This is a guest post by Lucas Briola, The Catholic University of America

On Friday, October 27, I found myself in a packed room with over 50 Protestant clergy at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary for a morning-long session on pastoral responses to the present opioid crisis. The epidemic has hit my home region of Southwestern Pennsylvania particularly hard for the past few years and has just recently begun to receive the national attention it deserves.

The conference grew out of a two-year effort to respond to the questions and anxieties of local pastors. I was in part representing St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, a Catholic parish in blue-collar Carnegie, PA, which hoped to strengthen its already-existing substance abuse ministry. Personally, I have been struck by how little theological attention the current crisis has engendered, and so, as a budding theologian, I hoped to learn how I could contribute to redemptive solutions.

The day began with an address from Lee McDermott, currently a Presbyterian pastor in neighboring Fayette County who had previously worked for twenty years in addiction treatment and recovery. When he first began practicing ministry, Lee shared much of my own current perplexity. He was shocked that given the prevalence of addiction, churches spent little time talking about it. As he put it, “The church was simply silent…and, more importantly, it was missing out on some wonderful stories.” After assuring all the pastors in the room that at least someone in their congregations struggled with addiction, Lee suggested the church could help in at least two ways. First, it should provide spaces for healthy relationships; for instance, churches should foster more collaborative relationships with groups like Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous. Second, churches can provide much-needed spiritual sustenance; those struggling with addiction, he reported, often doubt that God’s love does indeed truly extend to them. Churches can thus keep the needed conversations about drug abuse focused on compassion, forgiveness, and redemption instead of condemnation, punishment, and shame. Pastors and addicts alike,  Lee concluded, need to remember that they are all indeed on a journey, whether they like the starting point or not.

Lee concluded, need to remember that they are all indeed on a journey, whether they like the starting point or not.

Dave Lettrich, a senior M.Div. student at the seminary who founded a fascinating program called “Bridge to the Mountains” earlier this year, spoke next of his own experience in ministering to people struggling with addiction on the streets of Pittsburgh. He worried that ministers too often focus exclusively on recovery, which can inadvertently push people away from receiving the pastoral care they need. Dave stressed encountering people first as they are, and so he spent most of his time showing pictures of, telling stories about, and expressing a profound love for the various people he has served on the streets, many of whom have died over the past six months from overdoses. He also brought Nikki, a particularly inspiring woman who happened to be a recovering addict released from prison just the previous week. She spoke of her own struggles (nonchalantly mentioning that she herself had “brought back” over twenty people) and the love and hope Dave’s ministry has provided her. (She also recommended a book, American Junkie, for providing an especially helpful glimpse into the life of one struggling with and recovering from addiction.) Like Lee, both Nikki and Dave spoke of the need for the church to be a place of unconditional, indiscriminate, and vulnerable love, ready and present to be a resource only when those struggling with addiction are actually ready to take steps towards recovery.

Sue Washburn, a Presbyterian pastor in Mt. Pleasant and interim editor of Presbyterians Today, followed and spoke on congregational and liturgical responses to addiction. Like Lee, she urged that we needed to raise consciousness about and remove stigmas around the opioid crisis. She urged pastors to be intentional in incorporating the voices of those struggling with addiction in prayers and sermons. She pointed to resources like the Big Book of AA and The Life Recovery Bible, along with stories of redemption from various news stories and conversations about addiction. She spoke of designing special services of healing and Lenten/Advent devotionals dedicated to addiction and recovery. Finally, especially interestingly, Sue suggested that pastors should embrace a “black and white theology.” She observed that while mainline Protestant congregations have largely embraced shades of gray when it comes to questions of morality, a clearer stress on right and wrong—akin to the theology of Evangelical churches—could actually be more helpful for dealing with addiction.

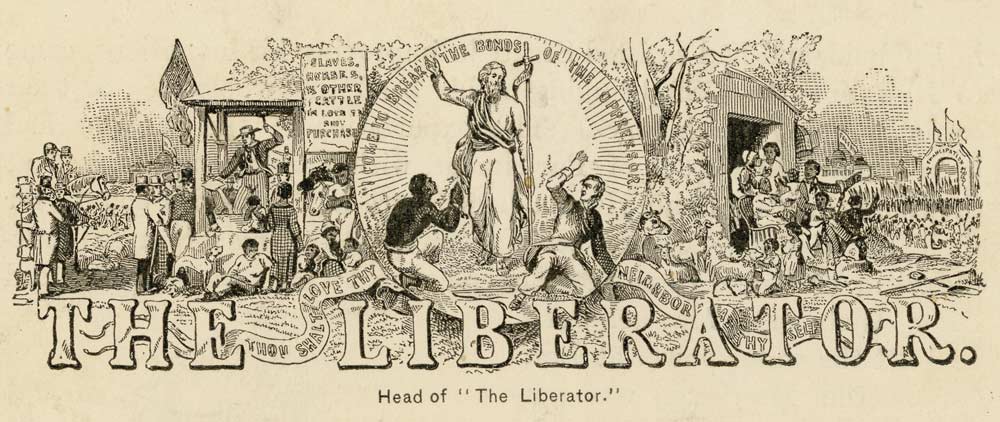

Sue’s talk led into an abbreviated “service of healing and hope” held in the seminary’s chapel. After an opening prayer (pictured here), we prayed Psalm 23 aloud (“The Lord is my shepherd…”). Two people recovering from drug addiction gave their testimonies of struggle and hope, punctuated by a reading of Isaiah 46:3-5, reminding us of God’s ongoing comfort to the lonely and exiled. After a period of silence, we were invited to come to the front of the chapel, write on a black cross the name of a loved one struggling with addiction or dead from an overdose (pictured at the beginning of this post), and light a candle in that person’s memory, all the while as we rhythmically chanted a Taizé hymn. Afterwards, we prayed the Serenity Prayer together and concluded by singing an adapted version of Amazing Grace. The striking juxtaposition of grief, slavery, liberation, and joy throughout made a dry eye rare by the end of the service.

Finally, as we moved to lunch, we met with our respective county health representatives in an open forum. The meeting confirmed a recurring theme throughout the day’s talks—since it remains a practical problem, churches, county agencies, and non-profits alike need to work together to solve the opioid crisis. (Incidentally, no mention was made of national solutions to the problem, perhaps due in part to the frustrations surrounding the most recent reports of political chicanery and corruption.) The day provided much hope, showing that congregations are beginning to find their voices. As death tolls and broken families rise by the day, one can only hope that us theologians begin to end our relative silence and contribute to this conversation ourselves.