This post is part of a series on the Faith of Theologians. A full list of the previous responses by fellow colleagues can be found at the bottom of Dana Dillon’s post introducing and explaining the series.

This post is part of a series on the Faith of Theologians. A full list of the previous responses by fellow colleagues can be found at the bottom of Dana Dillon’s post introducing and explaining the series.

If you want to make God laugh, tell God your plans.

Two naive statements that I have made stand out in the development of my faith in relation to my vocation and career as a theologian. The first occurred when I was an undergraduate student studying in Rome. As a young theology major walking along the Tiber river I noted to a friend, “I hate moral theology. I can’t imagine why anyone would want to study it.”

The second occurred when I was studying for my Masters of Theological Studies while standing outside the library at the University of Notre Dame, talking to two friends fully committed to Thomas Aquinas’ approach to theology and I said, “I don’t know, I think maybe Aquinas is where it all went wrong.”

I am now employed as a moral theologian focusing primarily on the work of Thomas Aquinas – God is still laughing, and I am still shaking my head. How did this happen?

Something that I have noticed among my peers and among the students that I now teach is that there comes a time – usually right around the 18-22 year range of college – that one must decide whether or not faith matters. This looks different depending on what kind of family traditions one is steeped in. For cradle Catholics (like myself) this usually takes the form of an implicit or explicit question: Am I going to remain part of this church in which I grew up, or am I going to abandon it? I believe strongly that one’s view of faith, theology, and the church (or lack thereof) have a profound impact on how one answers this question. Hence, theology matters.

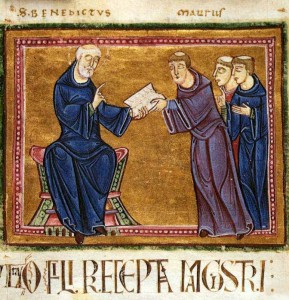

For me, I was lucky to be surrounded by a community of friends and Benedictines when I began asking these questions, and the simple, prayerful, contemplative approach to the Christian life and to theology in the Benedictine tradition struck a deep cord within me. That cord has kept me tethered to the Catholic Church, both when I appreciate its beauty and when I am confronted by its flaws and frustrations. (It also led me explore the monastic life, and eventually to commit to being an oblate of St. Benedict through St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, MN.)

My initial interests in theology were inspired by a love of the mystical and contemplative aspects of the Christian tradition, and a monk-friend-mentor of mine introduced me to centering prayer and lectio divina (as well as other forms of meditation and contemplation, especially in the work of the Vietnamese Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh). During my senior year of college I took a class on theology and social justice, and I was introduced to and fell in love with the tradition of Catholic social thought. This bore fruit in a year of community living and service after college with the Catholic Charities Volunteer Corps in St. Paul, MN.

During this year of service I continued to develop a regular practice of contemplative prayer, which became like the roots of a tree, keeping me grounded and (relatively) sane, while my work with Catholic Charities showed me a way to stretch out the branches of my faith into the fruits of action in the world. As I transitioned into that quasi-adult phase of academic life known as “graduate school,” I was slowly introduced to a broader perspective on the ways in which contemplation and action are linked together, especially in the work of Thomas Aquinas. I am particularly indebted to my classes on the theology of Thomas Aquinas with Jean Porter and Joseph Wawrykow, and I still remain inspired by the works of Servais Pinckaers, O.P., and Jean Pierre-Torrell, O.P., both of whom read Aquinas with academic rigor while also recognizing him as a master of the practical and spiritual life – that is, a person of deep faith.

I’ve also learned from Aquinas that contemplation is a spiritual practice that is linked to both the intellectual life (the cultivation of wisdom) and the world of action (the cultivation of virtue). Asking questions that take one further into the comprehension of the truth is central to the contemplative life; and living out that truth is part of faithful witness to the gospel. That is why I believe that “practical wisdom” (or the virtue prudence) is the heart of the moral life, the habit or skill that links together asking questions, discovering truth, and concrete action. Thus, my faith, as it is has been applied within my work as a theologian, has been strengthened by trust that asking questions and seeking answers can lead one closer to the source of truth – that is, to God – particularly when a sharpened, inquiring mind is open to and guided by the direction of the Holy Spirit.

Underneath this contemplative approach to moral theology lies a foundational belief – also confirmed in faith – that God has so created the world in an orderly fashion that asking questions about the nature of reality when done with honesty, integrity, and rigor always reflects a ray of God’s truth, and has the potential to lead back to God as Creator and Source. This is another way of stating that all philosophy begins in wonder. What this means practically for me is that in exploring contemplative prayer I have learned a great deal about meditation and contemplative practices from other traditions, in particular from Buddhist meditators and from the yoga tradition. I’m quite leery of two extreme approaches to such learning from other traditions. The first is an approach to inter-religious practice which follows a more intellectually lazy path of, “well, it all points to the same thing anyways.” The second extreme sees any engagement in practices outside of the Christian tradition (however one chooses to define that boundary) as dangerously leading away from God. Somewhere in the middle – and I am not really able yet to fully articulate where this space is – I cannot deny that my own practice of contemplative prayer, and thus my faith, has been deeply enriched by learning to quiet my mind from Buddhists and from learning to engage my entire body-spirit-mind in moving, flowing prayer from yogis.

Thus, I find that there are certain elements of my faith that remain like a solid foundation and other elements that continue to develop in new and unexpected ways. Sometimes these developments are a deepening of what was already there (e.g., learning certain skills from Buddhists and yogis that help me go deeper toward God in centering prayer and lectio), and sometimes they lead in exciting new directions. This, it strikes me, is all a part of living a life of the mind as an academic who remains rooted in faith. I cannot help but wonder which statements I have made recently that God is laughing about and is getting ready to guide me in new directions once again…

Trackbacks/Pingbacks