The readings for this Sunday may be found on the USCCB website:

- Acts 2:1-11

- Psalm 104:1, 29-31, 34

- 1 Corinthians 12:3-7,12-13

- Sequence: Veni, Sancte Spiritus

- John 20:19-23

Aristotle famously claimed that all humans have by nature a desire to know. This desire is built into our very bodies, in the delight we take in receiving new information through our senses. It characterizes most of all our distinctive mode of cognition and reasoning. Our minds hunger for knowledge just as our bodies hunger for food, but even when we are hungry we want to know what we are eating. This desire to know colors all our natural impulses, particularly our craving for social interaction. We speak of the development of social relationships as “getting to know someone.” We form such relationships by initiating and maintaining conversations in which we exchange information about ourselves and the world. A central feature of this natural desire to know, it seems to me, is the presumption that there is always something more, something new to learn. We never grow tired of discovering new things about the world, about others, and about ourselves. Despite the frequent difficulty involved in learning, and the real risk that what we discover may not always be welcome, we nevertheless extend ourselves outward to gain more and more knowledge. It is simply how we are made. As Bernard Lonergan put it, we have an “unrestricted desire to know.”

Perhaps this innate desire explains why we grow tired with dull routines and cliches, whose capacity to introduce us to something new appears exhausted, like chewing gum that has lost its flavor. This desire may also help explain the temptation many have to conspiracy theories or extremist demagogues: regardless of whether or not the information is true, at least it offers the illusion of something new. Yet it also explains the appeal of scientific discoveries and the thrill of traveling to distant lands. And it certainly lies behind the engine of modern capitalism, namely the imperative to advertise new products for purchase – products we need – at increasingly regular intervals. Thus part of our unlimited desire for knowledge is a desire for newness, a desire to learn things that elicit wonder and in fact feed our desire to know more. In this sense, our appetite for knowledge paradoxically finds greatest satisfaction in what increases this very appetite.

But of course, this appetite can go wrong. It can become disordered in seeking out things that seem to bring about our delight in newness but lead us away from our desire to know the truth. We are made to seek out the truth without end because we are made for God, and only what draws us into the inexhaustible newness of God will truly satisfy us in the end. The Christian moral tradition makes a distinction between the good and bad forms of this desire by calling the virtuous pursuit of true knowledge “inquisitiveness” and calling the vicious pursuit of novelty for novelty’s sake “curiosity.” Yet at the same time, it is important to acknowledge that our natural desire to know is not simply the compulsion to accrue accurate information, like a never-ending spreadsheet or encyclopedia. We are made to desire knowledge that surprises and awes us, but also helps us makes sense of our own existence. We long to know those things that make us excited and grateful to be living in a world so delightfully strange and immense, a world of endless mysteries for us to explore. Having faith that God loves us and that all truth proceeds and terminates in God, we can embrace new things with joy and hope, knowing that they all lead back somehow to the ultimate “object” of knowledge for which we were made.

Throughout the Bible, it is God’s Spirit that brings about true newness in the world. From the creation stories in Genesis to the parting of the sea in Exodus to the commissioning of the prophets, at every moment where God is breaking into the world to do something truly new, the marks of His Spirit are there. His wind/breath hovers over the waters, brings Adam to life, blows across the sea, enfleshes the dried bones of Israel. It makes sense, then, that it is the Holy Spirit who comes upon Mary so that she conceives the Incarnate Word in her body, and that it is the Holy Spirit who descends upon Jesus at His baptism, announcing the inbreaking of God’s Kingdom. The Holy Spirit reveals himself at work at every pivotal moment in salvation history. So what exactly is the Holy Spirit doing at Pentecost? What sort of newness comes into the world when the Holy Spirit descends upon the disciples?

The first point to note about Luke’s relatively brief account of Pentecost in Acts is that the disciples were gathered together, waiting in Jerusalem in obedience to what the Lord told them before he ascended into heaven. This period of waiting is the “flip side” of the human experience of authentic newness. We often have to wait for the newness we crave; we have to prepare ourselves to receive it and then patiently anticipate its coming at a time we do not know. One of the chief marks of curiositas is the illusion that we can uncover new delights at will, that we are more or less in control of our pursuit of knowledge. Yet experience tells us that the things that elicit the most wonder and give us the most delight are those things we never could have anticipated beforehand. Just as the best gifts are the ones we were not expecting, true newness manifests itself in a purely gratuitous way. True newness is a true gift, not an acquisition or a trophy of our own ingenuity. C.S. Lewis once compared prayer to digging a garden: you dig the furrows and plant the seeds, and then wait for the rains to come. The true fruit of the endeavor depends upon factors out of one’s control; the new life emerges only while one is waiting patiently for it to appear.

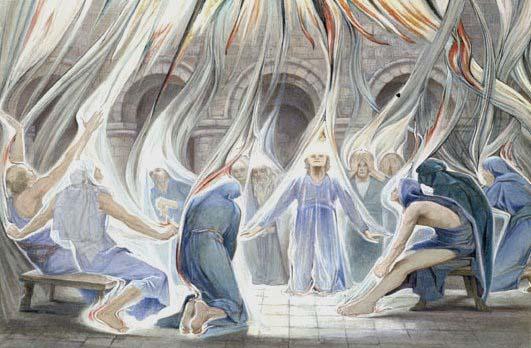

The second point to notice in the Pentcost account is that the Holy Spirit “filled the entire house” in which the disciples were gathered. Depictions of Pentecost often emphasize the physical description of the event: the noise like a blowing wind, the tongues as of flame appearing above their heads. Regardless of how literally we are to take such descriptions, the effect of the event is clear: “they were all filled with the Holy Spirit.” That word “filled” is perhaps the most important word in the reading. The disciples encountered the risen Lord for forty days, and according to John they even received the Holy Spirit when the Lord breathed upon them. The hearts of the disciples on the way to Emmaus burned when they listened to Jesus, and after recognizing him they became convinced of the resurrection and joyfully proclaimed it to others. Jesus’ reconciliation with Peter at Galilee offers closure and presumably gave Peter a new sense of resolution for the task ahead. But nowhere do find in these post-resurrection accounts the categorical statement that the disciples “were filled,” that they were fully satisfied or fully transformed by the joy and power of the new creation Jesus inaugurated.

This fullness gives the disciples the power to speak, to communicate clearly with those whose language and culture they do not share. It is the reversal of Babel, yes, but more importantly it is the beginning of a new community that integrates differences of background, status, race, sex, and nationality into a new corporate identity but without erasing or assimilating those differences. Luke takes pains to mention the places from which all those gathered in Jerusalem came. Why? Something new and greater has come into the world that offers a source a unity amidst difference, a new basis for integration and intimacy that transcends geography and ethnicity. These various identities do not simply dissolve, which is why Luke mentions the speaking of different tongues, and that each person understood the proclaimed message in their own language. That itself is a mark of authentic, God-ordained newness: the new does not abolish the old but heightens it as it draws it up into something greater. As the disciples draw in these new people into Christ’s body, they become more, not less themselves. Likewise, as we take on Christ’s identity in baptism, our own identity becomes more distinct, more individual and incommunicable. As St. John Paul II was so fond of recalling, only in the mystery of Christ does the mystery of our own identity become clear (Gaudium et Spes 22).

The “new thing” Pentecost brings about is the capacity to be filled with the Holy Spirit so as to receive the very life of God within us. This new life takes on a Christoform shape; the Holy Spirit allows us to live out the life of Christ in our own time and place, through our own unique, irreplaceable existence. In the gospel reading, Jesus himself breathes the Holy Spirit into the disciples; it is his breath, his life that enters them and gives them the power to do in their lives something utterly new in the world. Let us open ourselves up more fully to the new possibilities made possible by this historical “singularity,” which can nevertheless occur again and again both in the life of the Church and in our own lives. For it is only the Holy Spirit who can truly fulfill our natural desire to know by leading us, no doubt through strange and unpredictable paths, to the eternal vision of the One in whom all truth dwells, the One who is ever ancient and ever new.