This is the first of a periodic series—You Should Read This—on works worth reading.

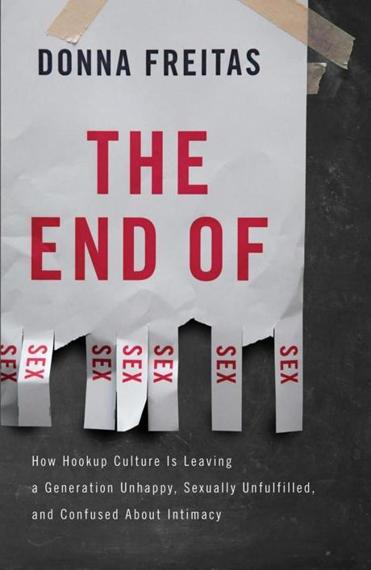

I always find Donna Freitas an insightful thinker. This was true in our days together in graduate school (a little disclosure here) and is definitely true in her recent follow up to Sex and the Soul, titled The End of Sex: How Hookup Culture is Leaving a Generation Unhappy, Sexually Unfulfilled, and Confused About Intimacy.

Her main point is one she has been building over the past few years. Freitas contends that the problem with hookup culture is that it is one of pretend and coercion. It is a culture that makes everyone believe that everyone is hooking-up and that everyone wants to hook-up. Sex is to be mechanistic, devoid of emotion, romance, and intimacy. Freitas describes it this way:

Hookup sex is fast, uncaring, unthinking, and perfunctory. Hookup culture promotes bad sex, boring sex, drunken sex you don’t remember, sex you could are less about, sex where desire is absent, sex that you have “just because everyone else is, too,” or that “just happens.”

This pretending results in a kind of coercion that affects all students, most negatively. It is not just that students feel like they have to participate but rather that they feel like there are no other options if the want to have any friends or a social life. Throughout The End of Sex, Freitas refines this argument and develops it in some pretty fascinating ways, four of which I note below.

1. Alcohol as abdication: Alcohol has long been known to be that which enables hookup culture. Freitas labels it the “all-purpose” solution, enabling people to go against their desire for intimacy and to hook up without emotion. It also provides a ready excuse for whatever happens. Freitas observes that, “so many students talk about how they relinquished agency for sexual decision-making because of alcohol.” Freitas notes two interesting consequences of this abdication. First, it points to most students’ dislike of hooking up, trying, it seems, to separate themselves from what happens. Second, and more disturbing for me, is that it makes identifying sexual assault and rape difficult. It is not that assaults do not happen, Freitas states, but that students find it difficult to recognize—caught in the double-bind of a coercive culture and an attenuate ability to consent—and, consequently, more difficult for institutions to protect against it. As Freitas writes,

Most sexual-assault programming . . . . centers on language—no means no and yes means yes—and the importance of gaining consent. This type of education is absolutely imperative and significant to the conversation, yet in so many ways it has also become useless in light of hookup culture.

2. Men suffer from hookup culture as well: If students do not want to participate in hooking up as demonstrated by its intimate link with alcohol consumption, why would they participate in it? The problem that Freitas and so many others note is that hooking up seems to be the only game in town, excluding all other options for meeting people, dating, or relationships. To be sure, there are some men and some women who want to participate (and enjoy it). Most, however, feel forced to do so. Freitas’ insight here is that it is not just women who are forced into this culture but also men. Hookup culture does “not so much cater to heterosexual men and male desire” but rather to their anxiety about living up to the expectations about what “guys” should be:

Women experience glass ceilings just about every which way they try to move, but men face an emotional glass ceiling. We ask that they repress their feelings surrounding their own vulnerabilities and need for love, respect, and relationship so intensely that we’ve convinced them that to express such feeling is to have somehow failed as men; that to express such feeling not only makes them look bad in front of other men, but in front of women, too.

3. Making it better: Freitas’ drive behind the book is to suggest ways to ease the suffering that so many students experience. Hookup culture not only thwarts healthy relationships that so many want but also compromises the dignity of so many participants. To respond, Freitas studies all sorts of possibilities, anything that presents a possible alternative to hookup culture: virginity, temporary abstinence, Abstinence Centers (an idea proposed by the Anscombe Society), dating, conversations about the meaning of sex and what good sex is, and attending to and supporting the practices of the LGBT community who has already had to negotiate alternatives to dominant sexual ethos. As Freitas notes, she is not advocating one to the exclusion of others, but rather advocating for all of them in hopes of developing alternatives that make the culture better for students and their relationships.

4. Professors can help: Freitas argues that professors can help students reflect on and find alternatives to hookup culture. She explains it best:

An effective response to hookup culture could be as simple as inviting students to apply critical-thinking skills to the task of evaluating their weekend activities; asking them to draw on their on-campus experiences as they discuss gender, politics, philosophy, literature, theology, education, and social justice inside the classroom; teaching them that their experiences are valid sources for evaluation . . . . Helping students make this connection between critical thinking and critical living is the best method for tackling the negatives of hookup culture.

While Freitas’ diagnosis of hookup culture is extremely helpful, her suggestions on how to respond are where her work most dovetails with Catholic moral theology. Freitas is concerned with how to ease the suffering of people and create a culture that fosters the dignity of human beings. This is the hope of so many us moral theologians, whether we are discussing politics, economics, the environment, or marriage. Freitas helps us to see that making places “where it is easier to be good” (to borrow a phrase from Dorothy Day) is just as important on our campuses and with our students.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks