This is the eleventh post in our Conscience at the Polls series.

So many have made this election into a debate about abortion. While authors in this series have argued that abortion is one among many life issues that voters must consider, the fact that it keeps coming up tells us that we have more work to do in reflecting on this important issue and the formation of faithful consciences. While abortion rates have been on the decline for a number of (contested) reasons, when 18% of pregnancies in the US (excluding miscarriages) end in abortion, one can see why people of faith are concerned (though they may not all share the same concerns or have the same priorities in addressing them). I’ve written elsewhere about why I think it is important to speak about abortion in such a way that we avoid shaming women in the pews; 24% of patients in 2014 identified as Catholic so at all times one should realize that when Catholics debate abortion, we do so as a community that includes women healing from abortion. Whatever you make of the issue, yesterday’s lectionary readings remind us of the absolute necessity of compassion to women in our approach.

This post will explain official church teaching on abortion and also show why official church teachings on abortion do not in themselves provide a simple answer for how one should “vote faithfully.”

What does the church teach about abortion?

The church teaches that a direct abortion is illicit because “the human being is to be respected and treated as a person from the moment of conception” (EV, 60); Pope John Paul II wrote in Evangelium Vitae (1995) that procured abortion is an “unspeakable crime” and “murder” (58). Direct abortion is when the agent freely chooses to terminate a pregnancy with the direct intent to kill unborn life. Pope John Paul II also explained that responsibility for upholding a culture of life does not only fall on pregnant women but also on the father of the unborn child, the extended family, friends, doctors and nurses, legislators, and those who spread an attitude of sexual permissiveness in a society (59). In Amoris Laetitia, Pope Francis wrote that “it matters little whether this new life is convenient for you, whether it has features that please you, or whether it fits into your plans or aspirations” (AL, 170). The popes often praise women for their sacrificial self-giving (see, for example, Mulieris Dignitatem) and for their unique role within the family, especially when they accept their role as mothers in alignment with magisterial presentation of gender norms in which women are understood, by nature, to be nurturing, loving, obedient, and selfless.

What guidelines exist for Catholic hospitals?

Every day, more than 1 in 7 patients in the U.S. is cared for in a Catholic hospital. According to the Catholic Health Association, the Catholic health ministry is the largest group of nonprofit health care providers in the nation, with over 600 hospitals and over 1,600 long term care and other health facilities in all 50 states. While Catholic teaching forbids direct abortions, in Catholic medical ethics, an “indirect abortion” refers to a legitimate medical procedure that may lead to the death of an unborn child. The Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services are the guidelines for Catholic health care delivery from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. With regard to abortion, some of those guidelines state:

Ethical and Religious Directives, 45-47.

45. Abortion (that is, the directly intended termination of pregnancy before viability or the directly intended destruction of a viable fetus) is never permitted. Every procedure whose whole immediate effect is the termination of pregnancy before viability is an abortion, which, in its moral context, includes the interval between conception and implantation of the embryo. Catholic health care institutions are not to provide abortion services, even based upon the principle of material cooperation. In this context, Catholic health care institutions need to be concerned about the danger of scandal in any association with abortion providers.

46. Catholic health care providers should be ready to offer compassionate physical, psychological, moral, and spiritual care to those persons who have suffered from the trauma of abortion.

47. Operations, treatments, and medications that have as their direct purpose the cure of a proportionately serious pathological condition of a pregnant woman are permitted when they cannot be safely postponed until the unborn child is viable, even if they will result in the death of the unborn child.

So, in authoritative Catholic teachings, it is morally impermissible to obtain a direct abortion, and Catholic hospitals are forbidden from providing abortion services.

Must Catholics support the criminalization of abortion?

Not necessarily. Even if Catholics agree that abortion is morally wrong, that does not mean that Catholics (as citizens or as politicians) share the same political strategies for reducing abortion rates. There is no single Catholic solution to this policy dilemma. Some will continue to seek to overturn Roe v. Wade; others will seek a constitutional amendment declaring that fetal life deserves equal protection under US law; and others will advocate not for a legislative or judicial approach at all but rather a cultural conversion. In a recent op-ed for the Philadelphia Inquirer, theologians Thomas Groome and Richard Gaillardetz, both of Boston College, draw on Thomas Aquinas to explain that we cannot move easily from a moral claim opposed to abortion to a clear legal or legislative agenda:

Thomas Groome and Richard Gaillardetz, “Can Pro-Life Catholics Vote for Joe Biden? Pro/Con” Philadelphia Inquirer

The greatest Catholic theologian, Thomas Aquinas, taught that laws must reflect “the consensus of the governed” if they are to be effective. So, until the great majority of Americans oppose abortion, Catholics cannot impose our moral norms on the rest of society.

Groome and Gaillardetz are not alone in this view. While they identify as pro-life Catholics, they look around and see that we live in a society in which not all of our neighbors share our views. Mary C. Segers elaborates on this point in “In Defense of Religious Freedom”:

The conclusion seems inescapable that, in a pluralistic society, religiously derived and religiously justified moral convictions must be subject to the tests of rational argument and persuasiveness if they are to be universalized and made into public policy for all citizens. Moreover, prudent political judgments must be made in any attempt to have one’s values embodied as part of our public morality… The plain reality is that religious convictions may be articulated in the shaping of public policy, but no one will be persuaded by such convictions if they remain particularistic. We must all appeal to a common standard of reasonableness if we are to converse, persuade, and agree upon public policy. This is one of the requirements of living as citizens in a multicultural democracy.

-Mary C. Segers, “In Defense of Religious Freedom” in A Wall of Separation? (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1998), 99.

I have argued against a legislative approach and in favor of a model that seeks to transform our social structures so that women facing unplanned pregnancies feel empowered to bring their babies to term. I find it morally repugnant to use the law to coerce women into compulsory motherhood and instead think that it honors the human dignity of women when we attempt to persuade them as moral agents, drawing on the best of our tradition’s resources and our own witness of solidarity and accompaniment. I have become ambivalent about the term “pro-life,” which I used to use to describe myself until President Trump adopted the term for himself. In order to be very clear that I stand firmly opposed to his well documented sexism, racism, xenophobia, lying, and family separation policies, none of which merit the descriptor “pro-life,” I am reluctant to use that term for myself anymore. It is worth noting, as Segers does, that a bishop should not tell a faithful Catholic how to exercise their prudential judgment in the voting box. Segers writes:

While lay Catholics owe their religious leaders respectful consideration, they do not and cannot, as citizens in a democracy, abdicate their responsibility to make their own prudential political judgments about candidates and issues. Bishops and priests who ignore these political realities act to undermine principles of democratic governance and civic participation. In using the privileges and trappings of religious authority to influence political decision making, clergy fail to show proper respect for the political autonomy of their parishioners, who are, after all, their political equals in a liberal democracy.

Segers, 104.

Groome and Gaillardetz realize their limits as well. Writing as theologians, they put it this way:

It is not for us to dictate the conscience-based decisions of other Catholics. But speaking from the depths of our own souls, not only may we vote for Biden-Harris, but believe we must do so. To do otherwise would be contrary to our consciences — our sin.

Groome and Gaillardetz

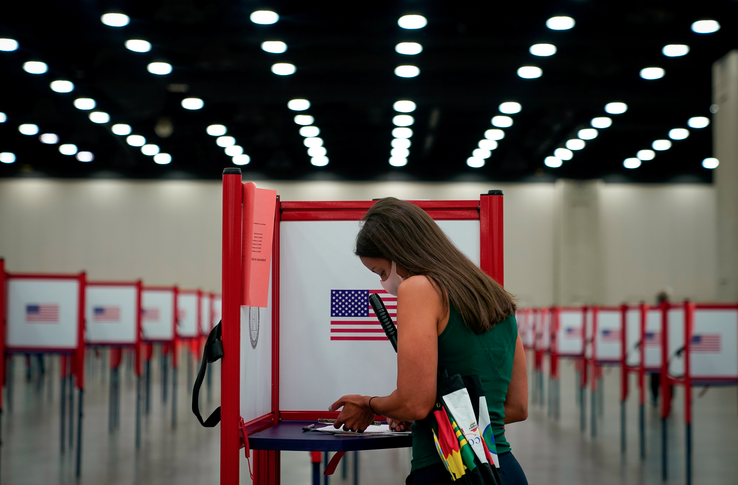

On the issue of abortion, as with so many others, there are faithful Catholics in both parties and some who have opted out of the US party system. Each must follow her conscience, which is to say, each voter must make the best possible decision within the recognized constraints, all the while recognizing that our work together as citizens of this country is about a lot more than what we do one day every four years.