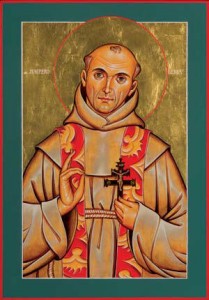

A few years ago I wrote a piece here on the blog about why we need a postcolonial hagiography. I explained then that Catholic social teaching and liberation theologies have helpfully developed away from a paternalistic narrative of the good white European who saves the bad/poor/savage dark-skinned native, and that contemporary discourse calls for solidarity and the promotion of a just social order that ends the domination of some countries by others. I said that our hagiography needed a similar updating. Now that Pope Francis has canonized the first Hispanic American saint, are we making progress? I think so.

While there was intense debate in the build up to the Canonization Mass for Junipero Serra, the pope’s interpretation of this man’s legacy highlighted the dignity of native peoples and the sacrifices of missionaries. First Pope Francis acknowledged the messiness of evangelization:

“Mission is never the fruit of a perfectly planned program or a well-organized manual. Mission is always the fruit of a life which knows what it is to be found and healed, encountered and forgiven. Mission is born of a constant experience of God’s merciful anointing. The Church, the holy People of God, treads the dust-laden paths of history, so often traversed by conflict, injustice and violence, in order to encounter her children, our brothers and sisters.”

While light on the details, the pope still acknowledged conflict, injustice, and violence as human realities. He praised Serra for the way he treated indigenous communities with respect, seeing God in the face of every person.

“Today we remember one of those witnesses who testified to the joy of the Gospel in these lands, Father Junípero Serra. He was the embodiment of “a Church which goes forth”, a Church which sets out to bring everywhere the reconciling tenderness of God. Junípero Serra left his native land and its way of life. He was excited about blazing trails, going forth to meet many people, learning and valuing their particular customs and ways of life. He learned how to bring to birth and nurture God’s life in the faces of everyone he met; he made them his brothers and sisters. Junípero sought to defend the dignity of the native community, to protect it from those who had mistreated and abused it. Mistreatment and wrongs which today still trouble us, especially because of the hurt which they cause in the lives of many people.”

Yes, the mistreatment of Native Americans should continue to bother us. Gregory Orfalea explains:

“Part of the current puzzlement and anger over the Serra canonization is motivated by an entirely justified revulsion over the historic crimes committed against the Indians. Until the past few decades, American culture was largely indifferent to those crimes, and portrayed the victims as savages….We must put away the caricatures of Hollywood, and come to terms with the real history—the near extermination—of Native Americans at the hands of white Americans. But if that is the case, I think an understanding of the real Serra is just as essential. The historical record tells us that Serra was neither the perfect man the pious long for nor the vicious conquistador others imagine him to have been.”

Orfalea notes that Pope Francis has already named Spanish colonialism a sin when he was in Bolivia in July:

“There was sin. There was sin, and in abundance, and for this we ask forgiveness. But…where there was sin, where there was abundant sin, grace abounded, through these men who defended the justice of the native peoples.”

In his address to the United States Congress today, Pope Francis continues this line of thinking:

“Tragically, the rights of those who were here long before us were not always respected. For those peoples and their nations, from the heart of American democracy, I wish to reaffirm my highest esteem and appreciation. Those first contacts were often turbulent and violent, but it is difficult to judge the past by the criteria of the present. Nonetheless, when the stranger in our midst appeals to us, we must not repeat the sins and errors of the past. We must resolve now to live as nobly and as justly as possible, as we educate new generations not to turn their back on our ‘neighbors’ and everything around us. Building a nation calls us to recognize that we must constantly relate to others, rejecting a mindset of hostility in order to adopt one of reciprocal subsidiarity.”

Here Pope Francis is warning us of the dangers of ethnocentrism and encouraging Catholics to adopt a decolonizing gaze. Such a task is not easy. But this pope has repeatedly focused on dialogue as the locus of evangelization. He names atrocities of the past as sins. This is a positive step forward. Today he also warned against the dangers of fundamentalism:

“Our world is increasingly a place of violent conflict, hatred, and brutal atrocities, committed even in the name of God and of religion. We know that no religion is immune from forms of individual delusion or ideological extremism.”

So too should Christians repent of the harm done to native peoples through missionary conquests. As he did in Evangelii Gaudium, so too in his homily at the Serra Canonization Mass, the pope encourages Catholics to have missionary zeal and to communicate to others that the source of their joy is God’s love. He explained the importance of listening and of inclusion.

Scholars of postcolonial theologies and intercultural dialogue have paved the way for a deeper understanding of what such a posture entails. As Orlando Espin has argued in his latest book, Idol & Grace, we need to move beyond “inculturation” which is associated with colonization and the acceptance of another’s truth. Espin explains:

“Instead of inculturation, we should perhaps speak of “inter-trans-culturation,” whereby another witnesses to me, in an open inter-discursive dialogue, what he or she understands and lives as truth, and I, within and from within my own cultural perspective, will contrast and perhaps assume that truth, because I have discovered it as truth within and from within my cultural horizon. And I in turn, upon my discovery of truth as it is possible within and from within my cultural perspective, witness to the other, again in an open interdiscursive dialogue, what I have come to understand and live as truth, inviting the other to question and grow in what that other person understands and lives as truth. Thus we move the process into an ever-deepening and continuing dialogue where truth is discovered and affirmed, over and over, through mutual witnessing, contrasting dialogue, and non-colonizing reflection.” (Idol & Grace, 63).

Note the differences between conquest and dialogue as noted here! Musimbi R. A. Kanyoro describes this task as “cultural hermeneutics,” saying that it “can open our eyes to possibilities that might move us to different commitments.” (“Cultural Hermeneutics: An African Contribution.” See also the work of Musa Dube and Kwok Pui-Lan for examples of feminist postcolonial theologies).

I firmly believe that we are making slow and steady progress in recognizing the harm of colonial conquest, decolonizing our theological categories, and reaffirming the necessity of mutual understanding and mutual respect in our approach to mission for the twenty-first century. Our way forward must include honesty about harms of the past and present as well as motivation for having difficult dialogues around contested issues. The pope is right: too much violence is committed in the name of God and no religion is immune. We are all called to be peacemakers, and this requires intercultural understanding. Siempre adelante! Let us keep moving forward in this difficult but essential task of Christian discipleship.