This is a response to two poems: “Seekin the Cause,” by Miguel Pinero, and “Yo Soy Joaquin,” by Corky Gonzales. Additionally, it is a theological refutation of Octavio Paz and his caricature of the Chicano male, the pachuco clown, found in the first chapter of The Labyrinth of Solitude. I share this as a gesture of reception to the call and invitation given in the Apostolic Letter Patris Corde.

***

Looking for Work with Saint Joseph the Worker

by Miguel José Romero, on the feast day of Saint Joseph the Worker, 2021.

I wonder — with ol’ Joaquin, both saint and son —

lost, confused, and seekin’ a cause:

Where will roads meet and intersect…

...when I can be more than a half-holy,

half-man dodging border checks with saintly wife.

Slipping baby, past boundaries, that surround cities

with no room to spare for crossbreed, mestizo families:

Blessed Mother, Holy Child…and voiceless me,

an heirless, jobless, lowbrow accessory.

Seekin’ the cause, but the baby’s cryin’ —

so I get up, man up, and hustle — to keep it real

amid the tricks of status, violence, cash —

alpha male crack, tweaked to trap: justice,

my honor, and a half-dreamed angel’s call

to be a man who redefines macho.

Though our homeland is — past the red Rio sea,

the not-yet of Aztlán weighs heavy.

Where you goin’, ese? I don’t know, ese. Pues,

found out, we move on, to the next town — and I wait

for my cause — peeking, hiding, teasing me;

we pray, we survive, and I look for work.

I worry, almost busy; I doubt, almost despair;

but then I feel You, baby’s breath in my soul —

I believe You — and You help me to believe:

que los pobres en espíritu guarda la fé.

In little brown eyes and the Mother’s chaste embrace

are this poor man’s hope for a good life — ánimo.

So, when our life breaks on my wet back,

your besos give me courage — échale ganas.

This time’s not to kill me, but to raise me,

so I can help raise You—my Hope—to be found:

the dignity and destiny of the imago dei…

My Cause on my shoulder — adelante, hombre.

Ita, a family man—and I live between: working…

in places I’m not supposed to be — I’m speaking…

languages that aren’t mine to revise — I’m taking…

chisme about my pedigree, my family — for a child:

a bridge, who might be torn down, cross-wise,

by people of hate, who You love,

and though I want to hate, for loves sake, You —

You tell me my name: papa — and give me cause, saying:

hito, you are My mestizo, My cross-breed —

man called for the cross—ing of a different river,

to be a good coyote for mothers, children,

and tongue-tied fathers who pass babies over fences.

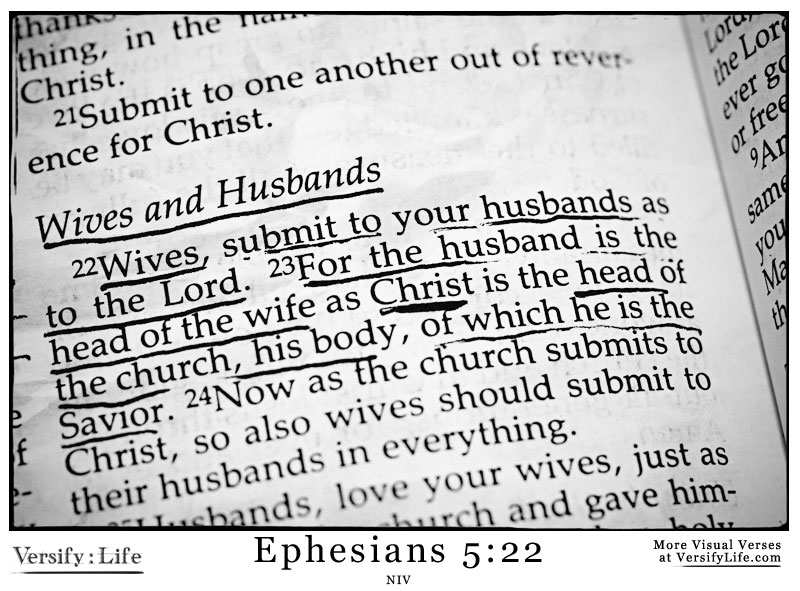

True macho who loves justice, respects woman,

and hustles for his family; dignified man

who suffers indignity, for a dusty dream

about refuge, honest labor, and hope; un buen patrón

who hears his name in a mid-day whisper,

and carries the cause of fathers who look for work.

***

Some background information: About fifteen years ago a friend pressed me to write something theological engaging Miguel Pinero’s poem “Seekin the Cause” (performed here by Benjamin Bratt; text) and Corky Gonzales’s “Yo Soy Joaquin” (video and text). What caught my attention was the way those two pieces cast manhood, machismo, strength, and masculine identity (both poems were written as performance pieces). At the same time, I was haunted by Octavio Paz’s caricature of the North American Chicano male, from the first chapter of The Labyrinth of Solitude: a fearful, posturing, violent, culturally clumsy, and profoundly vulnerable ‘pachuco clown.’ …and then I thought of Leo XIII and the moral witness of Cesar Chavez (see F.J. Dalton and M. Garcia). The poem was finished when the escape to Egypt described in Matthew 2:13-15 became the central image:

When they had gone, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream. “Get up,” he said, “take the child and his mother and escape to Egypt. Stay there until I tell you, for Herod is going to search for the child to kill him.” So [Joseph] got up, took the child and his mother during the night and left for Egypt…

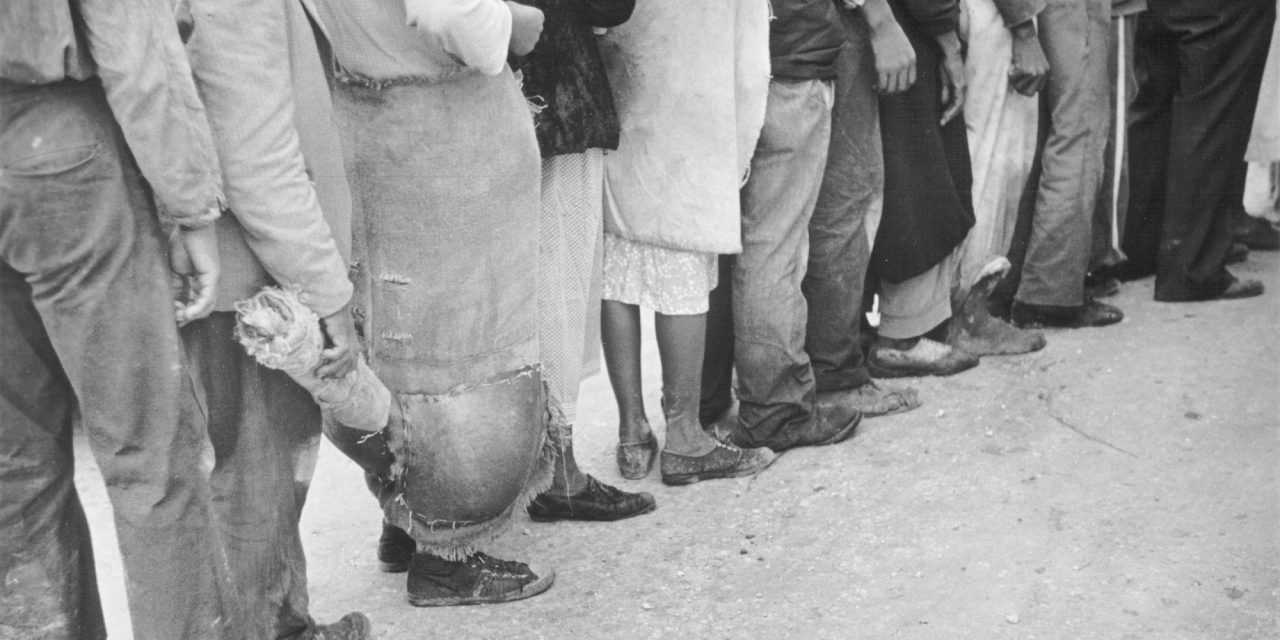

Whatever the ancient, near-eastern Egyptian equivalent of the lumberyard was in the first century, St. Joseph was standing out front of it looking for work. According to the Catholic tradition, he left behind key markers of ancient masculinity, social status, and virility: He was chaste and was not sexually intimate with the Blessed Mother. He wasn’t the father of the child he was raising. Powerless, he and his family were on the run from the violence of the political authorities. St. Joseph didn’t speak the language of the land where he was living with his family. Whatever credibility and social capital he had built in his life had been left behind.

What was going through his head? What was he thinking? What does righteous manhood and holy masculinity look like in that circumstance?