This morning my colleague Julie Hanlon Rubio posted an excellent blog on Paul Ryan and Poverty. I agree with her 5 points and find them helpful. In the face of poverty, responding to the immediate need is necessary as is structural change (employment, education, affordable housing, etc). This is why the USCCB emphasizes charity and justice as the “two feet of love in action.” One of the key elements of Julie’s post is the recognition that we are all deeply embedded in personal, familial, social, and cultural realities.Social programs and family life both need to be strengthened to empower those for whom “life is a hill.” We need a broader and deeper understanding of what constitutes family – so that the inter-generational reality of strong families is captured within our vision of “the answer.” Thus, as she notes, strengthening families of single mothers and single fathers can only be done by listening and engaging them.

We seem to have hit a point where we are on a merry-go-round and do not ever seem to move beyond that. Personally, I find it particularly difficult to keep blogging on the same issues – because actual data doesn’t seem to make a difference in the public debate. And yet, I want to make a strong case that the loud and constant debunking of Ryan’s claims about poverty and poor persons is absolutely necessary for the common good. Personal responsibility, as self-determination, agency, and empowered participation is absolutely crucial. Personal responsibility as an ideological weapon is an attack on the human dignity of persons in and near poverty. Part of why I find treating it as an ideological battle cry incredibly dangerous is in doing so one misses the assumption of one’s own moral superiority that appears latent within.

So why am I stuck on the need to debunk? Because the assumptions of privilege and the re-shaping of the landscape from that position of privilege strikes me as particularly dangerous to the very project of finding common ground to fight poverty.

Almost 3 years ago, I wrote “The Overwhelming Desire to Connect Wealth and Holiness: The Primordial Social Sin?” in which I argued that:

Linked with the sin of pride, 21st century upper- and upper-middle class Americans find it very difficult to view their power, privilege, status and wealth as largely an accident of birth and circumstance. I do make choices, and I am responsible for my choices. However, my choices are also highly socially conditioned and one can only choose from the range of available options. The powerful image of the American Dream (when divorced from the necessary social structures it presumes) and the myth of the rugged individual pulling himself up by his bootstraps fuel this Americanized version of material wealth as a sign of God’s favor and become a dangerous weapon with which to blame the poor for their inability to get out of poverty.

Latent within the statements of the poor as lazy or simply as not working hard enough, in my opinion, is a strong desire to see oneself as morally superior and favored by God. Another aspect that is increasingly skewing this debate is these growing cases of “affluenza” wherein those who are privileged somehow “have it harder.” This week that case was made quite starkly by Gwynth Paltrow, who in an interview said:

“It’s much harder for me,” she said. “I feel like I set it up in a way that makes it difficult because … for me, like if I miss a school run, they are like, ‘Where were you?’ I don’t like to be the lead so I don’t (have) to work every day, you know, I have little things that I like and obviously I want it to be good and challenging and interesting, and be with good people and that kind of thing.”

“I think it’s different when you have an office job, because it’s routine and, you know, you can do all the stuff in the morning and then you come home in the evening,” said the polarizing Paltrow. “When you’re shooting a movie, they’re like, ‘We need you to go to Wisconsin for two weeks,’ and then you work 14 hours a day and that part of it is very difficult. I think to have a regular job and be a mom is not as, of course there are challenges, but it’s not like being on set.”

The overwhelming negative reaction was almost immediate, including many “Open letters from working moms.” Yet, I don’t want to reduce Paltrow’s clear lack of perspective as just another aspect of the “mommy wars.” I think it is representative of something much deeper – a sense that how hard one works and one’s moral character is connected to material success. That Paltrow cannot recognize her privilege is deeply troubling but even more troubling is the connection between poverty and assumed laziness. It is predicated on this idea that if one works or works hard enough – one wouldn’t be poor. It should be obvious that the single-mother working 14 hour days at minimum wage to make ends meet day in day out, with no job protection in the event of illness has it much more difficult than an A-list movie actress. Yet, this understanding of “hard work” is latent in almost every single attack on SNAP and other anti-poverty programs.

From the perspective of Christian ethics, this is precisely the “self-righteousness” Jesus rebukes throughout the Gospels. Why is it so difficult in America for us to see our neighbor as equally human? As our brother and sister? As even just our “neighbor”? Within the Christian community, I think part of the problem lies in the popular “WWJD?” or What Would Jesus Do? Such a configuration immediately places me in the ROLE of God the outcome of which makes it easier to “pat myself on the back” for all of my good works. It is much more difficult to focus instead on SEEING CHRIST in the other person. Visiting a homeless shelter in Rome last May, Pope Francis highlighted that

“To love God and neighbor is not something abstract, but profoundly concrete: it means seeing in every person the face of the Lord to be served, to serve him concretely. And you are, dear brothers and sisters, the face of Jesus.”

As I have previously argued, the key question is not “would Jesus cut the SNAP budget?” (although I do think the answer is obviously no…) but the real question for us is “Would You Deny Jesus Food Stamps?”

Jesus is not like the poor. Jesus is the poor. Jesus is not like the unemployed father who cannot find work and for whom food stamps are the only thing preventing his children from going to bed hungry. Christ is not like single mother working two low-paying part time jobs surviving only through access to housing and child care subsidies. Jesus Christ is that father. Jesus Christ is that mother.

Are you prepared when confronted with systemic food insecurity and hunger to determine who is and is not “worthy” of having their basic needs met? Standards for federal programs are one thing, this constant assumption of mistrust and suspicion of the poor as the starting point for evaluating poverty programs is quite another. It begs the question – what are we overlooking in ourselves when assuming the other is “undeserving.”

The need to debunk is not simply a matter of defending means tested poverty programs, it is also a check against pride and self-righteousness. This is why I find the invocation of work, hard work, and laziness so problematic. I am a tenure track college professor – this places me firmly within the middle class and with significant control over my day to day life. As those who know me can attest, I work hard to be sure – but it is sheer arrogance and pride to use that to make any evaluation or comparison to the reality of “hard work” of those workers upon whom my lifestyle depends.

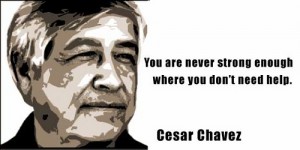

Cesar Chavez: An American Hero opened this past weekend chronicling the Catholic labor leader, the birth of the UFW, and the ongoing fight for farm workers rights. Farm workers engage in backbreaking work, often in unsafe working conditions with little or no security or protection. The fight for their basic rights as workers did not end with the successful grape and lettuce boycotts of the 1960s and 70s. It continues today – we still live in a world where someone who picks our food often cannot afford to feed their family.

Structural change is needed. Cultural change is needed. Personal participation is needed. But perhaps a good place to start is changing the “entitled culture” of the privileged more than obsessing over a potential “entitlement culture” of those living in or near poverty.

Structural change is needed. Cultural change is needed. Personal participation is needed. But perhaps a good place to start is changing the “entitled culture” of the privileged more than obsessing over a potential “entitlement culture” of those living in or near poverty.

*edited to fix typos

Meghan,

Thanks for this generous response. I definitely see your point. It’s important to correct false perceptions about why some people are poor and others are rich, especially when those who are privileged tend to assume they have earned all they have. Privileged people can be particularly blind to their own tendency to view the world through the lens of their experience, and it could be dangerous to discourage debunking when it strives to correct false perceptions and misuses of “personal responsibility.” This is part of why I find Pope Francis’ comments on personal change on the part of the privileged (I can find no similar comments about the poor) so helpful. Questioning entitlement at the top is definitely the place to start.

But I worry when the two sides talk past each other, especially when potential for common ground is there. For instance, in the Mother Jones/National Review exchange, the two authors went back and forth about single fathers, neither yielding much ground. Couldn’t we agree to something like this: “Single fathers are more involved in their kids’ lives than most people think. However, they their investment compared to that of married fathers is small. What more do we need to learn? Along with advocating for a higher wages, how can community programs reach out to single fathers?”

My fear is that without conversations like these, liberals are stuck arguing for structural changes that may or may not come to pass and conservatives are stuck telling people to change their lives on their own. We could do a lot more together in the space between these two spheres. At least, it’s worth a try.

Julie,

I agree that I think Pope Francis is providing an excellent witness for how we should be approaching these things – in addition to the very strong urges to conversion and “looking in the mirror” (through his use of parables and how often he uses Cain/Abel) it is the WAY he uses PLACE to deliver his message that is so instructive – at the homeless shelter, at Jesuit Refugee Center, AT Lampedusa, etc. I also appreciate and share your desire to have conversations that can achieve progress for persons in poverty – my own frustration is two-fold. First, I am tired of arguing against ideological myths about poverty and social programs and second, I think we are in a deep battle for who we are as a nation – basically all of the hard won gains of the civil rights movement, labor movement, and new deal seem at stake (never mind future gains) and this terrifies me.