Jeremiah 38:4-6, 8-10

Psalm 40

Hebrews 12:1-4

Luke 12:49-51

I’ve been reflecting recently on an article written by Jean Porter titled “The Subversion of Virtue: Acquired and Infused Virtues in the Summa Theologiae.” Her basic argument is that in drawing upon classical pagan sources, particularly Aristotle, for his description of the virtues within the Christian moral life required him to both affirm and to subvert that classical tradition, in order to reconcile it with a distinctively Christian and theological description of the moral life. Since her argument has been on my mind recently, I see a similar kind of subversion of expectations at work in each of these readings.

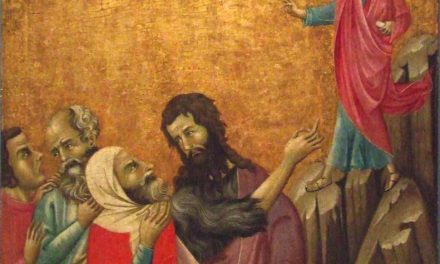

For example, the prophet Jeremiah suffered no shortage of tribulations for his prophetic call, and being thrown into a cistern is just one example of public ridicule that he had received for being God’s mouthpiece. We might surmise that as he sat int he mud at the bottom of the well he may have been thinking to himself (an Eeyeore-like tone), “well, what do you expect being a prophet?” And yet just when things looked dire, he was pulled from the mud by Ebed-melech and friends.

A similar subversion of expectations can be found in the letter to the Hebrews, where despite the public shame of crucifixion, Jesus overcame by “despising its shame,” and finding himself seated at God’s right hand. Finally, in Luke, the Messiah who is called Prince of Peace and who was to reconcile all things to himself (cf. Col 1:15) informs us that he will not bring peace but rather division.

Each of these readings seems to indicate something of the need to subvert common expectations in order to be able to enter the Kingdom of God. If we apply this to morality, this subversion indicates that somehow both of the following propositions are true: one must strive to do the best we can using our God-given faculties of reason, choice, and free will; and even that must be subverted in favor of a deeper way of living grounded in the kingdom.

This insight has long been recognized by some of the best thinkers in the Christian tradition. John Cassian, a monk who had studied with the great masters in the desert and brought much of their wisdom and insight into the Latin-speaking Western church, notes in his Conference XIV that one must achieve a basic level of virtue even to be able to read Scripture profitably. And yet he also indicates that it is through contact with the Word of God that one is more fully transformed into a life of Christian virtue.

Thus, Scripture extends even our natural capacities for virtue by showing them a higher plane at which they can function (ultimately these are brought under the highest virtue, which is love or caritas). In that way, Scripture provides the requisite subversion necessary to move from general morality to a distinctively Christian way of living, loving, and being in the world. Henri de Lubac calls this a “twofold” moral formation. In reading, reflecting upon, and praying with Scripture, our natural virtues are purified and also subverted and extended to reach both deeper and higher than we ever thought we could reach.

Though this sounds paradoxical, and indeed there is an element of paradox in the workings of the grace of Holy Spirit in the human heart, it is one that can only be fully understood when it is lived and experienced. Thus, when Scripture continually subverts our expectations as these readings do, we can only submit ourselves to this divine pedagogy and be awed at what may result.

I’m reminded of a few passages of Scripture:

“For if you love those who love you, what reward do you have? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? And if you greet only your brothers,h what more are you doing than others? Do not even the Gentiles do the same? You therefore must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” ~ Jesus (Matthew 5:46-48)

“If the world hates you, you know that it has hated Me before it hated you. “If you were of the world, the world would love its own; but because you are not of the world, but I chose you out of the world, because of this the world hates you.” ~ Jesus (John 15:18-19)

“Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.” ~ Saint Paul (Romans 12:2)

See: Christian Counter-Culture: The Message of the Sermon on the Mount – http://www.amazon.com/Christian-Counter-Culture-Message-Sermon-speaks/dp/087784660X