Sunday, September 14, 2014

Twenty-fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time

Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross

Nm 21:4b-9; Ps 78:1bc-2, 34-35, 36-37, 38; Phil 2:6-11; Jn 3:13-17

“For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world might be saved through him” (Jn 3:17). The Gospel from this Sunday’s readings boldly proclaims a message of salvation rather than condemnation. And yet, one cannot be faulted if there is still some confusion about the matter.

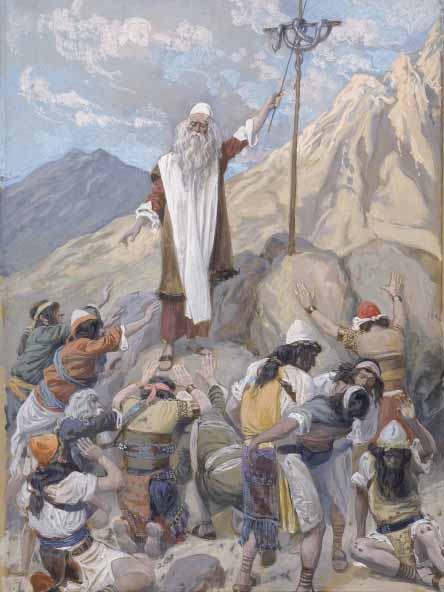

The first reading from Numbers finds Moses and his people in the desert. The people cry out to God in complaint over the meager and wretched provisions, wondering why they have been brought out of Egypt just to face this plight. Next we learn that God takes action: “In punishment, the LORD sent among the people saraph serpents, which bit the people so that many of them died. Then the people came to Moses and said, ‘We have sinned in complaining against the LORD and you. Pray the LORD to take the serpents from us’” (Num 21:6-7). God instructs Moses to craft a bronze serpent which, when gazed upon, will save any who had been bitten. Ultimately, salvation prevails. But what are we to make of God’s punishment that seemed to create the entire serpentine crisis to begin with?

This is not the only instance in Scripture where we may struggle to understand the meaning of punishment and suffering. Both the Old and New Testaments present additional challenges. And of course an enduring theological query is whether it was necessary for Chris to suffer and die. Couldn’t an all-powerful God choose another way to redeem God’s sinful people?

We should be wary of simple answers that explain away all the tensions. Still, it may prove fruitful to contemplate the character of punishment and condemnation. In particular, we may find instructive a concept from the field of criminology: reintegrative shaming.

John Braithwaite is credited with developing this concept which first appeared in his 1989 book Crime, Shame, and Reintegration. He refashions the practice of shaming such that it need not always be negative and destructive. Punishment and shame can serve legitimate functions by communicating social disapproval and forming normative expectations. A key difference between positive and negative practices of shaming is how they construct the identity of the offender. If punishment and shaming are used to stigmatize, to impose an identity as wrongdoer, and to lower the very status of the person in the community, then Braithwaite suggests it will be a self-fulfilling prophecy. On the other hand, if punishment and shaming are reintegrative – if the identity of the offender is regarded as good and the person’s status in the community is maintained – education and restoration are possible.

With this concept of reintegrative shaming in mind, we need not explain away all acts of punishment in order to make sense of a message of salvation. Punishment, by its mere existence, neither necessitates malice nor cruelty. An educative function is possible and often desirable. Thus, instead of focusing on the method of punishment or shaming, Braithwaite helpfully suggests we turn our gaze to the way the identity of the offender is being constructed in the process. Does the punishment stigmatize? Is the person reduced to mere sinner and evildoer? Are they beyond hope and recognition? Or, even in their sin, are they still beloved? Even in their betrayal and failure, are they worth redeeming?

This is the difference between punishment and condemnation. This is how we can begin to reconcile God’s response to a sinful people and God’s unwavering commitment to salvation. Even in the moments of our most horrific sins against one another, our identity and dignity remain. And this is the great power of ‘God sending his Son into the world’ as John’s Gospel proclaims. The Incarnation is the clearest evidence of all that our identity and dignity remain. Our humanity cannot be reduced to mere sin because it is a humanity that has a capacity for God. We need not explain away all punishment, shame, and suffering because we can have faith in a God who seeks to reintegrate, a God who is constantly affirming our identity as beloved sons and daughters.