I bought my daughter the New Picture Book of Saints (1962, reprinted in 1974, 1979, and 1988) at the Borders that is going out of business. I didn’t really look at it carefully until we got home. Unfortunately, all sales are final.

Why do I regret this purchase? After all, Fr. Lovasik writes in the book’s introduction:

I have prepared these life stories of the saints and these wonderful pictures in color to help you to know the saints better. They are your brothers and sisters in heaven. They want to help you get to heaven. Try to be like the saints in doing all you can to know, love, and serve God as they did, and in this way save your soul. Ask the saints to help you to practice virtue and to overcome sin.

Sounds okay so far, right?

Veneration of the saints is an important part of Catholic tradition. One of the ways we are formed as moral persons is that we learn about the stories of holy men and women who’ve gone before us in the faith. They model the Christian life, and can be role models for us.

The problem is that retrieval of the stories of saints involves us in the task of interpretation. We have to ask ourselves, what does Fr. Lovasik have in mind when he proposes that we “serve God as they did”? When Fr. Lovasik says that children should ask the saints to help them “practice virtue,” what virtues does he have in mind?

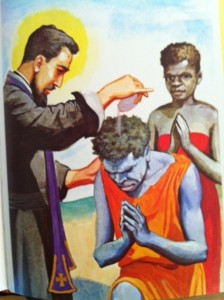

I find the interpretation of two saints in this book particularly troubling because they uncritically present the Church as consistent with colonial power. Unfortunately, some Catholics continue to engage in religious discourse that privileges Eurocentric theology and frames other voices as “other” and implicitly less traditional, less authentic, and less Catholic.

In the description of St. Peter Claver, the author explains that the saint was born in Spain but spent forty years in South America in solidarity with enslaved peoples. It is worth quoting the description in full:

He consecrated himself by vow to the salvation of those ignorant and miserable people, and he called himself “the slave of the slaves.” He was their apostle, father, physician, and friend. When news arrived of a slave ship coming into port, Peter would go on board at once and bring comfort to his dear slaves. He fed and clothed them, and nursed them with the greatest tenderness in their ugly diseases. It is said that he baptized forty thousand Negro slaves before he went to his reward in 1654 (85).

How will a child respond to the description of black slaves as “ignorant,” “miserable,” and faced with “ugly” diseases? I do not wish to challenge the assumption that Peter Claver was a holy man and a man of courage. But does this portrait tell enough of the story? Here we have a picture of a white European male who is holy and self-giving and is baptizing a poor ignorant slave.

Another Jesuit, Saint Isaac Jogues, is lauded for his missionary work in New France in the early 1600s:

He joined the Society of Jesus and was sent to New France, as Canada was then called. His joy was great as he stepped on shore in the New World. For years he had dreamed of leading the savage redskins to the feet of Christ. Father Jogues and his companions suffered great hardships and were always in danger of death. Whenever anything went wrong among the Indians, the “Blackrobes” were blamed. On an expedition to Quebec to supplies of medicine and food, Father Jogues and his companions were surrounded by a band of Iroquois, who were the most warlike of the Indian tribes. They were taken captive and were tortured without mercy for months. When the French government tried to secure his freedom, Father Jogues wrote: “I prefer to remain as a captive unless it be the will of God that I escape.” Later, he did escape and returned to France. But Father Jogues again returned to the Indians. One evening he was seized in the wigwam of an Iroquois chief. His head was crushed with a tomahawk and he was scalped (87).

Here again, the holy saint seems to represent the “civilized” European in contrast to the “savage” indigenous community. We whitewash the savagery of the colonial powers in this retelling of the heroic virtue of these saints.

I would argue that Catholics need to be much more sensitive in our retelling of our history and that we should be especially careful not to perpetuate colonial interpretations of Scripture and Tradition in devotional literature. Keeping our young children away from texts like these can be one step in the right direction. But helping older children to understand what is problematic about these texts is even more important.

Catholics should be much more engaged in postcolonial discourse. As Francisco Lozada explains in his description of postcolonialism in An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies:

Postcolonial theory represents a fluid approach that aims to de-ideologize “colonial” interpretations that universalize or totalize history, tradition, and/or what is considered “other” by dominant cultures, countries, and persons. In the 1980s, diasporic intellectuals from “third world” countries with a long history of political, economic, military, and cultural colonization by the United States and/or European countries began to focus on the intellectual consequences of colonization (1062).

Postcolonial approaches share some common ground with postmodern deconstructionist approaches in that there is a conscious shift to a perspectival and particular approach and an understanding of knowledge as always partial and limited. This challenge must be kept in mind when we think about the history of the Catholic Church and what is liberating or sinful within that tradition. Lozada explains that scholars in religious studies/theology need to “examine the colonial configurations of their own textual canons and interpretive traditions” (1063).

When we reconsider the complicity of the Catholic Church in the colonization of Latin America, we will recognize saints as well as sinners. Donal Dorr explains in his book, Option for the Poor: One Hundred Years of Catholic Social Teaching, that an appreciation of the roots of liberation theology begins with a reconsideration of the Church’s involvement in the oppression of indigenous peoples. In the commercial and political expansion of European nations into Asia, Africa, and Latin America, some popes saw an opportunity for the Church to bring the gospel to other countries. But the Vatican did not have ships of their own so the only way that Catholic missionaries could reach out to these distant lands was to travel along with the merchants, soldiers, and colonists from Portugal and Spain. But the popes conceded a great deal of power in this exchange, and gave Portugese and Spanish authorities the right to nominate bishops and to exercise some institutional control over the missionary churches in Latin America (Dorr, 67).

Donal Dorr explains that the Church gave little or no support to indigenous peoples struggling for independence in Latin America. While some Church leaders spoke out against the colonization policies of Portugal and Spain (including Bishop Bartholomew de las Casas’ attention to enslavement and forced conversions of indigenous people), there was no recognition among the popes that the whole process of European colonization was morally repugnant (Dorr, 69).

For example, popes Benedict XV and Pius XI both insisted that the sole concern of missionaries should be to gain souls and promote the glory of God. Both warned that clergy in Latin America should “never get involved in any of the political” issues and should exhort the people to faithfully obey the public authorities (Dorr 72).

This forms part of the the backdrop for the emergence of liberation theology. The Church’s reach extended all over the world, but sometimes Church leaders sided with the elites and not the people, in their struggle for political/economic liberation. Liberation theologians tried to initiate a shift in the Church’s perspective to recover the gospel roots of Jesus’ mission and identify again with the poor and marginalized.

Postcolonial scholars point out that the ongoing instability in many countries today results from the lingering effects of colonization. In other words, a country like Kenya is political “independent” from Great Britain but in fact often dependent upon former colonial powers politically, economically, and militarily. The same could be said of many other countries in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. Donal Dorr explains that the canon of Catholic social teaching and liberation theology has helpfully developed away from a paternalistic narrative of the good white European who saves the bad/poor/savage dark-skinned native, and that contemporary discourse calls for solidarity and the promotion of a just social order that ends the domination of some countries by others. Our hagiography deserves a similar updating.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks