In an earlier post, I looked in detail at the facts surrounding the Catholic publication The Pillar‘s exposé on the use of the gay hookup app Grindr by Msgr. Jeffrey Burrill, the former general secretary of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), based on location data derived from the app. I specifically examined how apps like Grindr collect and sell personal data, how The Pillar or their source might have obtained the data, what kind of data it is, and how Msgr. Burrill might have been personally identified from seemingly anonymous data. In particular, I speculated that The Pillar had obtained GPS location data that showed where Burrill had traveled, but without revealing information about his actual usage of the app, as alleged in the report, and that he had been personally identified by first discovering devices that had been located in the USCCB office or some similar location, and then linking those devices with specific individuals by tracing their location to a residence or other identifying location. This latter conclusion was later confirmed by The Pillar‘s journalists, JD Flynn and Ed Condon, in a podcast episode.

As Sam Sawyer, S.J. notes, ” The immediate responses to The Pillar’s story on Tuesday quickly bifurcated into reactions to the reported moral failures themselves and concerns about the methods used to report on them.” Like Sawyer, I think both of these moral considerations are important, and as I suggested in the earlier post, our attempts to hold Church leaders accountable for their moral failures will increasingly require is to think through carefully and clearly the moral issues related to digital privacy.

What is privacy?

We all have a desire to protect our privacy, but the concept of “privacy” is notoriously hard to define. The “private” is usually contrasted with the “public,” and so something that is private is that which has not been made public. We often think about the private and the public in spatial terms. We might say that we act differently “in the privacy of our own homes” than we do in public, for example at work or in other spaces deemed public. We can also speak of the “privacy of your person,” a sort of privacy that attaches to our bodies. This means, for example, that people cannot touch us without our consent or search our bodies for items we might possess. But this spatial understanding of privacy is not absolute. For example, the public may have a legitimate interest in knowing what goes on in our homes, with the most extreme examples being domestic violence or other crimes committed in our houses or apartments.

Privacy is sometimes linked to autonomy, meaning the right to decide for oneself what to think or to do without the scrutiny or regulation of others. This is how the “right to privacy” is often defined in the context of United States law, for example in the 1965 Supreme Court decision Griswold v. Connecticut protecting the right to buy birth control and the 1973 decision Roe v. Wade protecting the right to an abortion. But this definition of privacy is likewise problematic because it does not specify which sorts of actions one has autonomy over, or in other words which actions are public and which are private; for example, many Christians would deny that abortion is a private act precisely because it involves taking a human life. An exclusive focus on autonomy likewise ignores the essentially relational nature of being human and the role of responsibility in decision-making.

Elsewhere I have called for a more relational understanding of privacy drawn from the Christian theological tradition and centered around the communication of truth:

A better starting point for grasping the right to privacy is the traditional Christian understanding of communication. The purpose of communication, in this view, is to share the truth with another. The Christian tradition, however, recognizes that certain truths can be justly or appropriately shared with some people but not with others. Therefore, communication is a relational activity whose justice is dependent on the particular type of relationship involved and on whether the sharing promotes what is truly good. For example, the prohibition against lying does not mean that one must always reveal the truth when asked; one can withhold the truth if the questioner does not have a right to it. Similarly, gossip is wrong because it takes information that was given in confidence (or obtained without permission) and shares it with others who do not have a right to it. This same principle is applied in situations where professionals must exercise confidentiality about the intimate details of people’s lives: the priest’s seal of confession, the attorney-client privilege, and doctor-patient confidentiality.

We have an innate desire to know the truth because our deepest longing is to know and love God, who is the Truth. It is this love for truth that drives the human desire to know and explore the world around us. It is also out of love for the truth that we have a responsibility to communicate the truth, avoiding lies and gossip. Both individually and organizationally, we have a responsibility to be transparent, to share the truth with those who have a right to know it, whether it is our spouse, business customers, or the public at large.

Even though our innate desire for the truth is infinite and can only be fulfilled by God, there are limitations on the knowledge we ought to pursue that result from our fallen nature. In his discussion of the vice of curiosity, the medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas provides a number of examples of when our desire for knowledge can become sinful, for example, when this desire distracts us from some other responsibility, when it leads us to associate with someone who may be a bad influence (Aquinas gives the example of demons!), when our knowledge leads us to pride, and when we take an inordinate interest in other people’s actions to harm them in some way, among others (ST II-II, q. 167, aa. 1-2). We also have a duty to protect any sensitive knowledge that has been entrusted to us from those who have no right to it. I believe these principles can help guide us as we think through the privacy issues arising from digital technology:

Although they were developed to address personal relationships and communications, these ethical concepts can be used to address the institutional questions of data collection and privacy that we face in the twenty-first century. One of the defining characteristics of modernity is the replacement of social relationships that had previously been based on personal trust with impersonal relationships founded on a more institutional form of trust. It is this institutional trust that necessitates the collection of personal data. In this context, the right to privacy refers to the expectation that personal information shared with an institution will be kept in confidence: it will not be shared with others and will be protected from intruders who do not have a right to it. Privacy must be balanced by transparency, the moral duty to share information to which others have a right.

These questions of privacy and transparency are at the heart of the situation raised by The Pillar‘s exposé, both at the personal and institutional level, and regarding both the Church and the companies that handle our data.

Being transparent about Msgr. Burrill’s actions

In their report, The Pillar cites the moral theologian Thomas Berg’s assessment that Burrill’s use of the Grindr app is a violation of a priest’s obligation to continence and chastity. Berg also notes the problem of a priest living a “double life”: “That almost always impacts the lives of other people around them because deception breeds deception breeds deception.” In his analysis of the situation, Zac Davis echoes this view, saying, “Regardless of how it became public …, it is important to acknowledge that it is a bad thing if the highest-ranking priest in the U.S. church is regularly breaking his promise of celibacy.”

Davis goes on to identify a further problem with Burrill’s conduct:

Monsignor Burrill, while not a household name, is not an average Catholic, or even an average cleric. As general secretary of the U.S.C.C.B., he helped run a prominent body representing the church in the United States and maintained significant influence over church policies and statements—including those dealing with reporting on sexual misconduct—that have an impact on the entire church. If someone charged with helping the church become more transparent, a task for which Monsignor Burrill was in part tapped after the sexual abuse crisis again came to the forefront in 2018, is leading a life that is not transparent, it hurts the church’s credibility and ability to live out its mission. No Christian should take delight in how this news came to light, but neither should anyone suggest it is not important or dismiss it with claims that we all sin, after all.

It is hard to see how Burrill could have remained in his position while maintaining any moral authority once the facts of his conduct became known. As Davis cautions, however, the conclusions drawn about Burrill’s conduct are inferences drawn from data, and as I pointed out in my earlier post, the data does not seem to tell us as much about Burrill’s use of the Grindr app as The Pillar‘s report suggests. Still, it seems safe to conclude that he engaged in some kind of sexual misconduct, and his decision to resign may have come after a more detailed discussion of his conduct with officials at the USCCB.

Although Msgr. Burrill’s conduct was scandalous and he deserved to be held accountable for it, there remain questions about how this information came to be public. As Christians we are called to be transparent about our sins, acknowledging them and confessing them to God and the Church. The Church has a responsibility to hold its members accountable for their sins, perhaps particularly the Church’s leaders. But this is not the same thing as an absolute right to know the sins of Church members or to invade their private lives in search of sin. As Jesus points out (Mt. 13:24-43), the desire to root out sin can lead to its own types of sins. A just balance between transparency and privacy must be found, a task particularly important in our digital age. In Msgr. Burrill’s case, this will require examining the ethical questions concerning how his data was collected, how it was sold and ultimately provided to The Pillar, and how it was publicized by The Pillar. One might argue that had Msgr. Burrill simply not used Grindr, which he should not have done, then his private data would not have been collected or shared, and none of these other ethical questions would matter. At one level this is true, but it ignores how Msgr. Burrill’s unfortunate choices were entangled in a web that has ensnared us all, whether we use Grindr or not, and that raise ethical questions that demand an answer from us.

Grindr’s Collection and Distribution of Personal Data

A report by Mozilla on the security of a number of dating apps says “Historically, Gindr has had a horrible track record on privacy, including coming under fire for its data breaches and sharing user data to advertisers without user consent.” As I explained in my previous post, Grindr collects the data users enter into their profiles as well as GPS location data from their phones. This data is then sold to a number of data brokers, who link this data to other data that has been collected on the user in any number of other ways (other apps, web searches, etc.). The data is linked using personally-identifying information like an IP address or mobile advertising ID. This data is then used to generate targeted ads that are sent back to the user’s Grindr app. The data is also sold to countless third parties, mainly for purposes of advertising or market research. These practices are arguably a violation of users’ privacy (earlier this year, Norway fined Grindr $11.7 million dollars over the practice, which it argued violated the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), discussed below). Grindr has also been indiscreet about what data it shares. In 2018 it was discovered that Grindr had shared users’ HIV status with third party vendors, a practice it now claims it has stopped.

Grindr has faced other problems with users’ location data. Grindr does not broadcast users’ location to other users. Instead, it simply shows a user others who are nearby and the distance between the users. In 2014, it was discovered that using the distances between multiple users, one could mathematically “triangulate” a person’s location. In countries where homosexuality is criminalized or taboo, Grindr has allowed gay men to connect with one another with a certain level of privacy. In Egypt, however, government officials learned how to triangulate users’ locations and used this technique to identify and arrest users. Grindr has since stopped collecting location data in countries where homosexuality is criminalized and made distance sharing optional.

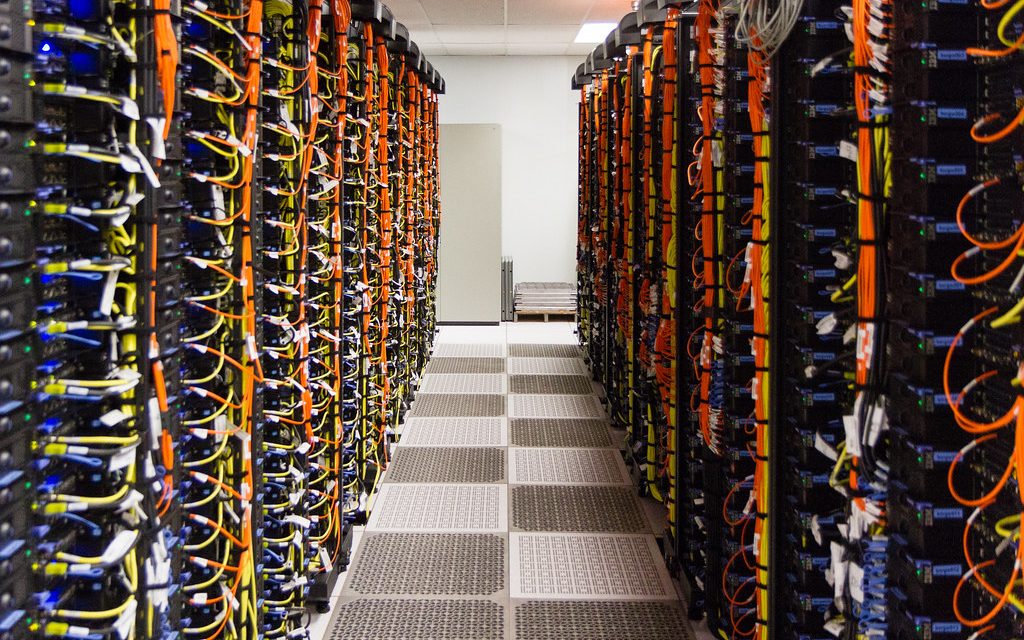

The Problem of Consent

Of course, Grindr is not the only app to collect users’ personal information. Most apps collect data of some form or another, and many of them sell this data to brokers in much the same way as Grindr. It is not just apps, however. The web sites we visit on the internet collect data about our internet usage, including our browser and search histories, our online purchases, and the ads and articles we click on, and they in turn sell this data. Our internet service providers do the same. “Smart” products like robotic vacuum cleaners, personal assistants like Amazon’s Alexa, and health devices like Fitbit collect and in some cases sell data on the layout of our houses, our health, and even our conversations. Our cars likewise collect and sell information on our location and driving habits. Supermarkets collect and share data on our purchases. All of this data ends up in the hands of data brokers.

The psychologist and author Shoshanna Zuboff calls this new reality “surveillance capitalism.” In her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, she argues:

We are no longer the subjects of value realization. Nor are we, as some have insisted, the “product” of [surveillance capitalists’] sales. Instead, we are the objects from which raw materials are extracted and expropriated for [surveillance capitalists’] prediction factories. Predictions about our behavior are [the surveillance capitalists’] products, and they are sold to its actual customers but not to us. We are the means to others’ ends. (p. 94)

Her last phrase is evocative; it suggests that it is no longer the products of our work, what Pope John Paul II called “the objective sense” of work in his 1981 encyclical Laborem Exercens (no. 5), that are commodified, but something of our subjective experience, generating a kind of alienation from ourselves, a kind of de-humanization. In the past, we may have shared this sensitive information with trusted counselors in specific contexts where confidentiality is expected: a doctor, a financial advisor, a priest. Now it is shared on an open market where we have no control over who sees it or how it is used.

But don’t we all consent to handing over this information? Indeed, one refrain in response to The Pillar‘s report has been that Msgr. Burrill had no expectation of privacy concerning information he himself made public. We can approach this issue in two ways. Most Millennials and Zoomers have grown up being warned to be careful that an embarrassing photo posted on Facebook or Instagram could be seen by a potential employer, for example. But that is not a good analogy for Msgr. Burrill’s situation. Although of course he recklessly put himself at risk of being “outed” by using the app, it was not public data available to Grindr’s users that was used by The Pillar. As I have already noted, Grindr does not post users’ particular location, it only shows users those other users who are nearby (and in fact the ability to calculate a user’s location using information about their distance was considered a grave privacy breach!). In addition, a Grindr user can create an anonymous username, so using Grindr does not entail making your personal location or personal identity public. The issue in this case, and with surveillance capitalism generally, is not the information you publicly post about yourself, but the information the apps collect as we use them, what Zuboff refers to as the “second text” or “shadow text” behind the “first text” of the app’s interface.

Even so, we still consent to the collection, and even the selling, of our data when we agree to the terms of service and privacy policies of the apps, web sites, and products we use every day. Of course, sometimes apps are caught collecting data without our consent, but how can we object in those cases where our data is being used in ways we ourselves agreed to? There is a certain irony in the fact that Msgr. Burrill was caught using an app through which consenting adults can meet and engage in consensual sexual activity, and yet the most vocal defenders of of sharing and publicizing his data do so on the grounds that he consented (Flynn and Condon themselves make this argument in a podcast episode released after the report’s publication). My point is not that Msgr. Burrill’s behavior was acceptable because it was consensual; rather, it is the opposite: consent, although necessary, is never sufficient to render an agreement ethically virtuous, a principle that has implications in sexual, medical, and commercial contexts, among others. For example, in his 1961 encyclical Mater et Magistra, Pope John XXIII writes that a labor contract “must be determined by the laws of justice and equity” or risk being ” a clear violation of justice, even supposing the contract of work to have been freely entered into by both parties” (no. 18). The same principles of justice and equity apply to terms of service agreements.

These terms of service agreements, sometimes referred to as “clickwrap” or “clickthrough” agreements, are a type of “contract of adhesion,” that is, a contract in which there is an unequal bargaining position between the parties and the stronger party can impose the terms of the agreement on a “take it or leave it” basis. These contracts are legal (they include home mortgages and car purchases, for example), but they can be scrutinized and even voided if the unequal bargaining power results in provisions that are unreasonable or unfair. For example, a U.S. federal judge in 2007 ruled that a clause requiring all claims be submitted to arbitration in the terms of service for the virtual world Second Life were “unconscionable” and therefore void, despite the user’s consent, and likewise a Canadian court in 2017 ruled that Facebook’s requirement that legal actions against it be brought to court in California was unreasonable, despite the user’s consent. Given that access to the internet is in many ways a practical necessity today, and apps such as Facebook and Twitter are important public forums, there is certainly a powerful case that non-negotiable terms of service requiring us to sign away our privacy to participate in public life are unreasonable, and therefore unjust, expectations.

Clickwrap agreements also use ambiguous language to conceal what data will be collected or sold. For example, a user might be told that “no personally-identifying information will be sold to third parties.” But the agreement may not explain that “personally-identifying information” only refers to information such as your name, Social Security number, or email address. The user may be unaware that the app is still collecting data that could be used to personally identify them, such as their IP address or GPS location data, or that data brokers may be using a personal identifier like a mobile advertising ID to create a personal profile of them and that could be used to “de-anonymize” their information.

In addition, clickwrap agreements are written with the intent of discouraging users from reading them. A study conducted in 2008 found that it would take about 244 hours per person to read the terms of service for the web sites visited by the typical person in a year, or more than half the time the average person spent online at the time. Zuboff notes that time would be much longer today when factoring in our increased internet use compared to thirteen years ago and the widespread adoption of apps on smartphones. And this does not even factor in the sale of our data. An app’s terms of service agreement makes the user beholden to the privacy policies of the companies to whom it sells their data and puts the burden on the user to examine those policies, even without informing the user which companies may have their data. As I explained in my previous post, Grindr, for example, shares data with a number of data brokers, and then one of them, AppNexus, potentially sells that data to over 4,000 third parties, OpenX makes data available to 34,000 advertisers, and so on. Under these conditions, the implication that users have “consented” to the privacy policies of all of these parties is patently absurd.

As I briefly noted in my previous post, one problem with surveillance capitalism is that data brokers may sell our personal data to companies with little scruples about passing that data to individuals who have no right to it or who plan to use the data for nefarious purposes. Journalists have already tracked cases where personal data, including extensive location data, has been sold to bounty hunters, debt collectors, and stalkers. It is not difficult to imagine how this information could fall into the hands of domestic abusers, pedophiles, blackmailers, and doxxers, among others.

Surveillance Capitalism is a Structure of Sin

In his Reconciliatio et Paenitentia (no. 16) and Sollicitudo Rei Socialis (no. 36), Pope John Paul described the phenomenon of social sin or structures of sin: complex structures built up and consolidated by personal sins but that operate anonymously on a vast scale, damaging human development, influencing people’s behavior, and encouraging further sin. Given the conditions I have outlined above, I think it is fair to say that “surveillance capitalism” as it is currently practiced represents a structure of sin. Those who participate in the trade of people’s personal data, particularly in situations where individuals’ consent is abused, or where there are few safeguards against the “de-anonymization” of individuals’ data or the sale of data to unauthorized buyers, are engaged in material, if not formal, cooperation with evil, the gravity of which would be dependent on their role and context. If someone has been entrusted with private data for legitimate purposes, knowingly or carelessly selling or offering such data to a person or entity who wishes to use it for purposes contrary to what the original source of the data had a reasonable expectation to have consented to is a sin, possibly a grave one, even if it is legal (and in at least some cases it may not be legal, if the sale violates terms regarding the use of the data or sale to authorized buyers).

Just to make my point clear, I am not saying that the sale of personal data and its use for targeted advertising is per se evil. Rather, the practices involved need to be regulated to bring greater justice to the process and to prevent data from falling into the wrong hands. For example, the European Union’s GDPR has several provisions that make the sale of personal data more just:

- First, companies must write their privacy policies in clear, easy to understand language.

- Second, companies cannot sell users’ personal data unless the user opts in and cannot withhold services if the user opts out; users can also withdraw their consent at any time. This eliminates the “take it or leave it” power imbalance in the terms of service.

- Third, companies that sell users’ data are responsible for ensuring that buyers are using the data responsibly. This takes much of the onus off of the user.

- Lastly, users have the right to know when their data has been sold, to access the information that was sold, and to correct it if there are errors.

By promoting greater transparency about how individuals’ data is used, the GDPR protects their privacy while also recognizing the legitimacy of collecting and selling data, establishing a more just outcome than the present situation in the United States.

Journalistic Ethics and Detraction

I have gone on for too long, but I must return to the question of whether the dissemination and publication of Msgr. Burrill’s data was ethical. In the podcast episode discussing their report, Flynn and Condon insist that their source had obtained the data legally, and that they obtained it from the source legally. This is difficult to assess without knowing who the source is and how they obtained the data, but given the lack of digital privacy regulation, it is likely true. Nevertheless, even if providing the data to the journalists was consistent with the letter of the law, it was inconsistent with the spirit. As I speculated in my previous post, and as The Pillar has since confirmed, the source obtained Msgr. Burrill’s data as part of a massive bundle of anonymous data intended for commercial purposes. It is hard to imagine a situation in which the source was authorized to de-anonymize the data of particular people included in the bundle to trace their individual behaviors, or to show others how to do so. The notion that Msgr. Burrill, by consenting to Grindr’s privacy policy which claims that users’ data will be shared with third parties either for analytics purposes “without identifying individual visitors” or for advertising purposes, had therefore consented to having his data de-anonymized and to being “outed” is “unconscionable.” We deserve more information on the source, how they obtained the data, and their motives, although Flynn and Condon are right that it was not their responsibility as journalists to seek out that information before reporting, as long as they could confirm the reliability of the data itself.

Even though I find the distribution of the data to The Pillar deeply unethical, the question of whether its use by The Pillar was unethical is more complex. As they rightly explain in the podcast episode mentioned earlier, it is not unusual for journalists to receive and use information their sources obtained through morally questionable or even illegal methods. For example, it was legitimate for journalists to publish and report on the DNC and Clinton campaign emails during the 2016 presidential campaign, even though the hacking and leaking of those emails was unethical and illegal.

After The Pillar journalists obtained the data, they themselves analyzed it and “de-anonymized” Msgr. Burrill’s data. At the blog Where Peter Is, Mike Lewis argues that the fact that The Pillar‘s decision to publish information derived from de-anonymized data is unprecedented (a fact confirmed by experienced tech reporters) demonstrates that they had violated journalistic ethics by doing so. Flynn and Condon point to reporting from earlier this year by the New York Times that identified January 6 insurrectionists using GPS location data from their phones as a precedent for their work, but the Times did not de-anonymize individuals’ data without their consent. The purpose of the Times‘ reporting was not to expose the identity of the insurrectionists, but to expose the risks such data poses to our privacy. As a former Times reporter who worked on the story, Charlie Werzel, said to the Washington Post, ” This [i.e., The Pillar‘s report] was the nightmare scenario that we were talking about to some degree. . . . To see it happen is just confirmation of just how dangerous this type of information is. . . . Despite the fact that I don’t think there are any ethical similarities with what we did and this, it obviously makes me feel terrible that our work was used as a justification in this.”

That being said, I don’t think the problem with The Pillar‘s reporting was the fact that they received the data from their source or that they de-anonymized Burrill’s data, but that they used this circumstantial evidence to make accusations regarding Burrill’s behavior without greater corroboration. As Dr. William J. Thorn, a professor emeritus of journalism and media studies at Marquette University, told the Catholic News Agency:

New data mining technology poses a plethora of privacy issues for investigative journalism, regarding both prominent individuals and ordinary citizens, for example, in areas like health and personal habits, which require some verifiable contextual evidence to reach a fact-based conclusion. But legal boundaries differ from moral constraints which require care for the impact of conclusions based on less than reliable abstract [data] which can destroy or seriously damage an individual’s reputation.

As I have already explained, The Pillar draws conclusions about Burrill’s behavior that are not justified by the data, at least as it has been presented, and this is a problem I think is magnified in their reporting on “hookup app” use in rectories and clerical residences in the Archdiocese of Newark, since they have not been able to personally identify app users or to make sure the users they have identified are actually priests and not housekeepers, parishioners, or other guests who may have frequented a rectory or clerical residence.

One last consideration on whether The Pillar had a duty to publicly report on their findings. Lewis accuses the journalists of the sin of detraction, which the Catechism of the Catholic Church describes in these terms: “Respect for the reputation of persons forbids every attitude and word likely to cause them unjust injury. He becomes guilty … of detraction who, without objectively valid reason, discloses another’s faults and failings to persons who did not know them.” He argues that once Burrill had resigned, there was no need to make the report public afterwards. If the purpose was to hold Burrill accountable, that had been accomplished. Lewis writes:

It seems that Flynn and Condon may imagine this being the first step in an attempt to bring the institution to its knees and into a new era of accountability. But how does any of that justify singling out and shaming a single middle-aged bureaucratic priest from Wisconsin who had already resigned from his job and whose ecclesial career was likely done? Once again, do the ends justify the means?

Two things stand out in the Catechism‘s definition of detraction. First, just because something is true doesn’t mean it should or must be shared with others. Second, information about another’s faults can be shared if there is an objectively valid reason and if there is no unjust injury to the person. What counts as an objectively valid reason or an unjust injury, however? In his Summa Theologiae, Aquinas argues that if the intent is to dishonor a person, then revealing their sins to others publicly (“reviling”) or secretly (“backbiting”) is sinful. If the intent is to correct the individual, or what today we might call “transparency,” revealing another’s faults might still become sinful if this is done without moderation or due consideration, or if it does not serve a “necessary good.” ( ST I-II, q. 72, aa. 1-2 and q. 73, aa. 1-2) Although helpful, this is just as vague as the Catechism‘s call for an “objectively valid reason.”

In the podcast episode, Flynn and Condon provide two reasons they believe justified the publication of the information:

- The “serial” nature of Burrill’s misconduct, suggesting a pattern of behavior rather than a single mistake that was later repented of;

- Burrill’s leadership position at the USCCB, including his role helping to coordinate the U.S. bishops’ response to the Church’s 2018 sexual abuse and coercion scandals.

As I explained in my previous post, however, the claim that Burrill engaged in “serial” misconduct is unsupported by the evidence, at least as reported. The GPS location data provided to The Pillar, although collected by the Grindr app, only shows places Burrill visited while being tracked by his phone and tells us very little about his actual behavior. As I also noted, however, the facts that he had downloaded Grindr and visited a “gay bathhouse” in Las Vegas suggest some kind of misconduct, but we are short on details. So it is noteworthy that one of the reasons provided by The Pillar for publishing the story (rather than simply reporting the information to the USCCB, for example) is unsubstantiated.

Lewis also suggests that Burrill’s oversight role concerning clergy conduct is exaggerated. Even if true, Burrill is still in a position of responsibility, and especially in light of the ongoing abuse and coverup scandal, I think there should be a presumption in favor of transparency when it comes to misconduct by Church leaders. But the lack of corroborating evidence regarding Burrill’s actual conduct and its supposed “serial” nature reinforces the impression that this was an attempt to hurt his reputation rather than promote transparency. It is difficult to say whether the reporting was justified or not without more information. I am more concerned about the unanswered questions and lack of limiting principles regarding similar situations that arise in the future. We need further clarification about what sorts of misconduct merit public reporting, what merits reporting to a superior, and what should remain between an individual and their confessor. We also need to discuss if there are different levels of transparency and accountability for Church leaders, pastors, and lay people (aside from legal liability, of course, which should be the same for everyone). And lastly, we need to discuss how we can resist our culture’s temptations of detraction and shaming, instead promoting a culture of transparent acknowledgement of wrongdoing matched with penance and reconciliation.