Sally Yates and Elizabeth Warren have been in the news a lot lately as examples of tough women speaking up in difficult times. In both cases, we’ve seen the contested nature of women’s speech, an issue that Catholic women know all too well.

The Christian tradition has had its fair share of censure of women’s speech. Two often cited biblical texts have provided proof that it is ‘unnatural’ for women to take on public speaking roles:

According to the rule observed in all the assemblies of believers, women should keep silent in such gatherings. They may not speak. Rather, as the law states, submissiveness is indicated for them. If they want to learn anything, they should ask their husbands at home. It is a disgrace when a woman speaks in the assembly (1 Cor 14:34-35).

A woman must learn in silence and be completely submissive. I do not permit a woman to act as teacher, or in any way to have authority over a man; she must be quiet. For Adam was created first, Eve afterward; moreover, it was not Adam who was deceived but the woman. It was she who was led astray and fell into sin. She will be saved through childbearing, provided she continues in faith and love and holiness—her chastity being taken for granted (1 Tim 2:11-15).

Even today, official church practices restrict women’s opportunities to preach in the Catholic church. Women can earn doctoral degrees in theology and can teach in Catholic schools and colleges, but are restricted from preaching roles in most liturgical contexts.

Our tradition has a complicated history with regard to women’s stories. Mary Magdalene is celebrated as “apostle to the apostles” even while women are told that only men can be “apostles.” Women and men are celebrated for their “equal dignity” yet women are told that gender difference is part of God’s design and therefore some leadership roles are not possible for women in the church.

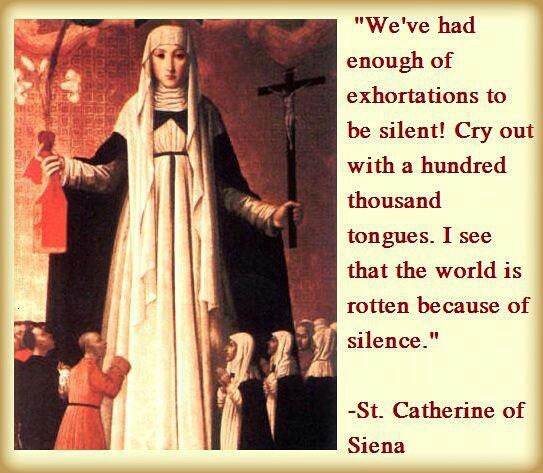

Yet some Catholic women are recovering the stories of female saints who seemed to challenge rigid gender-based stereotypes in their own days. One such saint is Catherine of Siena, a 14th century mystic and lay preacher known for her fierce loyalty to the church and for her willingness to speak boldly to clerical leaders in the hopes of challenging church corruption and fostering unity.

Mary Catherine Hilkert’s 2001 Madeleva lecture provides a brilliant recovery of St. Catherine’s story for a contemporary audience. There Hilkert explains that Catherine’s resolve was rooted in her baptismal vocation. From that starting point Catherine began a journey of discernment through which she felt called to speak in public and called to speak to church leaders in positions of authority. “Now I declare to you that it is God’s will for me to be here,” she wrote in a letter defending her apostolic activity (Hilkert, 30). “Everyone must be solicitous in his own trade; the trade which God has given us is this one.” (30).

Catherine’s letters provide examples of Christian freedom, for even as she was criticized for subverting expected gender roles and challenging leaders, she is unapologetic. Like women today who may wonder “What will people think of me if I speak up?”, Catherine tells her followers to follow their hearts. For example, she wrote to Daniele de Orvieto:

“If you see souls in danger and you can help them, don’t close your eyes… Work, then, my daughter, in the field you see God calling you to work in, and don’t trouble or weary your spirit over what is said to you but carry on courageously. Fear and serve God selflessly, and then don’t be bothered by what people say, except to have compassion for them.”

Hilkert notes that in reflecting on Mary Magdalene’s story, Catherine writes:

“If she had paid too much attention to herself, she would not have stayed [under the cross] with those people, Pilate’s soldiers, and she would not have gone and remained alone at the tomb. Her love kept her from thinking: ‘What impression with this make? Will they say bad things about me?’ She doesn’t think such things, but only how she can find and follow her Master. She knew the path [to holiness] so well that she has become our spiritual Maestra.” (32)

Within these narratives are some important lessons for Catholic women today. First, a life of prayer and ongoing discernment can strengthen one’s sense of vocation and empower one to act boldly when the time is right. It can be hard to know when to speak, especially when you are working within a corrupt institution (remember, Catherine was fighting corruption within the church during her time, but women today are active in lots of different kinds of institutional contexts- think of all the White House leaks!). Second, Catherine’s wisdom reminds us to speak up for the right reasons. Catherine’s advice was “Don’t worry about what others will say, only worry about doing the right thing.” Easier said than done, but such important wisdom in our own days. St. Catherine of Siena, pray for us.