Second Sunday in Ordinary Time

Isaiah 62:1—5

Psalm 96

I Corinthians 12:4—11

John 2:1—11

This Sunday’s readings invite us to think about marriage as a sign of God’s covenantal relationship with Israel, which the Church believes has been “consummated” with the incarnation. The prophetic traditions of Israel, especially Isaiah, present God as an eager bridegroom who passionately desires and delights in his bride. God does not merely desire to enjoy and possess Israel, but to transform and glorify her. Like any human spouse, Israel takes on a new life and receives a new identity as she is united definitively to her bridegroom. “No more shall people call you ‘Forsaken,’ or your land ‘Desolate,’” declares the prophet, “but you shall be called ‘My Delight,’ and your land ‘Espoused.’”

With this prophetic metaphor in view, St. John masterfully narrates the pivotal event that inaugurates Jesus’ public ministry in Galilee. The occasion for this first of Jesus’ “signs” is a wedding in the village of Cana. I find it interesting and suggestive that Jesus’ presence there is mentioned only after his mother’s: John tells us that Jesus’ mother was there, and that Jesus and his disciples were also invited. We have no indication whose wedding it was, but presumably these were people with whom the holy family, or perhaps only Mary, was familiar. John also notes that the wedding took place “on the third day,” which of course could be read as an allusion to the resurrection, though I’ve always liked to imagine that the feast itself was on its third day, which incidentally might help explain why the wine ran out.

The more likely explanation for why the wine ran out, however, is that the family celebrating this marriage was poor. If we are to place ourselves within the unfolding drama of this scene, it might be best to imagine this event as a rare “peak moment” in the otherwise grueling lives of a poor family living at subsistence level in a provincial backwater of the ancient world. These ordinary people would have encountered scarcity at almost every point in their lives, and here it is again—at the one moment designated for celebration, the one day when the fear of scarcity was to be set aside. And so the wine ran out. The wine, of all things: the very symbol of that bliss and buoyancy of heart which everyone came together to share.

Who then do we find most sensitive and responsive to this development? It is not Jesus—the divine Bridegroom incarnate—but rather, his mother: the woman whose own marriage was haunted by social disgrace and whose “birth experience” took place on the cold floor of a cave filled with livestock instead of family. She could not have been oblivious to what the bride must have been feeling at that moment, and she certainly did not stand idly by.

My students seem to connect with this story, I think, not only because Jesus provides large amounts of alcohol to a sputtering party, but also because Mary acts a little bit like a helicopter parent here. It is not as if Jesus has not already begun to direct his own adult life by this point—his disciples are there with him, after all—yet here is Mary still trying to tell him what to do. Not directly, of course, but by that most potent of familial tactics: passive aggression. “By the way, there is no wine.” “Yes? So? And? You want me to do what about that right now?” It is heartening to think that Jesus assumed even this aspect of human familial relations.

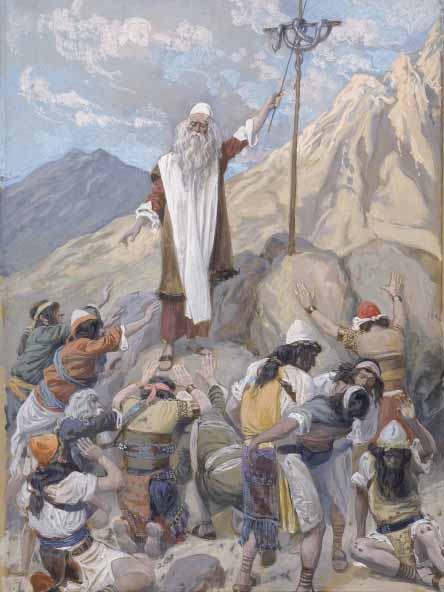

The more lofty way to read this exchange, of course, is to place Mary in the role of the prophet mediating between Israel and God. It is the cry of Israel that the wine—the spiritual vitality, the joy, the prosperity, the life which was promised them—has run out. The day of the Bridegroom’s coming has arrived, and yet she finds herself unprepared for the feast. It is the prophet who cries out to God on her behalf: have mercy! How long will you be silent? How long will you hide your face? Do something to save us! Jesus, holding to the prophetic pattern, is not interested in merely distributing hand-outs. Yahweh in the flesh, he desires rather a faithful covenantal relationship. And so, like the prophets, Mary tells the servants to “do whatever he tells you.”

With these words we see that the drama of the wedding feast has fully recapitulated the perennial drama of the people of God. Will Israel obey Yahweh or not? Obedience reveals itself as the key to the abundant wine of God’s life, which in the end is the only thing that will make us truly happy.

It is also therefore the key to a happy marriage (though I should hasten to mention that such obedience in the context of marriage must be first and foremost toward God, and fully mutual toward one another). In sharing the wine of matrimony, two individuals become not merely partners but spouses. Theirs is no longer merely an aggregation of resources and a balanced interaction of duties and responsibilities. Theirs is a common life that gives rise to an authentic communion of persons. Partnerships can be divided, cashed out, distributed. Marriages, however, are a truly common good: while the various assets involved in a marriage can be pieced out in pre-nuptial agreements or divorce settlements, the marriage itself cannot. It can only created or destroyed in toto.

Marriage is thus the most powerful of signs for the covenant which God desires to creates with his people. One cannot enter into it halfway, nor can one preserve any “core” of one’s own self-conceived identity from its transformative effects. Like marriage, participation in the divine life cannot be seized or earned, but only received and gratefully accepted. The analogy is an easy and straightforward one, in so far as both are ultimately and only about love. No one can successfully “acquire” love, but like God himself (who is nothing other than love) it begins to appear out of the corner of one’s eye only in the course doing other things. It is the horizon that informs all the concrete acts of obedience that constitute relationships of unwavering commitment, whether those be the everyday tasks of preparing meals, punching a clock and changing diapers, or the more dramatic deeds of suddenly relocating to a foreign land, submitting to an angel’s message or transforming 90 gallons of water into premium quality wine.

I only take issue with Christ’s reluctance toward Mary. It is a misimpression dumped on all of us by virtually all English translations of the Cana interchange.

The nab Bible like almost all Bibles distorts the interchange. It reads:

* [And] Jesus said to her, “Woman, how does your concern affect me? My hour has not yet come.”

That is what is called sense for sense translating. Word for word translating as in the Latin Vulgate has no such rebuke by Christ: ” What to me and to thee? My hour has not yet come”. Here’s the story of this passage.

The problem is that Augustine’s and Chrysostom’s negative take on the Christ/ Mary interchange weighed on Western interpreters but more importantly on Western translators. Almost all Bibles therefore in English took the liberty of translating the moment in a “sense for sense” fashion rather than in a “word for word” fashion. Christ literally says to Mary, ” What to me and to thee”. This phrasing used at least ten times in the Bible is neutral rather than antagonistic.

The English translations are all antagonistic on Christ’s side…some bad, some worse. It’s actually simple if you stay with the original literal words of Christ. Mary was worried to death that if Christ did His first public miracle there at Cana, He would be seized, imprisoned, and enter his predicted passion very soon. Simeon’s two part prophecy of both Christ suffering and her soul being pierced lived in her heart ever since that day. When Mary saw Christ enter the wedding with His recently picked first disciples, her heart must have skipped a beat. He was beginning His ministry…not as many experts thought resisting Mary’s call to a first miracle. Therefore, Christ was assuring her that He would not enter his passion that quickly. So to review the scene: Mary needs a miracle but is conflicted that it will lead to Christ’s passion very quickly and this worry shows greatly on her face as she petitions Christ; Christ sees the worry on her face and responds by assuring her…” what to me and to thee…my hour ( to suffer the passion) has not yet come”. Bingo. Mary hears a YES and immediately acts on that yes by telling the servants to follow Christ’s instructions. Lesson: sense for sense translations are not always a good thing. Stick with the Vulgate in this passage…which is the official translation of the Catholic Church in disputed passages.

Thanks for this thoughtful comment, Bill. I was a bit too flippant with that passage. Certainly Jesus’ reply need not connote any disrespect or annoyance, which many translations seem to convey, including the one used in the American Catholic lectionary. Just as Mary’s question to the angel at the annunciation did not connote any lack of faith, Jesus’ response to Mary’s statement need not imply any resistance.

Your interpretation of the exchange is new to me, though very intriguing. My only reservation in embracing is that it would require a great deal of speculative presumption about the meaning of Mary’s initial remark to Jesus. It is a plain indicative statement, which on the face of it seems to indicate that Mary is informing Jesus of something. It does not seem to be in any way against the rule of faith to read that statement as Mary presenting Jesus with another’s need, with full confidence that he will respond to it. That is what Mary does, after all: she intercedes with her son on behalf of us all, especially the poor and those in urgent need.

You are completely right, however, to make more of the term “my hour” than I have here. In using that term, John not only associates this event with Jesus’ passion, but places that association in the minds of Jesus and his mother. What was it about that situation that evoked the prospect of Jesus’ suffering and death? Is John implying somehow that Mary already perceives the central importance wine will play in the ongoing re-presentation and reception of her son’s redemptive passion? That is a very intriguing idea, at least to my mind.

If such an association is already at work in Mary’s mind and heart, then it is true that Jesus’ reply comes off as more of a consolation than a rebuke. Yes, I very much like that reading.

I just would not want to make too much of Mary’s “fear”, not only because she was without sin but also because the text clearly portrays her as bringing another’s need to her son, which in turn initiates his response. Mary does not obstruct or resist the miracle, but facilitates it.

It’s only a plain indicative statement by Mary if we keep her existential emotions out of the passage which we as men often are not sensitive to…including me. Her life context includes the Simeon two fold warning that both Christ would suffer and a “sword thy own soul shall pierce”.

That Christ had just that week picked the first disciples and publicly then brought them to a public wedding was an unprecedented moment for Mary…and not a week emotionally like any other week in her life. She then would have emotons that week of fear as she had long ago when Christ at 12 was missing from the caravan: Luke 2:48 nab version…” When his parents saw him, they were astonished, and his mother said to him, “Son, why have you done this to us? Your father and I have been looking for you with great anxiety.”. In your second to last sentence, you exclude fear because she is without sin but Luke 2:48 is telling you from her mouth that she can have great anxiety. We in the West are all Stoic heretics of a sort…..perfection means no fear to the Stoic and to us. But Mary told us we’re wrong about that in Luke 2:48. Christ’s picking the first disciples begins the march to both their sufferings but Mary did not have our hindsight as to how quickly Christ’s witnessing would lead to both their passions. For all she knew, it could be quickly rather than the several years we know by hindsight. To my knowledge, Miguel Migens first noticed that Augustine and most others had gotten wrong which “hour” Christ was speaking of: they said the hour of going public…Migens said the hour of the passion because words in John’s gospel are very symbolic not merely empirical and “hour” in John means the hour of Christ’s passion. Nor I would add myself did Augustine notice that Christ already began the ministry by picking the disciples that week and then went to a public event with them.

Augustine had tons of conflict baggage with his mother Monica who tried to convert him from both fornication and manichaenism for over ten years. In my opinion, that baggage made him see conflict here between Christ and his mother where in fact, assurance by Christ was taking place. Augustine and his myriad followers on this passage could never explain how Mary heard a yes from Christ immediately. The logic of their exegesis is that Mary was hearing a no. And yet she

immediately instructs the servants to obey Christ. That reaction of her nullifies all “Christ as resisting her” interpretations. But those interpretations led to the awful English sense for sense translations that one can compare at a Bible search engine site like blue letter dot com. Remember, the Reformers loved Augustine so their translations were also based on such interpretations. The King James perhaps gets the prize for the rudest Christ: ” Jesus saith unto her, Woman, what have I to do with thee? mine hour is not yet come.”

Awful beyond measure and makes Mary’s hearing of a yes downright delusional. The Douay Rheims was correct all along because it followed the Vulgate not Augustine and his mother/ son conflicts.

P.S. Patrick,

There is an unusual foretaste of the Cana event in 2 Kings 3 where the king of Moab, after Ahab’s death, ceases to give tribute to the northern kingdom ( Israel/ Samaria) so the King of Israel/ Samaria gets the kings of Edom and of Judea to join him in war against the king of Moab but they soon are running out of water for their horses and they petition Eliseus who tells them to place catch basins in the dry wadi. Water miraculously comes from the direction of Edom and fills the catch basins. The Moabite enemy because of the angle of the sun see the water as red and as blood and attack thinking the three kings have fought amongst themselves but the three kings then defeat them.

Water filled catch basins turn red as blood by a trick of the sun ….water jars of purification water are turned into wine at Cana which stand for Christ’s blood replacing the old law water.

The plot thickens….when they first approach Eliseus for this water help, Eliseus in the Vulgate says to the king of Israel… “ Quid mihi et tibi est? “….what to me and to you.

2 Kings 3:13. It is not out of the question that Christ and Mary had discussed this “water become red” scripture prior to Cana and it’s odd idiom “what to me and to you”….which idiom in the Vulgate appears also in 2 Sam.16:10 ( not water/ blood involved though in that case).