The prophet Jeremiah’s style was so strident that he holds the distinction of having a word coined after him. A “jeremiad,” Wikipedia informs us, is a (long) text “in which the author bitterly laments the state of society and its morals in a serious tone of sustained invective, and always contains a prophecy of society’s imminent downfall.” In today’s first reading, we hear God encourage Jeremiah to stand strong, to speak all that needs to be spoken, despite those in power (kings and priests) raging against him.

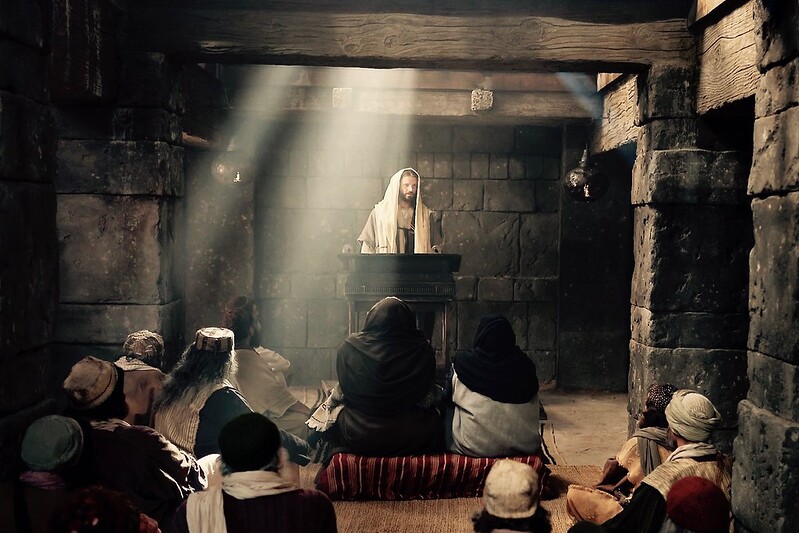

The odd thing about the Gospel passage with which the reading is paired is that Jesus has not just preached anything like a jeremiad. In last week’s Gospel, we heard him speak the encouraging words about the arrival of salvation and the various (positive) signs associated with it. Even this week, we hear that the initial reaction to Jesus’s words seems positive. This isn’t a lament over Jerusalem or even a John-the-Baptist style call to repentance in the desert.

It seems we must keep in mind the unique programmatic place this reading has in Luke’s Gospel, famously the Gospel written to the Gentiles. Sometimes, this reading focuses on the offhand remark about Jesus’s being “Joseph’s son” and is taken to suggest that people are trying to cut Jesus down to size by emphasizing his humble origins. But the real cause for offense here has to do with Jesus’s invocation of the miracles of Elijah and Elisha, the signs given to those outside Israel. As with many other famous Lukan stories, like the Good Samaritan, the Prodigal Son, and the visitation of Zacchaeus, the Gospel’s message of liberation and salvation ends up involving the “wrong” people.

God’s plan of salvation is for all, insiders and outsiders, Jews and Gentiles alike. The stories should not be a matter of simply creating a different privileged group, in which the “wrong” people become the “chosen” people. One would hope the history of Christian supersessionism would be enough to banish such flawed readings here. Instead of redescribing the plan, we should instead engage what the stories invite us to see, which is our reaction to the plan. In the Lukan stories noted above, the father of the prodigal and the Samaritan confronted with the wounded man have a distinctive, even emotional response – they are “filled with compassion.” It is interesting to contrast that response with the emotional reaction documented in today’s reading: fury.

The real choice the readings offer us today is about our response to God’s will to save all: are we (like that original sinner, Cain) filled with resentment, anger, and fear of missing out? Or do we recognize the suffering of others that is to be redeemed as itself the greatest sign of the love God exercises toward all of us? St. Paul’s famous hymn to love, in its full form in today’s second reading, is not first and foremost about marriage, but about the spiritual gifts we should seek. Above all, seek the love that sees the expansiveness of Gospel salvation as something joyful. Ditch the fury.