When the Obama administration threatened to carry out military strikes against the Syrian government after the use of chemical weapons in the town of Ghouta on August 21, Catholic theologians and ethicists issued a flurry of articles arguing that a military intervention in Syria would not meet the criteria of the just-war theory (see my own work here, and others’ here, here, here, here, here, and here, among others).

On September 4, however, the German diplomat Wolfgang Ischinger published an article in the German magazine Der Spiegel, entitled “Syrian Hell: Why We Must Not Forget the Lessons of Bosnia.” Ischinger argues that while opponents of intervention in Syria look to Afghanistan and Iraq for lessons, the UN and NATO intervention in Bosnia in the early 1990s provides more meaningful lessons for Syria, namely that military intervention can be a successful response to a humanitarian controversy and can help make a peace agreement possible. This argument has been picked up by several Catholic authors, including Mark Silk, Michael Sean Winters, and E.J. Dionne. This is understandable because, as Winters and Robert Christian have recently pointed out, the responsibility to protect (R2P) doctrine endorsed in recent years by both the Vatican and the United Nations does justify the limited use of force in certain humanitarian crises, and Bosnia represents a successful, if belated, example of such intervention.

Although there are significant similarities, from an ethical perspective, between the conflicts in Bosnia and Syria, there are also important differences that render intervention in the former case justified but not in the latter. First, during the time of the conflict in Bosnia, Russia was weak. Second, the conflict in Bosnia was primarily about territory. And third, the Bosnian conflict had little risk of wider escalation. I will explain each of these differences in more detail, but first it will be useful to provide a brief history of the Bosnian conflict and the intervention of the UN and NATO.

The Conflict in Bosnia

The republics of the former Yugoslavia

Communist Yugoslavia had a federal system consisting in the relatively autonomous republics of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Serbia, and ethnic tensions were relatively minimal. After the death of President Tito, however, these tensions became more pronounced; Slobodan Milosevic, the communist leader of the republic of Serbia, sought a more dominant role for Serbia within Yugoslavia. After the fall of communism in the rest of Eastern Europe, the various Yugoslav republics held multi-party elections in 1990. In Slovenia and Croatia, these elections pushed the republics toward greater autonomy and eventually declarations of independence in 1991. Conflict broke out between these two republics and Serbia in 1991, and while Slovenia quickly won its independence, the war in Croatia carried on, mainly because of the substantial Serbian population within Croatia.

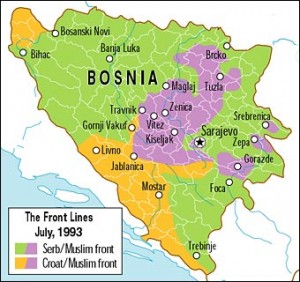

Meanwhile, in October of 1991, the republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared its independence. Bosnia, like Croatia, had a substantial Serbian population, however, making up 32.5% of the population. Bosnian Serb leaders responded by creating an autonomous Serbian republic (Republika Srpska) within the Serbian-majority areas of Bosnia, with the eventual goal of uniting with Serbia. A Serbian army, made up of remnants of the disbanded Yugoslav army, sought to gain effective control of this territory, battling the Bosnian army. They also began the process of ethnic cleansing, killing or removing non-Serbs from territory claimed for Serbs. Croats also made up 17% of the population of Bosnia, and they established the republic of Herzeg-Bosnia. Bosnian Croats battled both Bosnian Serbs and Muslim Bosniaks as Croatia itself also continued to fight for its independence. The Bosnian army was besieged on two fronts, by Croats in the west and Serbs in the north and east, throughout 1992 and 1993. A turning point came in early 1994 when the Bosnian Croats and the Bosnian army signed a cease fire, focusing their combined efforts against the Bosnian Serbs.

A map of the Bosnian conflict in 1993

The international community became involved in the conflict relatively early. In 1991 the UN Security Council had already put in place an arms embargo as a result of the conflicts elsewhere in Yugoslavia, but this only disadvantaged the Bosniaks, as the Serbs had access to the former Yugoslav army’s equipment, and the Croats were able to smuggle in arms along their coast. The Security Council authorized the creation of the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) in February 1992 to help keep the peace after a cease fire was signed in the Croatian war of independence. In June of that year UNPROFOR’s mission was extended to ensuring the secure arrival of humanitarian aid to Bosnia. Diplomatic efforts at establishing peace in the early years of the conflict, such as the Carrington-Cutileiro peace plan and the Vance-Owen peace plan, ended in failure. As the war continued, the UN Security Council approved a no-fly zone over Bosnia, enforced by NATO, in February 1993 and in May authorized the use of force to protect so-called “safe areas.” NATO did not begin military strikes, however, until February of the next year. These limited air strikes, combined with the UN forces on the ground, proved ineffective, and it was in July 1995 that Serbian forces carried out the Srebrenica massacre, in which over 8,000 Bosniak men were killed, despite the presence of a UNPROFOR unit in the city. In late August, NATO forces began a much more comprehensive air campaign, Operation Deliberate Force, which forced Bosnian Serb forces to withdraw and brought the Serbs to the negotiating table. So those who look to Bosnia as an analogy for intervention in Syria are correct that military intervention put an end to a humanitarian disaster, but there are still significant differences between the two cases.

1. Russia Was Weak

In 1989 the Soviet Union lost its Eastern European satellites, and after the failed 1991 coup against Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union itself dissolved as several republics gained their independence. The newly democratic Russia, under the leadership of Boris Yeltsin, rapidly began implementing liberalizing economic policies, known as “shock therapy.” The result of these policies, however, was a severe economic downturn that lasted throughout most of the 1990s. In 1994, Russia also became bogged down in the First Chechen War as it sought to prevent the independence of the republic of Chechnya. Also during the early 1990s, Russia was actively seeking to be integrated into the liberal international order dominated by the United States. This then was a brief, unique period in which sustained U.S.-Russian cooperation was possible because Russia had neither the means nor the desire to counterbalance the global position of the U.S. This cooperation was evident in the Bosnian conflict. Russia played a significant role in negotiating the eventual peace settlement and also supported all U.N. resolutions concerning the conflict, including those authorizing the use of force.

Beginning in the late 1990s, however, Russia has become more assertive and relations between Russia and the West more confrontational. This has been evident in Russian opposition to NATO’s military intervention in Kosovo in 1999 and to the war in Iraq in 2003. Russia is threatened, in particular, by the expansion of NATO and the European Union into eastern Europe, and also seeks to regain its role as a global power that it held during the Cold War. A stronger economy, fueled by higher oil prices, has allowed Russia to take this more assertive role.

Clearly Russia has taken a central role in the conflict in Syria. Russia has close commercial and military ties with Syria, including a naval facility in the town of Tartus, and has stymied international efforts to resolve the conflict. Russia has signaled, however, that it is willing to support peace negotiations, particularly if the possibility of Syrian President Bashar Assad playing some role in a future Syria is assured. Russia’s support for Assad and opposition to U.S. intervention, however, makes the sort of intervention possible in Bosnia much less plausible in Syria. Whereas in Bosnia military strikes helped precipitate peace negotiations, a U.S. military strike in Syria would more likely render them impossible by alienating Russia, if not invite further Russian intervention into the conflict on the side of the government.

2. The Bosnian Conflict was Primarily About Territory

The NATO intervention in Kosovo shows that humanitarian intervention can succeed even in the face of Russian opposition, but other factors make success in Syria less likely. One of these is the issues at stake. The conflict in Bosnia was primarily about territory. Bosnian Serbs and Croats sought to gain control of the territory in which their groups were the majority and ultimately to merge that territory with Serbia and Croatia, respectively; the Bosnian government in turn sought to preserve its territorial boundaries. Although both the Serbs and Croats were motivated by an extreme nationalism that resulted in the dehumanization of those who were different, carried out through atrocities against the Muslim Bosniaks, the conflict was never a war of extermination; for example, the sinister Graz Agreement of 1992, in which Serbs and Croats agreed to divide up Bosnian territory, still envisioned a Bosniak homeland. The focus on territory enabled all sides to consider the continued existence of the other as an acceptable outcome of the conflict, facilitating peace negotiations and the Serbian withdrawal after NATO intervention (in fact, the Republika Srpska persists as an autonomous entity making up nearly half the territory of Bosnia). The Syrian conflict, however, is not primarily about territory, but rather survival and ideology.

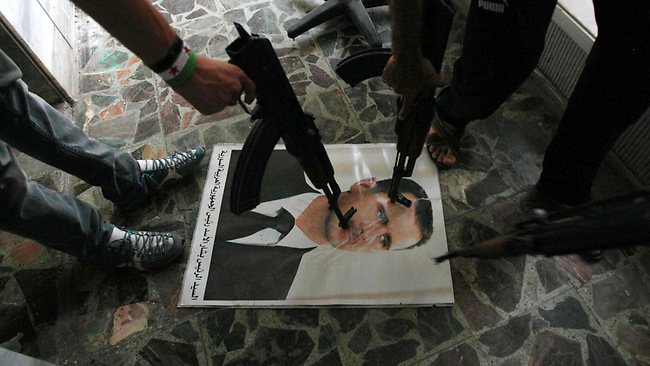

Syrian rebels make their intentions clear.

a. The Syrian conflict is a true civil war in which two (or more) factions vie for control of a single state. A civil war is by its nature a zero sum game in which victory for one side is incompatible with the political (if not physical) survival of the other. Bashar Assad need only look to the fate of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya to see what awaits him if he loses to the rebels, and the rebels know they will meet a similar end should the government gain the upper hand. In a sense this desire for survival might provide an incentive for accepting a negotiated political settlement, but the nature of civil war also makes such a settlement much more difficult to attain and maintain. Without a plausible peace settlement on offer, U.S. intervention is more likely to encourage Assad, unlike the Serbs, to double down rather than come to the table.

b. The Syrian conflict is also more ideological than the Bosnian conflict. Again, while the Bosnian conflict was primarily about territory, the cleavages in the Syrian civil war reflect the two most important struggles in the broader Middle East, those between secular nationalism and Islamism, and between Sunni and Shi’a Islam. Assad’s Ba’athist regime is, after the fall of Saddam Hussein in Iraq and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, one of the last bastions of secular Arab nationalism. The rebels, on the other hand, are increasingly dominated by Islamists who seek to impose a political order based on the tenets of Islam. Although the regime itself is largely secular, the Syrian government is dominated by the Alawite minority, a branch of Shi’a Islam. The rebels, on the other hand, are predominantly Sunni. Therefore the conflict in Syria, unlike Bosnia, cannot be solved by dividing up territory because it is a conflict of differing conceptions of the political order that should govern a single territory. Given these considerations, it seems unlikely that U.S. military intervention could contribute to a meaningful resolution of these issues and in fact might exacerbate them, given the centrality of anti-Western and anti-American views in the Arab world.

3. The Bosnian Conflict Had Little Risk of Wider Escalation

Perhaps most importantly, U.S. military intervention in Syria is more likely to lead to the escalation of the conflict rather than its resolution because the issues at stake are not limited to Syria but rather cut across the entire Middle East. The Syrian government is already being supported by Iran, the dominate Shi’a power in the Middle East, and Hezbollah, the Shi’a militia in Lebanon. The rebels in turn are supported by the Sunni Gulf States, such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Sectarian conflict is also breaking out again in neighboring Iraq. A U.S. intervention on the side of the rebels could invite even more pronounced action by Iran, potentially drawing the U.S. (and Israel) deeper into the conflict. Looking at things geostrategically, the Middle East is also in the midst of a re-alignment partially caused by the vacuum created by the defeat of Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Iran clearly seeks to become a regional hegemon through its proxies Syria, Hezbollah, and Shi’a groups in Iraq. After its efforts at joining Europe have been indefinitely postponed, Turkey has turned toward attempting to become a major player in the Middle East. Egypt, although consumed by its own domestic problems, has the potential to play an important role in the region, as well. If U.S. intervention provokes a response from Iran, this could in turn lead to Turkey becoming involved, for example, as the conflict spirals out of control into a regional war.

Turkish soldiers mobilized near the Syrian border, October, 2012

This danger was not present in Bosnia. The Bosnian Serbs and Croats were supported by Serbia and Croatia, respectively, and mujahedeen from across the Muslim world came to fight with the Bosniaks, but ethnic nationalism has such narrow appeal that other nations were not drawn into the conflict. The major powers with an interest in the conflict—the United States, the nations of western Europe, and Russia—were on the same page. The low risk of escalation enabled the UN/NATO intervention to have its intended effect, the cessation of hostilities and the initiation of peace negotiations. For that reason, Bosnia serves as an example of when humanitarian intervention can be morally justified, but Syria, because of the different context, is not such an example. Given these impediments to a successful intervention, the path to peace in Syria will have to be different than that for Bosnia. The most likely solution will involve the U.S. and Russia agreeing on a basic framework, including the possibility of Assad continuing to play some role in the government of Syria, that would serve as the basis for a peace conference bringing together representatives of the government and the rebels. Then, hopefully, this settlement could gain the backing of the UN Security Council, and only then, if the settlement is not implemented, could the Security Council threaten an armed intervention with widespread international backing. This plan is not assured of success, but I believe it has a greater chance of succeeding than U.S. military intervention, even of a limited scope, without further diplomatic discussion.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks