Readings: 1 Samuel 16:1b, 6-7, 10-13a; Psalm 23:1-3a, 3b-4, 5-6; Ephesians 5:8-14; John 9:1-41.

In so many ways, today’s readings have to do with allowing Jesus to teach us to see and read the world around us, to let God’s light illumine that world and its future, and to put aside the tricks we play on ourselves and each other to avoid seeing the world in God’s light.

Samuel must lay aside his own impressions of who might be God’s anointed. “Not as man sees does God see,” for “the Lord looks into the heart.” To pray Psalm 23 is to learn to rest with trust upon God’s providence—and to do this not in some made-up Disneyland in our heads but in the real world with its serious dark valleys and enemies. It is to let God’s light show us that world as a place where God can be trusted completely. And as we read in Ephesians, children of the light also participate in the goodness and truth that God’s light brings to the world’s dark valleys. They “try to learn what is pleasing to the Lord.” They bear appropriate fruit. They learn to speak the truth and expose the “fruitless works of darkness” precisely by reference to the light that has come into the world.

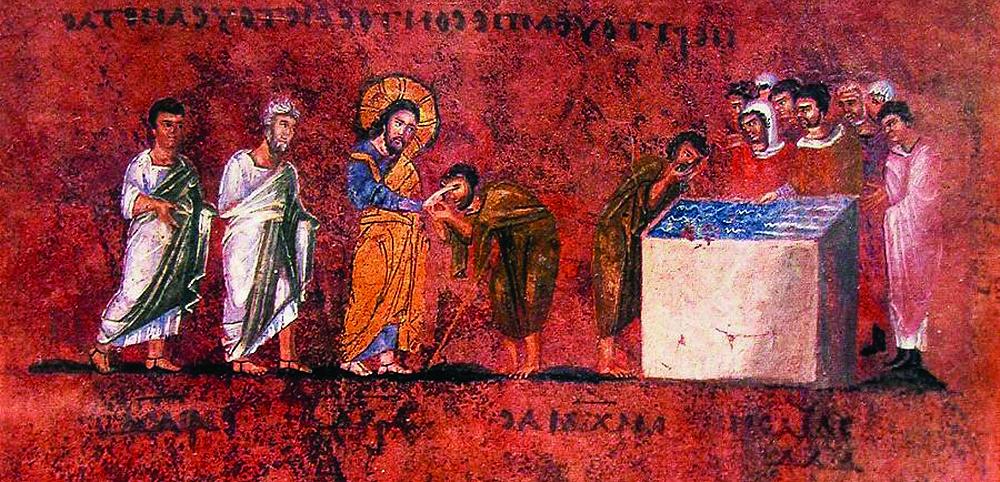

In John 9, Jesus is not only the light of the world, but also the one who paradigmatically can and does see. The action begins when Jesus sees a man blind from birth. Others notice and interact with the blind man too, of course. But they do not take notice of him within the proper frame of reference.

To the disciples, the man’s blindness is a tragedy to be explained from a safe distance. On either option they pose to Jesus, the man’s predicament results from other people’s sins. It has nothing to do with the disciples. They can take notice of the man to the point of becoming uncomfortable and engaging in theological rationalizations. But they cannot see him as someone calling upon their personal responsibility.

Notice Jesus’s correction of the disciples: “Neither he nor his parents sinned; it is so that the works of God might be made visible through him.” Jesus sees the blind man as someone who can receive God’s loving mercy and who can find a positive place in the works of God. Jesus is ready to respond immediately (at this very moment, “while it is day,” even though it is a Sabbath) and invest himself generously in the work of coming near to this blind man and giving him life. Jesus’s attention yields the same intimate involvement that we see in the Lord God’s acts of creation in Genesis 2.

The works of God will be made visible in the healing itself (“it is unheard of that anyone ever opened the eyes of a person born blind”). But they are also visible in what the healed man is becoming more generally. Although the explanation of the pool’s name in verse 7 attests first of all to Jesus’s own identity as “sent” by the Father, it is impossible to avoid its relevance to the person Jesus healed. That man has been freed to share in Jesus’s vision and to see others with a similarly trusting and solicitous posture. He is already becoming an active witness to the light well before he can provide a full account of who has healed him or a slam-dunk response to the threatening questions posed by others. On the other hand, we can’t fail to notice his patience with the Pharisees: Even after they have ridiculed him and treated him as fodder for their own rationalizations (and even though they will continue to do so), he nevertheless proceeds to give them an even fuller explanation (9:30-33). This likely has something to do with the fact that his position is far more vulnerable than that of the Pharisees. But it stems primarily from his response to Jesus and what this exposes about those questioning him: “This is what is so amazing, that you do not know where he is from, yet he opened my eyes.” The works of God are becoming visible not only in that the man is no longer physically blind, but also in his becoming a child of the light.

Like the disciples, the Pharisees in this story waste what vision they have articulating questions and statements that shield them from an intimate, trusting, and solicitous response to the human being in front of them. But aspects their own situation strike me as particularly important.

First is the ad hominem reply with which they excuse themselves from engaging the healed man’s thoughtful argument: “You were born totally in sin, and are you trying to teach us?” (v.34). This moment in John 9 troubles me especially deeply. It forces me to remember just how many of the conversations I either notice or take part in over the course of a week (in whatever setting) take this basic form in some way or another. It is decided ahead of time, often by a group and perhaps over time (see again verses 15-17!), that someone’s statement or argument is wrong in some important, perhaps fundamental way—and that this person’s error overrides any attention we could potentially devote to whatever other light this person may shed on the topic at hand. The point of replying to this person is simply to explain to her (and to others, and to ourselves) why she is wrong. Insight is praised among the group when it clarifies and deepens this rationalization. It may or may not be to our credit that we usually outdo the Pharisees in the time and energy we invest building our walls against a trusting, intimate, and solicitous engagement. We have devised more sophisticated ways of dismissing others as “sinners.”

I don’t take this to be news. Many of us admit there is a growing problem with how we do or do not engage intellectual or cultural others as persons. At least from what I can see, such patterns of defensive rationalization are more the norm than the exception in the communicative culture (or family of communicative cultures) in and through which most of us stay in touch with our present world. Many would agree that this is a problem for a variety of reasons. What is interesting about John 9 is how it exposes a distinctly theological problem with this pattern of behavior. It is not just ‘bad for democracy.’ It strikes directly against my ability to let Jesus’s light shine in my life. It means that I do not yet know how to see other people as the Lord sees them.

There is a lot to be said, then, for exploring what it would look like to emulate Jesus’s vision of other people within the contexts I am describing. But to stop here would be to lose sight of something very important. After all, Jesus seems to have less time and attention for the Pharisees themselves. They, unlike the blind man, should know better! “If you were blind, you would have no sin; but now you are saying, ‘We see,’ so your sin remains.” It can be immensely tempting, then, to imagine that our emulation of Jesus in this respect gives us a blank check to treat intellectual or cultural others in just the way Jesus treats the Pharisees. That person who is wrong should know better. She neither needs nor deserves my vulnerable, solicitous personal response. What she needs and deserves is to be exposed as blind. One she admits her blindness, then I might consider treating her as Jesus treated the blind man.

What this approach misses is that our own situation may often resemble the blind man’s more than it resembles Jesus’s. Once healed, this man does become a witness. But his words consistently match how much he does or does not know about Jesus or about the world. It may not be an accident, then, that in this story the fullest engagement with the Pharisees belongs to the healed man rather than to Jesus—and this last conversation between them may tell us much more about what it means for the rest of us to strive after Jesus’s way of seeing and engaging people as people.

Like the blind man in this story, the rest of us have much to learn even after Jesus has opened our eyes and sent us as witnesses. We have much to learn about the one who has healed us, about ourselves, our friends, our enemies, and the cultural landscape in front of us. We are tempted to claim we already have a basically sufficient account of what is wrong with the world and why that other person is wrong or “blind.” On the one hand, this strikes me as an immensely naïve posture to take up before the slew of political, economic, cultural, technological, and religious problems with which we must contend. On the other hand, it threatens to suppress the derivative nature of our witness to the light. Multiple perspectives in the broad tradition of Christian moral theology attest to the way in which our prior formation and deliberation can never fully replace listening to God and receiving God’s light here and now. Karl Barth distinguished between our always-preliminary process of moral deliberation and our listening to God’s command in the immediate present. Thomas Aquinas made a somewhat similar point when he argued that infused prudence—the prudence aimed at the perfect realization of our final end in the beatific vision of and union with God—must be exercised with the gift of counsel, i.e., the disposition by which we become “amenable to” the promptings of the Holy Spirit. We are always somehow unable to fully grasp what is in front of us, always in need of listening to God over and beyond what we have already gathered or received:

Since…human reason is unable to grasp the singular and contingent things which may occur, the result is that “the thoughts of mortals are fearful and our counsels uncertain” [Wisdom 9:14]. Hence, in the research of counsel, the human being needs to be directed by God who comprehends all things. And this is done through the gift of counsel, whereby human beings are directed as though counseled by God, just as, in human affairs, those who are unable to take counsel for themselves, seek counsel from those who are wiser (ST II-II.52.1 ad 1).

No amount of preparation can replace my constant need to let Jesus teach me how to see and read each new immediate present before me. Our encounters with those we consider blind in a blameworthy way (who we think should have known better) must, it seems, reflect this openness to what God may teach us in our immediate present. And I’m not really sure how that is possible when we assume from the start that our engagement with that other person is aimed principally (if not only) to explain why she is wrong.