Fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time – On Being a Light of the World

Is: 58:7-10; Ps 112: 4-5, 6-7, 8-9; 1 Cor 2:1-5; Mt 5:13-16

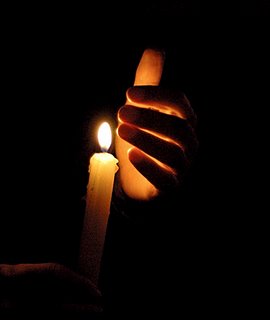

Any child who has been in a dark room, full of fear, can relate to the idea that light brings consolation and goodness. The hope brought by the dawn makes it easy to understand why Scripture speaks of God as light. In the book of the prophet Isaiah, the Messiah is a light: “The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light; upon those who lived in a land of gloom a light has shone” (Is 9:1). Similarly, the language of light appears at the very beginning of John’s Gospel:

What came to be through him was life, and this life was the light of the human race; the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. A man named John was sent from God. He came for testimony, to testify to the light, so that all might believe through him. He was not the light, but came to testify to the light. The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world (John 1:3b-9).

Light is a central motif of this Sunday’s readings as well, but in a different manner from the above. This week, the light we hear about is employed, not primarily to describe God, but to describe the faithful disciple. Psalm 112 succinctly declares: “The just man is a light in darkness to the upright.” In the first reading from Isaiah we are instructed about the nature of true fasting and learn that it involves giving bread to the hungry and giving shelter to the oppressed and homeless. The disciple’s light issues forth out of these works of mercy:

Then your light shall break forth like the dawn, and your wound shall quickly be healed;

your vindication shall go before you, and the glory of the LORD shall be your rear guard. . . .If you bestow your bread on the hungry and satisfy the afflicted;

then light shall rise for you in the darkness,

and the gloom shall become for you like midday. (Is 58:8,10)

It is difficult to get a precise sense of what is meant by this light. Is it a reference to the positive influence that a person may have on others? Is it an assertion about hopefulness and the ultimate victory of good over evil? Does it represent a person’s ability to better perceive the light of God? While it may be difficult (and possibly counterproductive) to arrive at a particular meaning of “light” here, the movement of the light seems significant. Note how it is “breaking forth” and “shining through” darkness. Darkness is the prior condition that is both interrupted and overwhelmed. The light of the disciple is not simply about shining brightly or amplifying visibility. Rather, it is about confronting a landscape of alienation and despair and radically transforming it. This is exactly what God has done for us through the Incarnation (thus Isaiah 9 and John 1 above). Through the Word taking flesh, the landscape of human sin and alienation was confronted and transformed. This is also what we are asked to do when we respond to the vulnerable and oppressed: confront the conditions of marginalization and despair and transform them. Thus, it makes good sense that the faithful disciple who acts with mercy will – in those very acts – has an intimate experience of God’s grace transforming her own despair and alienation. Isaiah’s talk of our wounds being healed and gloom becoming like midday seem to affirm this sense of the light. When we participate in the work of the light, we become light.

The Gospel of Matthew speaks of light as well. Jesus proclaims to his disciples:

You are the light of the world. A city set on a mountain cannot be hidden. Nor do they light a lamp and then put it under a bushel basket; it is set on a lampstand where it gives light to all in the house. Just so, your light must shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your heavenly Father. (Mt: 14-16)

While Isaiah articulated how a disciple’s light breaks forth, Jesus seems to be concerned with how – once luminous – a disciple might sabotage that light. Indeed, what would be the motivation for putting a lamp under a bushel basket? I have no doubt there are more, but three possible reasons (and temptations) come to mind.

First, there is the perfectionistic temptation. The disciple may dwell on his faults and fear that his light is not bright enough. The bushel basket helps to protect from humiliation until he can perfectly live out the word of God. He fails to understand that light is light. Whether dim or broken by shadows, it still transforms the darkness.

Second, there is the fear of inconsistency. The disciple may feel the weight of accumulating expectations on her and the burden of being seen as an exemplar. The bushel basket prevents others from assuming she will always be there and protects against the disappointment should she falter. She fails to understand that her own light is itself dependent on the light of God.

Third, there is the temptation of moral purity. The disciple is all too aware of his weakness for attention and affirmation. Knowing that the light has both its origin and its destination beyond him, he seeks the bushel basket as a refuge from his mixed motivations. He forgets that the light not only transforms the darkness of others but his own darkness as well.

This week, in contemplating what it means to be a light for the world, we are reminded of the many ways we can misunderstand and back down from this call. And, more importantly, we are reminded of why the image of light is so vital to who we are as disciples. Whether we are receiving it or attempting to offer it, the light confronts the darkness of alienation and despair and radically transforms it with love and hope.