by the virtue of prudence in the exercise of well-formed consciences, Catholics are called to make practical judgments regarding good and evil choices in the political arena. There are some things we must never do, as individuals or as a society, because they are incompatible with love of God and neighbor. Such actions are so deeply flawed that they are always opposed to the authentic good of persons. These are called ‘intrinsically evil’ actions… Nor can violations of human dignity, such as acts of racism, treating workers as mere means to an end, … ever be justified.” (Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship, 21-23).

Evaluating Our Candidates

President Donald Trump is expected to speak each night this week at the Republic National Convention, but his campaign for a second term has already begun. Joseph Biden Jr. served as Vice President from 2009-2017 in two Obama administrations and accepted the nomination at the Democratic National Convention last week. Both Trump and Biden have experienced white privilege and the malformation of socialization in a racist society. But their records on race are significantly different.

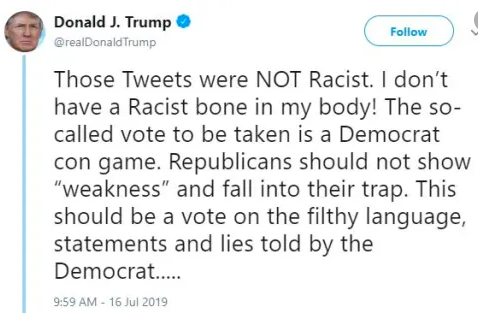

Donald Trump regularly uses Twitter for racist tweets that use dehumanizing language for non-whites. He incites fear of the migrant, fear of the ‘other,’ fear of anyone who is different. His strategy includes appeals to white nationalist groups, whom he re-tweets. After Charlottesville, he said there were “very fine people” on “both sides,” failing to hold white nationalists accountable to their platform of hate. He went on to label Haiti and African nations as “shithole countries” and referred to Mexicans as “rapists” and “drug dealers.” He tells Americans who don’t look like him to “go back” to the countries from which they came. (See Michael Luo’s piece here and the Time piece here). He called the coronavirus “kung flu” and “Chinese virus,” called racial justice demonstrators “thugs,” calls urban neighborhoods “disgusting” and called efforts to remove Confederate statues an assault on “our heritage.” More recently, Trump tried to appeal to white Suburban voters by telling them they won’t be “bothered” by low-income neighbors. When critics point out his racist comments, he either doubles down on them, lashes out at the critic, or makes self-serving claims, such as when he said “I’ve done more for Black Americans than anybody, with the possible exception of Abraham Lincoln.” Meanwhile, his party is engaged in voter suppression campaigns that disproportionately impact minority voters. Four years with President Trump has meant an assault of microaggressions, incendiary rants, and tweets that align with what the US bishops describe as discrimination, harassment of persons, a failure to acknowledge another person as a brother or sister, created in the image of God, and intrinsically evil, racist acts, so deeply flawed that they should never be tolerated.

Joe Biden’s record is different, both because he has been in public service for longer than President Trump and because when critics point out comments that are racist, he takes time to explain himself and apologize. Biden’s critics on the left will point out his role in shaping the 1994 crime bill, which focused on reducing violent crime and included the “three strikes” sentencing rules, funding for prisons and community policing, and the Violence Against Women Act. Critics argue that the law led to mass incarceration of young men of color, and Biden has discussed the law’s impact along the campaign trail including during the primaries. Biden would also point to other aspects of his decades in leadership in Congress, including his bipartisanship and friendship with Senator John McCain. His work in the Obama White House led to policies that sought to address systemic injustice, reduce gun violence, address violence against women, and secure health care for all. As he looks ahead now, Biden’s racial equity plan recognizes the systemic and long-term impacts of racism in US society, and proposes a way forward to make our country more equitable. In his DNC speech, Biden drew on themes of hope and fairness: “United we can, and will, overcome this season of darkness in America. We will choose hope over fear, facts over fiction, fairness over privilege.” He went on to say that America is ready to, in the words of John Lewis, “lay down ‘the heavy burdens of hate at last’ and to do the hard work of rooting out systemic racism.” A President cannot do this alone, but this is a step in the right direction of what the US Bishops call us to do when they tell us to advocate for and promote policies at all levels that will combat racism and its effects in our civic and social institutions. (Open Wide Our Hearts, 28).

Questions for the discerning voter to consider in prayer before voting

The USCCB Open Wide Our Hearts Study Guide encourages Catholics to engage in an examination of conscience by asking these questions:

- Have I fully loved God and fully loved my neighbor as myself?

- Have I caused pain to others by my actions or my words that offended my brother or my sister?

- Have I done enough to inform myself about the sin of racism, its roots, and its historical and contemporary manifestations? Have I opened my heart to see how unequal access to economic opportunity, jobs, housing, and education on the basis of skin color, race, or ethnicity, has denied and continues to deny the equal dignity of others?

- Is there a root of racism within me that blurs my vision of who my neighbor is?

Voters still have 72 days to prioritize this discernment in conscience. A voter must make a proportionate judgment after careful discernment and the weighing of values and disvalues.

As a white person in a racist society, I also find myself asking:

- How can I use my vote to serve others?

- How can I ensure that my vote creates more opportunities for students of color, Black workers, Latinx mothers?

- How will my vote further the common good?

Trackbacks/Pingbacks