2 Samuel 7:1-5, 8b-12, 14a, 16

Psalm 89:2-5, 27, 29

Romans 16:25-27

Luke 1:26-38

In his classic book, The Politics of Jesus (which the evangelical magazine Christianity Today once listed as #5–right after works by C.S. Lewis, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Karl Barth, and J.R.R. Tolkien–among the top ten books of the twentieth century), John Howard Yoder focuses on Luke’s Gospel while taking issue “with the modern ethicists who have assumed that the only way to get from the gospel story to ethics, from Bethlehem to Rome or to Washington or Saigon, was to leave the story behind” (2nd edition, 12-13). Throughout the book, Yoder attempts to demonstrate that “the claims of Jesus are best understood as presenting to hearers and readers not the avoidance of political options, but one particular social-political-ethical option” that is “also normative for a contemporary Christian social ethic” (11).

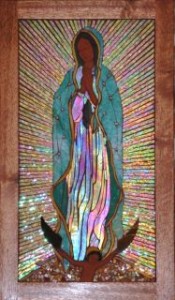

Yoder begins where the author of the Gospel of Luke begins: with the Annunciation and its echoes of the the song of Hannah (1 Samuel 2): “In the present testimony of the gospel we are being told that the one whose birth is now being announced is to be an agent of radical social change” (21-22). Just as God heard the cries and saw the humiliation of the enslaved Hebrews in Egypt centuries earlier, now God has, as Gustavo Gutierrez notes, “looked upon” the humiliating oppression of Mary and her people, this time under the occupation of the Roman empire (90). The intention of the author of this gospel is “clearly to say that the holy one, the wholly other, is not a distant God. God becomes flesh, one of us, in the womb of Mary” (91). Mary, after she consents, shall conceive and give birth to a son named after Joshua who led the Hebrew people into the promised land. He will inaugurate a new and never-ending “kingdom,” and the “political” wording here was intentional. As Yoder points out, today we tend to filter this language of the Annunciation wrongly as to be taken “spiritually” (22).

It should be noted, especially for readers today, that in first century Palestine, neither the Jews nor the Romans distinguished “politics” from “religion”–or “spirituality” for that matter. With few exceptions, back then people didn’t see themselves as having a religion separated from other aspects of their lives. Being religious, rather, meant being a part of (religare = “tied” or “bound together”) a people, a culture (note the root word here). Moreover, when God became human in the Incarnation, every aspect of Jesus–his teachings, his actions, indeed his entire life, including his death and resurrection–was redeeming for humankind. As the late Russell B. Connors, Jr. and Patrick McCormick put it in Character, Choices & Community: The Three Faces of Christian Ethics, “After the incarnation, then, it is not possible for Christians to accept any dualism that fails to attend to the holiness of our bodies, or any politics, economics or theology that disregards or ignores the embodied sufferings of the naked, the hungry, the sick or the imprisoned, or any social structure or system that oppresses, alienates or marginalizes these bodies. Everything about our human condition must now be taken seriously and must now be part of our loving response to God” (109).

But I want to get back to Mary, because as my Methodist friend Debra Dean Murphy has eloquently pointed out, the Fourth Sunday of Advent is “not about the baby” so much as about Mary testifying “to what Jesus’ life (and death) will mean, it has little to do with cradles and creches and Christmas angels, and everything to do with raw power and the vulnerable poor.” According to Luke Timothy Johnson, in his commentary on the Gospel of Luke, Mary “is among the most powerless people in her society: she is young in a world that values age; female in a world ruled by men; poor in a stratified economy. Furthermore, she has neither husband nor child to validate her existence. That she should have found ‘favor with God’ and be ‘highly gifted’ shows Luke’s understanding of God’s activity as surprising and often paradoxical, almost always reversing human expectations” (39). I think that Mary’s willingness to serve as a maternal “house” for the LORD to “dwell in” as a vulnerable baby (rather than a stone temple like King David wished to–and his son Solomon did–build, as mentioned in the first reading from 2 Samuel) moreover exemplifies Murphy’s important point here. Indeed, as Johnson notes, Mary represents the people of Israel (37), and I believe she embodies what the church as the people of God, individually and communally, should be and do.

In We Drink from Our Own Wells: The Spiritual Journey of a People, Gutierrez lifts up Mary as “a permanent model” for the church: “Daughter of a people that put all its trust in God, archetype of those who want to follow the path to the Father, she points out the way. The Magnificat, which Luke places on her lips, gives profound expression to what the practice of Latin American Christians is bringing to light once again in our day. The canticle of Mary combines a trusting self-surrender to God with a will to commitment and close association with God’s favorites: the lowly, the hungry” (127).

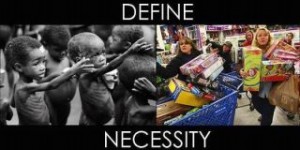

What would this Advent season look like today if we Christians were to put Mary back into “Merry” Christmas–er, I mean Advent? If we were to do so, I doubt we’d be comfortable with images such as this one, currently making the rounds on Facebook.