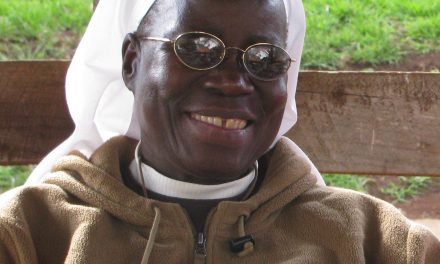

Dorothy Day and H. E. Reimer Jr. at McGill, 1940

Dorothy Day and H. E. Reimer Jr. at McGill, 1940

As citizens of the United States (indeed, of the world) continue to debate the morality and legality of strikes in Syria, I find myself thinking through the arguments for and against, and reflecting on them in the light of faith. I listened to President Obama tonight, and to some of the commentary on MSNBC afterwards, and have read a variety of sources online (including the CMT post here by Tobias Winwright). In many ways the conflict I feel in my discernment is represented in this old photograph.

That’s my grandfather, Henry Edward Reimer, Jr., on the left, with his clipboard, paper, and pen. He is looking dapper in his leather jacket, and respectfully interviewing the guest speaker who had come to his high school. On the right is Dorothy Day, the ash of her cigarette nearly making a mess. She looks weary from her travels (and maybe from his questions!). I’m pretty sure that this picture was taken in January, 1940. First, because Mobile, Alabama, is too hot most of the year for a jacket like the one my grandfather is wearing, and second, because I found a record of Dorothy Day’s travels in Alabama in 1940 here, where she explains that Bishop Toolen invited her to speak in various schools. She and her daughter were staying with the Missionary Servants of the Most Blessed Trinity, next door to the Cathedral. Dorothy Day expressed gratitude for the hospitality of the sisters, especially Sister Peter Claver, and she describes her work among labor unions and her hopes for establishing a cooperative farm and social services for seamen.

Before my grandfather died, he told me that he had interviewed Dorothy Day, but that he was not impressed by her anti-war activism. I still have not been able to find the article he wrote for his high school newspaper, but I will have to try harder. I’m more curious now.

My grandfather supported U.S. involvement in World War II and saw that as totally consistent with his identity as a Catholic Christian. He had friends who lost their lives in combat. Late in life, any time he wanted to emphasize the reality of evil in the world, he would mention Hitler. Even with the surname Reimer, there was no question in his mind that Nazi Germany was a threat to civilization and that World War II was a just war. He thought pacifists like Dorothy Day were naive, foolish, and unpatriotic. My grandfather considered himself a realist. From his perspective, sometimes in order to do the right thing, you had to stand up for what you believe in, and even use force to be sure that good triumphed over evil. While he never used the phrase himself, my grandfather’s political and religious ideology is similar to what Catholic ethicist Mark Allman describes as Christian Realism in his book, Who Would Jesus Kill? (St. Mary’s Press, 2008). Allman describes the political theology of Reinhold Niebuhr, who critiques Christian pacifism for failing to take human sinfulness seriously. Allman summarizes this position:

Niebuhr argues that Christian pacifists have an overdeveloped confidence in human goodness; they believe that the gospel law of love is enough to rid the world of violence and evil. For Niebuhr, such an approach is not only naive, but heretical. The gospel also contends that sin is a fact of life in an unredeemed world. To claim that all we need is love is tantamount to saying we do not need God and that Christ’s sacrifice on the cross was unnecessary….

He argues that Christian pacifists labor under an overly optimistic understanding of human nature (that is, “the Renaissance faith in the goodness of man”), while the traditional Christian understanding of human nature is that we are sinful creatures living in an unredeemed world…

Here Niebuhr stands with Augustine, who argued centuries earlier that sometimes the use of force is a necessary evil to avoid an even greater evil. For Christian realists, pacifism is an ideal, a utopian hope that is unattainable through human efforts (107-110).

But what would Dorothy Day say? She did not think her anti-war activism was naive or cowardly. In 1936, Day wrote in The Catholic Worker:

We oppose class war and class hatred, even while we stand opposed to injustice and greed. Our fight is not “with flesh and blood but principalities and powers.” We oppose also imperialist war. We oppose, moreover, preparedness for war, a preparedness which is going on now on an unprecedented scale and which will undoubtedly lead to war…

Do we believe we help any country by participating in an evil in which they are engaged? We rather help them by maintaining our own peace. It takes a man of heroic stature to be a pacifist and we urge our readers to consider and study pacifism and disarmament in this light. A pacifist who is willing to endure the scorn of the unthinking mob, the ignominy of jail, the pain of stripes and the threat of death, cannot be lightly dismissed as a coward afraid of physical pain.

A pacifist even now must be prepared for the opposition of the next mob who thinks violence is bravery. The pacifist in the next war must be ready for martyrdom.

We call upon youth to prepare!

Was my grandfather part of the mob-mentality that equated violence with bravery? Or was he defending liberty and justice for all, even to the point of the greatest sacrifice? Was he too dismissive of pacifism, or are pacifists working from flawed assumptions?

In June of 1940, six months after the above picture was taken, Day explained that The Catholic Worker was opposed to U.S. involvement in World War II:

Many of our readers ask, “What is the stand of the CATHOLIC WORKER in regard to the present war?” They are thinking as they ask the question, of course, of the stand we took during the Spanish civil war. We repeat, that as in the Ethiopian war, the Spanish war, the Japanese and Chinese war, the Russian-Finnish war–so in the present war we stand unalterably opposed to war as a means of saving “Christianity,” “civilization,” “democracy.” We do not believe that they can be saved by these means.

Her rationale is explicitly theological:

But we consider that we have inherited the Beatitude and that our duty is clear. The Sermon on the Mount is our Christian manifesto…

Instead of gearing ourselves in this country for a gigantic production of death-dealing bombers and men trained to kill, we should be producing food, medical supplies, ambulances, doctors and nurses for the works of mercy, to heal and rebuild a shattered world. Already there is famine in China. And we are still curtailing production in agriculture, thinking in terms of “price,” instead of human needs. We do not take care of our own unemployed and hungry millions in city and country, let alone those beyond the seas. There is prejudice in our own country towards Jews, Negroes, Mexicans, Filipinos and others, a sin crying to Heaven for punishment.

In reading this today, I was struck by the similarity between Day’s analysis and so much of the commentary I’ve heard on the news. Why do we think we can export peace in the Middle East when we can’t even control the death toll in Chicago or New Orleans? Look at the unemployed and hungry here in our own country, the fear of the immigrant: “a sin crying to Heaven for punishment.” Day follows a radical Jesus: the Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount. What would our policy on Syria be if we privileged the Jesus of Matthew’s Gospel, chapter 5?

But then I hear my grandfather, asking me if I want to live in a world where bad guys like Bashar al-Assad can use chemical weapons without penalty. With power comes responsibility, my grandfather would say. When you have the military strength of the United States, backed by our economic and diplomatic assets, you have an obligation to defend human rights around the world, to hold dictators accountable to justice, even a human view of justice.

I find this view compelling. Yes, there should be penalties for human rights violations. Yes, there should be justice! But then the questions come: Should I trust that my elected leaders have sufficient evidence for the claims they make? And why do we think we can “send a message” to Assad by killing more Syrian civilians (which is inevitable, and it is best to be honest about that at the outset). And why do we think we can do this without “boots on the ground” or a huge financial investment to provide for the refugees who will need protection? And who are the good guys in this conflict, anyway? Besides us, I mean. Wait. What makes us good? Surely it isn’t just that we have more military capability. No, we are defending the dead children who foamed at the mouth. No thank you, Mr. President, I don’t want to watch the video on youtube. I believe you when you say that it is terrible and tragic. But since we can’t bring those children back from the dead, do we really think that bombing the weapons in their country and weakening their leader is justified?

And what kind of world do I want to live in anyway? I re-read Dorothy Day’s “Our Stand” on the meaning of love for the Christian disciple:

We are urging what is a seeming impossibility–a training to the use of non-violent means of opposing injustice, servitude and a deprivation of the means of holding fast to the Faith. It is again the Folly of the Cross. But how else is the Word of God to be kept alive in the world. That Word is Love, and we are bidden to love God and to love one another. It is the whole law, it is all of life. Nothing else matters. Can we do this best in the midst of such horror as has been going on these past months by killing, or by offering our lives for our brothers?

It is hard to write so in times like these when millions are doing what they consider their duty, what is “good” for them to do. But if the Catholic press does not uphold the better way, the counsels of perfection will be lost to the world.

There are many who consider that we are approaching the end of the world, but what are two thousand years in the history of the world? We are still in the beginnings of Christianity. It is true that we are at the end of an era, and we are probably seeing the death throes of capitalism.

“Just as slavery was only put down after hundreds of years of labor by Christian men, so war will never be done away with, or even limited, but by an army of Peace workers who never cease their labors.”

She offers a “better way,” a more challenging way, a counter-cultural way. Don’t settle for the assumption that war is inevitable. Witness to something greater, to a world of peace for everyone. And yet, don’t be a jerk about it. At the end of “Our Stand,” Day concludes by encouraging readers not to judge the just war folks who are making difficult decisions in conscience. Instead, focus on your own sanctification:

It is good to conclude with the words of Father Stratmann:

“No young man should consider himself superior to his companion who obeys the call to arms. Yes, he may be very much his inferior for there is a poor, feeble, unmanly pacifism without any strength or greatness, a compulsory pacifism from bodily weakness, or a sham pacifism from cowardice. Such are contemptible and it gives one food for thought that one of the young men of the other camp, Max Boudy says: ‘I have never yet found a pacifist whose pacifism inspired him with such inner beauty as I have found in several men for whom war, under certain circumstances, was a reasonable, justifiable, if tragic necessity.’ Such remarks must be taken seriously. They impose inner and outer obligations. If it is not to be a bloodless intellectualism or a weak, cowardly quietism, or a luxurious epicureanism–pacifism must lay very great stress on bodily discipline, on culture, on bodily and mental development.

“More than all, he who opposes war must be inwardly clean. His passion for justice must not be tainted by hidden uncleanness. As long as pacifists are in the minority, let them begin with a steady fight against all that is evil in themselves.”

All that is evil in themselves. So perhaps there are some shared anthropological assumptions between Niebuhr and Day. Because Dorothy Day and Father Stratmann, whom she quotes, admit that human nature is flawed, broken, wounded. Day encourages her readers to strive for the inner beauty of integrity and the outer witness of courage and hope in the face of difficulty.

Of course, it is impossible for me to know how either my grandfather or Dorothy Day would respond to the crisis in Syria. Perhaps both would be pleased with the potential for avoiding conflict that has surfaced recently. I’m pretty sure that my grandfather would be skeptical of Lavrov’s/Putin’s motives, voicing concern that Putin and the allies of Assad are engaged in delay tactics, not legitimate negotiations. Mr. Obama believes that it was the very real threat of strikes that even made this possible, something that Dorothy Day would not support, since she would not resort to threats of attack at all. The life and legacy of Dorothy Day is as powerful for me as that of my grandfather. Both draw on different assumptions about the world, privilege different parts of the Bible, and come to different conclusions about particular conflicts. But both lived faithful lives, trying to discern God’s will in the midst of the suffering they witnessed and endured. Maybe their conversation continues now in heaven.

As for me, my discernment continues. In general, I have found the just war perspective and just peacemaking perspective, as articulated by Mark Allman and others (see chapters four and five of WWJK?), to be a persuasive realistic approach to the complexities of modern warfare. This position says that sometimes conflict is justified, but only when certain criteria are met, and always for the ultimate end of peace. Tonight, Chris Matthews of MSNBC named some of my fears and hopes when he claimed (this is my transcription, not an official one):

[President Obama] said it would be moderate effort and moderate risk. Well, not to the people we’re bombing. They say it is not an act of war, but to the people we’re bombing it would be an act of war. And for days thereafter the pictures of every international television and on social media would be pictures of people in hospitals. And the American people would have killed so many hundreds of people. And the pictures of us as somehow the humanitarian country that cared about breaches in international norms would not sell…. Killing does not make the killing worse if you are killing those people. It doesn’t work that way. What works is international norms. And I think we have to go back and see/ I want to see us fighting every day in the UN. Every day Samantha Power is there, raising our voices. We’re against chemical weapons… We would be the great guys… We should become the champions of fighting weapons of mass destruction…

It is this hybrid approach between realism [what would the real outcomes of strikes on Syria be?] and idealism [let’s involve the UN and become the champions of fighting weapons of mass destruction!] that makes the most sense to me right now. It is not an argument to get involved or to avoid involvement simply out of strategic self-interest. But if we intervene, will we bring peace? Will our military involvement secure justice for the oppressed, security for the region? My discernment continues.

What do you think, reader?

You ask several times in this piece, now some three years ago, what would Dorothy Day have to say. I don’t think her basic answer would be any different from what she had to say about any of the wars that she experienced. It really came down to her most repeated reference to Mathew 24:45. She would ofcourse been more explicit/detailed in her reasoning as she was about those other wars. She analysed the particular war but she was adamant in repeating that you can’t ‘make peace by making war’. I do admit that coming across this throughout her writing has been quite a shock for me, such that it has made me pause. I can no longer find any wriggle-room.