“Speak fearlessly.” -Petr Stica (Germany)

“We need bold action.” -Emmanuel Katongole (Uganda/US)

“We must get away from wooden, dense, constipating discourse.” -Dennis T. Gonzalez (Philippines)

“Not without my sisters!” -Tina Beattie (UK)

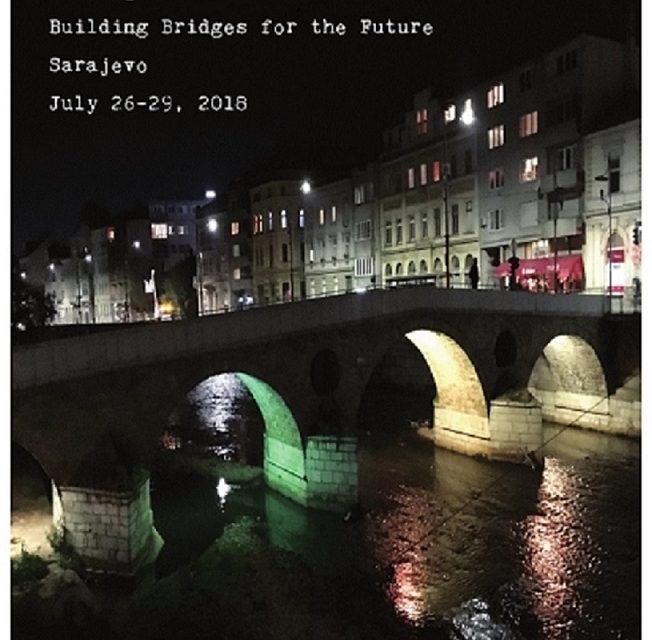

The Catholic Theological Ethics in the World Church conference took place two weeks ago in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Much has already been written on the conference, and many of the talks will be published in the edited volume that comes out next year. But those publications will have a hard time capturing the spirited discourse that emerged in the conference sessions and around meals. CTEWC, founded by Jesuit moralist James Keenan, brought together theological ethicists from around the world to learn from one another and foster networks of solidarity and support that can last beyond the conference itself. Joshua McElwee posted reports for NCR: on how the conference amplified the voices of women theologians and on the pope’s letter to the conference participants. NCR published Charles Curran’s plenary address here. James Keane covered the conference for America Magazine with reports here and here. I was so pleased that he focused on the voices of theologians from the Global South and the importance of dialogue and collaboration going forward. To these voices I will add my own reflections about what made the conference so meaningful and successful.

A Sense of Urgency

Traveling to Sarajevo was, for most attendees, a long trip. Upon arrival, many experienced jet-lag and the usual confusion that comes from arriving in a country where you don’t speak the language and aren’t familiar with the local culture and customs. At least I did. But there was an energy among the participants that came from a sense of urgency given the signs of the times in 2018. Stanislaus Alla, SJ, told us of how India is in crisis. I learned about Hindu nationalism and the challenge of bridge building in his context. Anne Celestine Oyier Ondigo Achieng, SFJ, told us of the structural injustices that persist in Kenya. She described a desire to move beyond a “blame game” and yet laid out thorny complex problems such as political corruption, climate change, gender injustice, and the power of multi-national corporations. Shawnee Daniels-Sykes lamented the crisis of hyperincarceration of young men of color in the US and the rise of neo Nazi/white supremacist rallies and hate crimes. Susana Nuin Nunez described conflict over land reform and extreme poverty. Victor Carmona and Alain Thomasset, SJ, addressed the danger faced by migrants at inhospitable borders. Alison Munro, OP, detailed the lack of funding for AIDS treatment in South Africa. Elio Gasda, SJ, decried the everyday violence of capitalism and militarism in the Latin American context. People spoke with such a sense of urgency: ethnocentrism and nationalism are on the rise and populist movements are a destabilizing force, we are already dealing with the effects of climate change and can’t agree on how to proceed, globalization fosters increased economic inequalities, and on and on. Many conversations I had with colleagues from around the world began with questions like “What is going on in your country? Do people of faith really support your president?” & “How is it that we know so much about what is going on in your country and you Americans don’t know what is happening in ours?” One kept hearing the word “crisis” — with the resulting head nods of “yes, we understand, and this should not be.”

On the Vocation of the Theologian

In the midst of these conversations, I began to notice that many of the conference attendees framed their work not primarily as contributions to the academy but as problem-solving in local contexts. The vocation of the theologian was described as one of engagement and orthopraxis. Charles Curran told us that it is not enough to determine what is right or wrong; we are called to act on behalf of justice and participate in the transformation of the world. Petr Stica told us of the need to speak fearlessly and overcome nationalistic tendencies toward solidarity. Michelle Becka urged us to be engaged in mainstream conversations and public theology, saying that “social ethicists must evaluate public discourse.” Emilce Cuda urged us to recognize that people are “concrete realities” and their lives demand attention to the complexity of their lived realities. The vocation of the theologian in these times involves immersing oneself in the reality of life in a particular context, reflecting on that reality in the light of the gospel, and acting for liberation in that context. This drive towards engagement and activism seemed natural and obvious to the participants, and seemed to express a pivot point for theological ethics in the Catholic tradition. Moral theology is not just a discourse about action. It isn’t enough to write about the issues. The question becomes, what are you doing as a result of what you are thinking and writing about?

A Reality Check

And then there were reminders of the transformation yet to be accomplished within the church. Making space for women in the church is an ongoing task; clericalism persists not only at the altar but in the seminary-pipeline through which women are excluded from theological education. Tina Beattie encouraged priests gathered there to begin to raise questions about their clerical privilege. “Not without my sisters” is an invitation for priests to refuse participation in events that exclude women. It is an invitation to consider how the church must practice what it preaches. If we are to be voices for justice and peacemaking and intellectual-activism, our voices will be more coherent when our own institutions live up to the values of justice and peacemaking and intellectual freedom. The church, too, must continue to resist a Eurocentric ideology or a paternalism which thinks all answers come from Rome. SimonMary Aihiokhai asked Charles Curran to think beyond the canon of Aquinas. Anne Celestine Oyier Indigo Achieng spoke of a necessary move from indigenization to inculturation. Dennis T. Gonzalez complained of “wooden, dense, constipating” terms and categories in traditional discourse. As moralists gathered, we were coming to appreciate both the urgency of the moral problems our world faces and the challenges of working in our ecclesial contexts to foster transformation.

Sarajevo Roses

Each day when I walked from the hotel to the conference, I passed a Sarajevo rose at the Cathedral Square. This is a reminder of the casualties during the seige of Sarajevo; in places where shell craters remain the sidewalks remain damaged but a frame has been installed around the damage and the crater is painted red. It reminds those passing by of the realities of war and of the wounds still born by this city and its people. Sarajevo roses are dangerous memories, conjuring grief and anger. But they also tell visitors to this city that its people are resilient and that peace is always fragile and in need of active work. Peace cannot be taken for granted. The past is in the past, but it informs the present, on which we build the future. I found these public displays of remembrance to be hauntingly beautiful, in part because of the juxtaposition of the damaged shell craters and the rebuilt lively town square around it. The tension between these two became for me a metaphor of the life of the theologian– on the one hand, the value of entering into the wounds of people’s everyday lives and our broken social structures, while on the other hand, offering a sense of hope in what Pope Francis has called the joy of the gospel.

What’s Next

I was very moved by the memorial service at the conference, and it invited me to reflect on my own vocation and life choices. As I listened to the life stories of moral theologians who have died recently, including two I knew personally (Sister Anne Nasimiyu and Fr Norbert Rigali), I let myself feel my grief and loss. I also listened to the ways in which each person was honored: for their publications, contributions to religious life/church, virtues. It prompted me to think about whether I am making the right choices in my own life, if I’m responding to the Spirit’s call on my own journey. In what areas of my life do I need to be bolder? In what areas do I need to be more engaged? Where is God calling me to join the work of transformation? I feel encouraged by the CTEWC network and the opportunity to remain in conversation with colleagues around the world as we all discern these questions for ourselves in our own contexts. For more on the conference including posters, schedule of events, and list of attendees, visit www.catholicethics.com.