The late Jesuit theologian Bernard Lonergan was fond of reminding people that knowing is NOT “just taking a good look”. Acquiring knowledge, Lonergan argued throughout almost all of his works, is a dynamic process that requires the accumulation of insights, correct insights, by a community of people. Although Pope Francis does not rely on Lonergan (even though they are both Jesuits), his view is very similar in Lumen fidei. Pope Francis (and Benedict) emphasize that faith is not a thing, “already, out there, now, real”, but rather knowledge emerging from personal relationships. David Cloutier noted in his “First Look” at the encyclical that faith is about “standing”. I agree but want to add it is also about standing with others, including God.

Francis makes the claim that we come to faith through others in several places but no more clearly than when he says,

Faith is not a private matter, a completely individualistic notion or a personal opinion: it comes from hearing, and it is meant to find expression in words and to be proclaimed. (§ 22)

In fact, in Lumen fidei, Francis goes on to say that without others we could not know at all.

The transmission of the faith not only brings light to men and women in every place; it travels through time, passing from one generation to another. Because faith is born of an encounter which takes place in history and lights up our journey through time, it must be passed on in every age. It is through an unbroken chain of witnesses that we come to see the face of Jesus. But how is this possible? How can we be certain, after all these centuries, that we have encountered the “real Jesus”? Were we merely isolated individuals, were our starting point simply our own individual ego seeking in itself the basis of absolutely sure knowledge, a certainty of this sort would be impossible. (§ 38)

On the one hand, this claim is not new. Even before Peter Berger’s The Social Construction of Reality, we’ve know people both depend on others for knowledge and construct knowledge. (This is why Michael Hannon over at Patheos quipped that the encyclical should be called “After Faith”, riffing off of MacIntyre’s After Virtue.) On the other hand, Francis highlights how knowledge, all knowledge, including faith, is a gift from one person to another. It is to be shared and, in being shared, it increases rather than diminishes. Others can know what we know and they can go beyond it in new and fascinating ways. This is the hope of teachers and parents.

Yet, knowledge as social and relational should give us pause for concern in two ways. First, alone, this might make knowledge seem relative and arbitrary. It might make knowledge and, by implication faith, whatever the group–the dominant group actually–decides what it is. Thus, the second concern is that knowledge unhinged from any foundation can be manipulated to serve the ends of the powerful. Francis notes this, twice warning of totalitarianism (see § 25 and 34).

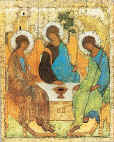

Francis’ foundation of faith is not an abstract principle though. He grounds it in a person (actually three persons who have one nature), God.

The word which God speaks to us in Jesus is not simply one word among many, but his eternal Word. God can give no greater guarantee of his love, as Saint Paul reminds us. Christian faith is thus faith in a perfect love, in its decisive power, in its ability to transform the world and to unfold its history. “We know and believe the love that God has for us”. In the love of God revealed in Jesus, faith perceives the foundation on which all reality and its final destiny rest. (§ 15)

Although Christians profess this God as being both all powerful and all knowing, this is not the foundation to which Francis appeals. It is God’s love, incarnate in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, that is the foundation. It is a relationship but one where God shares his own life and being.

In faith, Christ is not simply the one in whom we believe, the supreme manifestation of God’s love; he is also the one with whom we are united precisely in order to believe. Faith does not merely gaze at Jesus, but sees things as Jesus himself sees them, with his own eyes: it is a participation in his way of seeing. (§ 18)

God offers God’s very life to us, desiring for us to share in a life of joy and peace. God is not Zeus who punishes Prometheus for stealing knowledge of fire. God walks with us in the “breezy time of the day” (Gen 3:15), give us hearts of flesh and blood (Ezekiel 36:26), and comes to give us “life and have it more abundantly” (John 10:11). Faith is an overflowing knowledge given by God to all and to be shared between each other. It is the knowledge of love and that knowledge grows as it is shared.

Given this relational aspect of love, it should not be surprising that true faith is inclusive, bringing people and ideas together in bonds of love.

Anyone who sets off on the path of doing good to others is already drawing near to God, is already sustained by his help, for it is characteristic of the divine light to brighten our eyes whenever we walk towards the fullness of love. (§ 35)

Anyone of good will is already in relationship to the God who is love is our friend, a giver and receiver of knowledge and joy. (Fr. Landry makes this point in his NCR essay.) When he cites Newman, Francis makes clear this inclusive dimension saying, faith has the

power to assimilate everything that it meets in the various settings in which it becomes present and in the diverse cultures which it encounters, purifying all things and bringing them to their finest expression. Faith is thus shown to be universal, catholic, because its light expands in order to illumine the entire cosmos and all of history. (§ 48)

Faith does not start with the Cartesian doubt of everything and everyone but with a trust that “bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things” (1 Corinthians 13:7). It seeks to bring all people and ideas together through bonds of charity. (In his commentary, George Weigel also notes the way in which the encyclical indicates this expansive notion of the faith.)

Thus, for Lumen fidei, faith is the knowledge emerging in the the midst of loving others and God. It points to the God who is love and the love we are to practice. Let us go and practice love so we might find faith and truth.

It seems that faith is larger than any conception of it we could have. Faith might be compared to water, taking an infinite variety of paths in it’s search for the deepest ground.

Perhaps Lonergan is confusing his own personal faith experience with a universal “THE faith experience”, a very common error most of us would be inclined to make, one I will likely now make myself.

Some experiences of faith are not built of knowledge, beliefs, ideology and other products of thought.

A “trust that bears all things” can also arise from a “Cartesian doubt of everything and everyone”. Once a process of Cartesian doubt reveals that none of us know what we’re talking about on issues infinite scale, a search for faith in the products of thought may gradually melt away, and the trust may arise organically on it’s own from the resulting silence, a flower emerging from the ground on it’s own, independent of the gardener.

As seen from one limited human mind, faith built of ideology might be more precisely described not as faith, but as a desire for faith. It’s as if we hope that by the determined management of concepts we can domesticate faith, and bring it under our control.

But faith is not a machine or math equation, and faith is not fair. Faith is a force of nature, like the wind, and it goes where it pleases.

In my house, faith lands upon the unworthy, those apparently most in need, while skipping merrily and seemingly unfairly by those whose lives are already fully committed to love in action. One favor of faith might be the understanding that love is enough, sufficient unto itself, requiring no further embellishment.