In the desert of East Africa, between Somalia and Kenya lies the Dadaab Refugee Camp. Built to house 90,000 refugees, its population has currently swollen to about 400,000 people in and around the camp. The combination of drought, poverty, instability and violence in Somalia is leading about 1,500 people a day to cross into Kenya seeking refuge. ABC’s This Week with Christiane Amanpour highlighted this grwoing humanitarian crisis, which has been otherwise ignored by mainstream media outlets.

Lama Hasan details the heartbreaking stories of Dadaab’s most recent residents:

A mother of six was forced to decide today whether to leave behind her daughter, who is simply too sick to travel, in order to save the rest of her family. Suffering from malnutrition, her daughter isn’t strong enough to continue with their 30-day, 50-mile journey from Somalia into neighboring Kenya.

The mother, who was so traumatized that she couldn’t continue describing her ordeal or even give her name, had to leave her child by the side of the road to die.

Tamima Mohammed, who has travelled for 35 days with her seven children to get to Dadaab, is among the other refugees. Mohammed lies listless, covered in chicken pox, with no help in sight. She is still waiting to see a doctor. Her children are visibly malnourished, but Mohammed’s sack of grains is empty. She said she’ll have to beg her neighbors for something to eat.

Last week, High Commissioner for Refugees, António Guterres released a statement praising the Kenyan government’s decision to open the Ifo II camp extension to Dadaab. UNHCR reports note:

The alarm felt at Dadaab relates both to the escalating number of recent arrivals from Somalia, and the high death rates seen among young children in particular. With infants below five years in age, 3.2-fold and 3.8-fold increases in mortality are currently being seen at the Ifo and Hagadera camps compared with the prevailing rates a year ago. At the Dagahaley camp the increase has been six-fold.

At the end of the ABC news report, viewers were directed to a webpage which gave donation information for Unicef and Doctors without Borders, among others. For those who are able, these agencies along with Jesuit Refugee Services and Catholic Relief Services are doing exemplary work responding to the desperate need.

As Christians, however, we are called not only to provide aid but also to accompany the poor and vulnerable. It is a theology of accompaniement which is at the heart of the JRS mission around the world.

Our accompaniment affirms that God is present in human history, even in its most tragic episodes. We experience this presence. God does not abandon us. As pastoral workers, we focus on this vision, and are not side-tracked by political maneuverings and ethnic divisions, whether they are among the refugees or among the agencies and governments who decide their fate.

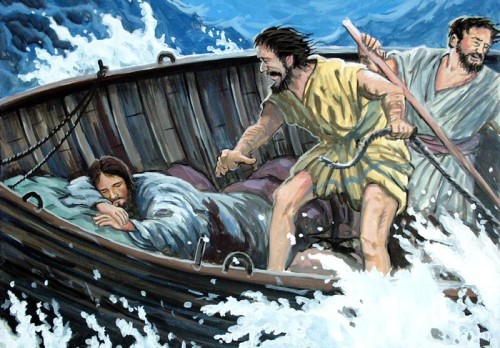

In Matthew 2:13-21 , reminds us that the Holy Family fled into Egypt as refugees.

When they had departed, behold, the angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, “Rise, take the child and his mother, flee to Egypt, and stay there until I tell you. Herod is going to search for the child to destroy him.” Joseph rose and took the child and his mother by night and departed for Egypt. He stayed there until the death of Herod, that what the Lord had said through the prophet might be fulfilled, “Out of Egypt I called my son.”

Often Catholics focus on the “holy innocents” who are murdered by Herod at the end of the story glossing over the Flight into Egypt for the remembrance of the innocent children lost. However, as Daniel Groody, CSC reminds us, the “Flight into Egypt” is crucial for Christian ethics response to the Refugee crisis and migration in general. In the “Flight into Egypt,” we are given a concrete image of God as a Refugee.

In the Incarnation, God, in Jesus, crosses the divide that exists between divine life and human life. In the Incarn

ation, God migrates to the human race, making his way into the far country of human discord and disorder, a place of division and dissension, a territory marked by death and the demeaning treatment of human beings. In Matthew’s account God not only takes on human flesh and migrates into our world but actually becomes a refugee when his family flees political persecution and escapes into Egypt (Matthew 2:13-15). Jesus assumes the human condition of the most vulnerable among us, undergoing hunger, thirst, rejection and injustice, walking the way of the cross, overcoming the forces of death that threaten human life. He enters into the broken territory of human experience and offers his own wounds in solidarity with those who are in pain. The Jesus story opens up for many migrants a reason to hope, especially in what often seems like a hopeless predicament.

What it means to accompany the refugees in Dadaab is easier to envision if you are an aid worker with Jesuit Refugee Services on the ground. It is much more difficult to think about how we, in the United States, can accompany the refugees in East Africa. Yet, as Christians, that is what we are called to do – to see in them the face of Jesus Christ, of God the Refugee and walk with those people and God.

Here are simply a few ways I think we, as Christians in the United States, can respond to God as Refugee among us. (this is by no means an extensive or exhaustive list.) First, in giving aid, we must internally do so in solidarity and with a recognition that more is expected of us (and not out of pity, condescension or superiority). Second, are we united with the people of Dadaab in prayer (and knowledge – news reports of refugee camps are uncomfortable and upsetting but it is our responsibility to be informed)? Third, do we see and extend the hand of friendship to refugees and displaced persons in our own communities? And, in a time of budget cuts – are we speaking up for those without a voice in a refugee camp dependent upon international aid for food and medicine supplies? That this is a situation of grave injustice and a massive violation of human dignity is incontrovertible, the question now is will we respond?

Meghan, thanks for this post! I’ve been following the news for the past few weeks and have been surprised that there has not been more coverage. BBC and NPR have had daily stories, but I will watch the ABC coverage you mention in the post.

It is so difficult to imagine the trauma of the refugees from where I sit. It can be a real barrier to the theology of accompaniment when my personal experience is so very different. Investigative reporting, ethnography, and our many online social networks can give us a glimpse of someone else’s life experience, but as you say this takes time and often leaves one with the unsatisfying feeling of powerlessness in the face of such complex and heartbreaking problems.

The complexity of this story is what really challenges me. This is not just a “natural” disaster, although that is one part of it. Global climate change is real and the drought is significant. But postcolonial scholars in East Africa have been trying to draw attention for some time to the problems of unequal land use (an inheritance of the colonial context), wide scale deforestation (related to both industry and poverty) and water scarcity. Those problems would be hard enough for any country to address, but the ethnic tensions in Kenya and the political vacuum in Somalia (where the transitional government has limited control in the face of warlords) makes this even more difficult. And in terms of foreign aid, the timing couldn’t be worse. The U.S. military is often the first to respond in humanitarian disasters, and I’m sure that they are involved in this somehow, but a wide-scale intervention is not likely given the memories of our Clinton-era “nation-building” and the ongoing involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan. Not to mention the fiscal crisis. And yet we know that Somalia is a haven for terrorism (I’m thinking of Al-Shabaab), and these refugees are not only poor, sick, and hungry, but also victims of a failed state. In that kind of context, and given the real problem of corruption in Kenya and Somalia, it is difficult to get food and medical aid into the right hands. This complexity highlights the need for a multifaceted response. So while personal donations, prayer, and hospitality are all important, I think the advocacy piece is really critical.

Emily,

Thanks for your comment!

I could not agree more – advocacy is KEY. but often seems so difficult to try and figure out the right advocacy….although finding people like Prendergast on Sudan/Darfur issues where you get a sense of trusting their analysis helps.

I was just so sickened by the realization that the ABC story was the first US tv station to air a report …..but I don’t know what the “right” set of answers are with regards to advocacy in this situation – as you note, it is so complex. But it seems somehow we must find a way to get food and medicine there – and advocating for that with our government seems the first step…cause its easy for the govt. to cut foreign programs unless its viewed by the public as a epidemic disaster.