The following is a guest post from Erin Brigham of the University of San Francisco

Since San Franciscans were told to shelter in place two weeks ago, families have been scrambling to care for children while working from home. My workday now starts at 4 AM. I work as much as I can before 10 AM when I tag my husband and begin my shift caring for our preschooler. Sleep deprivation is a minor concern compared to families who cannot work right now or cannot provide childcare during school closures. The work-life imbalance that many of us are experiencing during this pandemic, some more acutely than others, invites us to rethink old paradigms of family, productivity, and gender.

Catholic social teaching offers clarity and conviction during pandemic-times. As we experience the reality of our interdependence, the core principles of solidarity, the common good, and preferential option for the poor are evoked not only by religious leaders but by politicians and public health officials. But the church suffers a patriarchal blindspot when it comes to gender. Modern Catholic teaching simultaneously recognizes that women should be treated equally in the workplace but insists that her primary responsibility is in the home. The limitations of this teaching are exposed as families and employers are forced to renegotiate the relationship between work and home.

Like many women, I regularly experience myself straddling paid work and domestic work without a sense of completion or excellence in either realm. I catch myself operating out of deeply ingrained categories of public / private, work / home even though I don’t experience a neat separation of these realities. I recall many times I have phoned into a meeting while home with a sick child, feeling anxious that my colleagues would discover the reason for my absence and judge me as incompetent.

The difference now is that my husband and I are sharing this struggle and not trying to keep it a secret because our colleagues, men and women, are in the same boat. With schools closed and workers sent home, it is harder for any of us to hide behind traditionally gendered divisions of labor. I have no doubt that men also struggle to achieve work-life balance in a culture that too often defines us by our productivity. But the association of femininity and domestic work is deeply ingrained in culture, politics, and religion.

Pope John Paul II, whose writings on work and gender remain a touchstone for current Catholic teaching, reinforces the association of femininity and the home. In Familiaris Consortio he writes “There is no doubt that the equal dignity and responsibility of men and women fully justifies women’s access to public functions. On the other hand the true advancement of women requires that clear recognition be given to the value of their maternal and family role, by comparison with all other public roles and all other professions” (FC, 23). Like many feminists, he recognizes the simultaneous devaluation of domestic work and societal barriers for women in public life. He responds to these expressions of sexism by elevating the unique qualities of femininity as equally important but essentially different to masculinity.

Defending the value of domestic work and the work of care addresses a number of social problems. It challenges a culture that defines us by economic productivity and fails to support work-life balance with paid family leave and flexible working arrangements. It challenges an economy that under-compensates teachers, childcare providers, and other caring professions. How many of us, now asked to homeschool our children, have a renewed gratitude for teachers and caregivers?

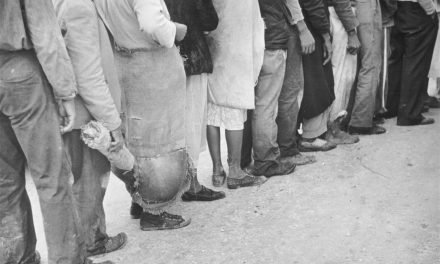

Others depend on domestic workers who, in most cases, are not allowed to come to work during shelter in place. Their work of cleaning houses and caring for loved ones is invisible in John Paul’s schema, a point developed by Catherine Osborne. Although it is in the “private” realm of the home, theirs is paid labor, a priority for justice in Catholic social thought. And right now, domestic workers, most of whom are women of color, are particularly vulnerable to loss of wages without recourse to sick leave or unemployment.

By rejecting the cultural fallacy that any individual, woman or man, can do it all, complementarity puts forward a potentially liberating anthropology. The paradox is that while gender complimentary aims to reinforce interdependence, it actually diminishes it with a narrow focus on a traditional nuclear family. Pope Francis’s Amoris Laetitia reinforces this as the ideal while recognizing diverse expressions of family. But Francis’s pastoral sensitivity does not imply a shift away from John Paul’s anthropology. He explicitly rejects “ideologies of gender” that deny complementarity (AL, 56).

Part of the revolution in thinking about home, work, and gender means recognizing the unique value of this work and allowing solidarity, not rigid conceptions of gender to guide how we organize work and family in our homes and society. John Paul II’s teaching on social life, also grounded in an anthropology of interdependence, is particularly relevant here. Solidarity is a virtue, he writes in Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, “not a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of so many people, both near and far. On the contrary, it is a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say, to the good of all and of each individual, because we are all really responsible for all” (SRS, 38).

Catholic teaching regards the home as a primary space for cultivating virtue, describing it as the domestic church. I have struggled with this image due to the implicit and explicit ways it reinforces male headship in the family, as in ecclesial structures. However, as Lisa Cahill has pointed out in Sex, Gender, and Christian Ethics, this notion of domestic church, when rooted in the Gospel, offers a subversive social ethic. Jesus challenged the patriarchal family structure by preaching an expansive notion of community that embraced not only kin but the outcast. This social ethic based on a preferential option for the poor and vulnerable, recurring in the Hebrew scriptures, was central to Jesus’s teaching on family and discipleship.

On the third Sunday of Lent, the first Sunday mass was cancelled to observe social distancing measures, I gathered my family around our table and called us to prayer. My husband did the readings and my five year-old opened the meaning of scripture. It was the story of the woman at the well. Without prompting, my child told us the story is about being a good friend. My preschooler, who has yet to encounter Aristotle, articulated the foundation of virtue, leading our family into a deeper understanding of the Gospel.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks