Francis Makes Migration a Key Issue

Pope Francis is not the first pontiff to advocate for migrant rights, but it is an issue that he has made a priority in his papacy. In July 2013 Francis kicked off his papacy by traveling to Lampedusa, Italy, an island about 70 miles off the coast of Africa in the Mediterranean Sea. Lampedusa is known as a waypoint for migrants; the pope went there to highlight the perilous journey that so many migrants face, a journey faced by Jesus as an infant, a journey that has led to death for over 46,000 migrants since 2000, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Catholic Roots

Catholic values find their roots in the theological claim that God is love, and that humans are created imago Dei, in the image of God, the image of Love. The principle of human dignity in Catholic social thought affirms the inherent value of each person, no matter their race, gender, creed, sexual orientation, ability, ethnicity, citizenship, or any other marker of individuality and intersectionality. Every person is precious to God. Every person must be treated with respect.

God’s love is inclusive and the challenge Christians are called to take up is a challenge to model our lives after the life of the incarnate God, Jesus of Nazareth, that radical 1st century Jew who preached a gospel of radical equality, criticized unjust social structures, practiced inclusive table fellowship, and emphasized mercy and healing. The gospels don’t tell us a lot of stories about Jesus getting angry, but when they do, Jesus directs his anger at people whose abusive use of power demeans and dehumanizes vulnerable people. Telling also are those stories in which Jesus has compassion for those whose moral blindness prohibits them from recognizing the dignity of their fellow human beings. For all who follow Jesus today, we face a constant challenge to uncover our own moral blindness and habits of exclusion. Jesus did not just eat with outcasts and so-called “sinners”—prostitutes and tax collectors. He identified with those most vulnerable, telling his followers “whatever you do for the least of these, you do unto me.”

From the perspective of the gospels, to be inclusive means honoring the inherent dignity of each person; recognizing the need to learn from each other; admitting that one person cannot have the fullness of truth but that we must listen to one another and learn from the experiences of people different from us.

Self Reflection

What does that mean for me, an educator at a Catholic university in a border town, in a week in which “build the wall” rhetoric is escalating and politicians are negotiating the terms of the federal budget and trying to decide if funding of the border wall will be a part of the deal-making? My life is a lot like what Beth describes in her post about middle-class America. I drive a mini van. I have two kids. I confess that I am prone to spending too much at Target.

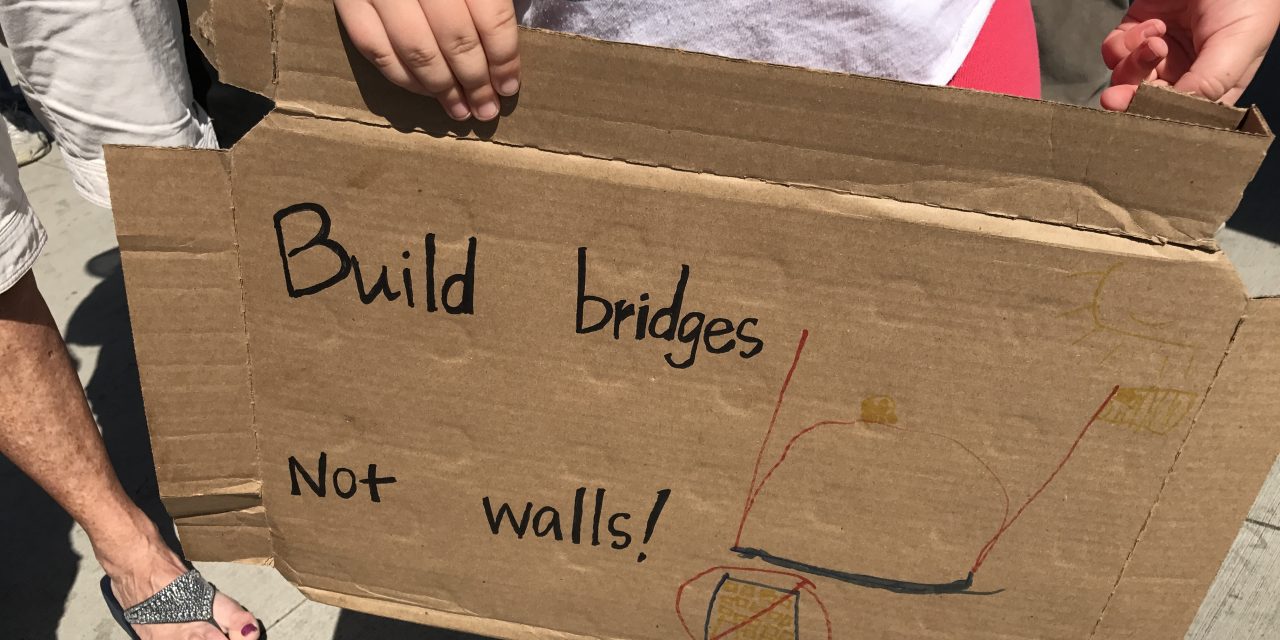

But this week, I had to protest the wall. I had to drive that minivan down to San Ysidro and join the faith leaders of my community who were speaking out as Homeland Security Secretary Kelly and Attorney General Jeff Sessions toured the border facility after recently calling border towns war zones. Without any attention paid to the push/pull factors underlying migration flows, the complicity of US companies and US consumers who depend on produce and products that require the labor of undocumented persons, or any attention to the role the US has played in shaping politics in Central and South America, the current administration seems to think that an expensive border wall will bring an end to illegal migration.

I think part of my job requires fostering empathy for migrants and undocumented persons, recognizing with fresh awareness my complicity in unjust social structures, and reaffirming my aim of changemaking for the common good. It means challenging the rhetoric of “America First” and fostering instead renewed attention to social justice and the common good. Build a wall? No thanks. Let’s aim higher. Let’s think beyond nationalist rhetoric and instead foster awareness about our complex systems of interconnectedness in a globalized world. Let’s create momentum for social justice. Of course, that doesn’t mean the problems are less complex. Instead, as I read books like Seth Holmes’ Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies, I realize with deeper anguish that the sweet blueberries I like to throw in my morning smoothie don’t taste as sweet when I understand the racial hierarchies at a typical US farm, and the exploitation of labor migrants working in the agricultural sector of our economy. We have to pay attention to this suffering and work together to figure out better long-term policies rooted in social justice.

I think part of my job requires fostering empathy for migrants and undocumented persons, recognizing with fresh awareness my complicity in unjust social structures, and reaffirming my aim of changemaking for the common good. It means challenging the rhetoric of “America First” and fostering instead renewed attention to social justice and the common good. Build a wall? No thanks. Let’s aim higher. Let’s think beyond nationalist rhetoric and instead foster awareness about our complex systems of interconnectedness in a globalized world. Let’s create momentum for social justice. Of course, that doesn’t mean the problems are less complex. Instead, as I read books like Seth Holmes’ Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies, I realize with deeper anguish that the sweet blueberries I like to throw in my morning smoothie don’t taste as sweet when I understand the racial hierarchies at a typical US farm, and the exploitation of labor migrants working in the agricultural sector of our economy. We have to pay attention to this suffering and work together to figure out better long-term policies rooted in social justice.

Mining the Documents of CST

The two principles of human dignity and preferential option for the poor both play significant roles in shaping Catholic discourse about immigration and justice today.

In his 1963 encyclical, Pacem in Terris, Pope John XXIII said that every human person has rights and obligations that flow from his/her very nature; these include the right to emigrate and immigrate (8-27). In that document, the pope argued that “the fact that one is a citizen of a particular state does not detract in any way from his membership in the human family as a whole, nor from his citizenship in the world community.” (par. 25).

The pope’s argument here invites all of us to consider our common humanity as prior to any identification of national identity, citizenship, or social location.

Fourteen years ago, the United States Conference of bishops issued a joint statement with the Mexican bishops on migration. That statement, available for free online, is called Strangers No Longer, and builds on the teachings of Pope John XXIII. The five principles that emerged in that document are:

- Persons have the right to find opportunities in their homeland.

- Persons have the right to migrate to support themselves and their families.

- Sovereign nations have the right to control their borders.

- Refugees and asylum seekers should be afforded protection.

- The human dignity and human rights of migrants should be respected.

As one can see, a tension emerges in the document between the legitimate right of the state to control borders and the human rights of migrants. In my context, the increasingly militarized border 17 miles from my university’s campus often privileges the first and too often ignores the second. But the bishops name limits to the right of the state, for example in paragraph 39, they say:

The Church recognizes the right of a sovereign state to control its borders in furtherance of the common good. It also recognizes the right of human persons to migrate so that they can realize their God-given rights. These teachings complement each other. While the sovereign state may impose reasonable limits on immigration, the common good is not served when the basic human rights of the individual are violated. In the current condition of the world, in which global poverty and persecution are rampant, the presumption is that persons must migrate in order to support and protect themselves and that nations who are able to receive them should do so whenever possible.

In other words, the state’s right to control borders is not absolute, but is only legitimate when in support of the common good. The US Catholic bishops have continued to update their teachings over the years, most recently calling for a series of reforms to the broken US immigration system; for example, they advocate for an earned legalization program and temporary worker program with appropriate worker protections; greater efficiency in handling family-based immigration cases; and restoration of due process for migrants. The USCCB has argued that all undocumented persons in the US should “have opportunities for a safe home, education for their children, and a decent life for their families,” and have called for an end to the practice of separating families through deportation.” (FCFC 52).

Conclusion

Catholic values will carry different messages depending on one’s own social location. Recall that when we use the word gospel we mean “good news”. I would argue that Catholic teachings on immigration and inclusion are “good news” today for those who are undocumented, scared, marginalized, or threatened by the anti-immigrant and anti-refugee policies and rhetoric of the current administration.

For well-educated, white, well-fed, privileged US citizens like me, these teachings are unsettling and challenging. They challenge my complacency, they remind me that while I go about in the regular tasks of my day, many others around the world are engaged in a struggle for survival, a struggle to be recognized as human. I would like to say that I am in solidarity with them in their struggle. But would it be honest? Am I really? I think it would be more honest for me to say “my heart aches as I begin, ever more each day, to realize the brokenness of our world.” There is still so much I need to learn, and so much more I need to do. I can vote. I can contribute to charitable organizations and political campaigns aligned with my values. I can teach my children to celebrate cultural difference (like a Sunday afternoon at Chicano Park).

There is always more to do. I’ll keep reading, especially as new books by Liz Collier and Tisha Rajendra will contribute to shape Catholic discourse on these issues. But I also think that sometimes it is just important for white people to show up to the protest and listen.